|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Kalamis |

|

| |

Kalamis

Kalamis (Κάλαμις; Latin, Calamis) is the name of one or more Greek artists thought to have been working in the 5th - 4th centuries BC.

A Greek artist named Kalamis was mentioned by a number of ancient authors of the Roman period, including by Pliny the Elder, Pausanias, Quintilian, Cicero, Lucian, Dionysios of Halicarnassus, Sextus Propertius and Ovid, the two latter particularly noted the excellence of his horses.

However, as is often the case, it is not clear whether they were referring to the same person or a number of artists with the same name. It is thought that the authors, writing centuries after the people and events they discussed, often confused the names of artists who had made famous artworks, some known only from even more ancient books, others reported as still existing somewhere in the Roman Empire. In some cases writers may have "conflated" certain personalities, that is they assumed that mentions of a number of different persons in various sources referred to a single person.

Modern scholars believe that these references point to at least two, perhaps three different artists, who are discussed below:

Kalamis 1

a sculptor of the 5th century BC

Kalamis 2

a sculptor of the 4th century BC

Kalamis 3

an artist working in silver, perhaps Kalamis 2 |

|

|

| |

| Kalamis |

Kalamis 1

sculptor of the 5th century BC |

|

|

|

Working in Boeotia, Olympia and Athens around 470-420 BC; a contemporary of Pheidias

Perhaps from Athens or Boeotia

Kalamis is thought to have worked around 470-420 BC, calculated from the death of Hieron I, the tyrant of Syracuse, in 467 BC, and the end of the plague in Athens in 426 BC [1]. He is therefore thought to have been a sculptor of the Severe style of the early Classical period.

His place of birth is unknown, but Boeotia has been suggested because of the mentions of works he made there. The suggestion was first made by Franz Studniczka in 1907, and repeated by a number of scholars since. It has been refuted, notably by William M. Calder III, who convincingly argued that Kalamis could just as well have been an Athenian. [2]

Kalamis made bronze, marble and chryselephantine (gold and ivory) sculptures, and his statues of horses were particularly admired.

"Lysippus' glory is to carve with the stamp of life: Calamis', I consider is in his perfect horses."

Sextus Propertius (circa 50-15 BC), The Love Elegies, Book III.9:1-60 He asks for Maecenas' favour, translated by A. S. Kline. At Poetry in Translation.

Propertius' comparison of Kalamis with Lysippos (circa 390-305 BC) may indicate that he was referring to a sculptor of the 4th century BC, perhaps Kalamis 2, but not necessarily.

Kalamis was mentioned in the same verse as Pheidias and Myron in a poem by Ovid.

Arthur Leslie Wheeler (editor), P. Ovidius Naso, Ex Ponto, Book 4, poem 1. Harvard University Press, 1939. At Perseus Digital Library.

Roman authors such as Cicero (Marcus Tullius Cicero, 106-43 BC) and Quintilian (Marcus Fabius Quintilianus, circa 35-100 AD) saw an evolution in technique and aesthetic quality from the "stiff" and "crude" works of Greek artists such as Kanachos of Sikyon (the Elder), Kallon and Hegesias (see Hegias), in the late 6th - early 5th century, becoming "softer" and more lifelike in the time of Kalamis and Myron, then approaching a zenith of finesse and "ideal grace" in the works of Polykleitos. Quintilian added Pheidias, Alkamenes, Lysippos and Praxiteles to the evolutionary curve.

"But who that has seen the statues of the moderns, will not perceive in a moment, that the figures of Canachus are too stiff and formal, to resemble life? Those of Calamis, though evidently harsh, are somewhat softer. Even the statues of Myron are not sufficiently alive; and yet you would not hesitate to pronounce them beautiful. But those of Polycletes are much finer, and, in my mind, completely finished. The case is the same in painting; for in the works of Zeuxis, Polygnotus, Timanthes, and several other masters who confined themselves to the use of four colours, we commend the air and the symmetry of their figures; but in Aetion, Nicomachus, Protogenes, and Apelles, every thing is finished to perfection."

Cicero, Brutus, a History of Famous Orators, section 70. At attalus.org.

"The same differences exist between sculptors. The art of Callon and Hegesias is somewhat rude and recalls the Etruscans, but the work of Calamis has already begun to be less stiff, while Myron's statues show a greater softness of form than had been achieved by the artists just mentioned.

Polyclitus surpassed all others for care and grace, but although the majority of critics account him as the greatest of sculptors, to avoid making him faultless they express the opinion that his work is lacking in grandeur. For while he gave the human form an ideal grace, he is thought to have been less successful in representing the dignity of the gods. He is further alleged to have shrunk from representing persons of maturer years, and to have ventured on nothing more difficult than a smooth and beardless face.

But the qualities lacking in Polyclitus are allowed to have been possessed by Phidias and Alcamenes. On the other hand, Phidias is regarded as more gifted in his representation of gods than of men, and indeed for chryselephantine statues he is without a peer, as he would in truth be, even if he had produced nothing in this material beyond his Minerva at Athens and his Jupiter at Olympia in Elis, whose beauty is such that it is said to have added something even to the awe with which the god was already regarded: so perfectly did the majesty of the work give the impression of godhead.

Lysippus and Praxiteles are asserted to be supreme as regards faithfulness to nature. For Demetrius is blamed for carrying realism too far, and is less concerned about the beauty than the truth of his work."

Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria, Book 12, chapter 10, sections 7-9. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Works by Kalamis 1 mentioned by ancient authors |

|

|

Marble Apollo in the Servilian Gardens, Rome

Pliny the Elder believed that a statue of Apollo, probably of marble, which stood in the Servilian Gardens in Rome, was made by Kalamis, and that he was also the maker of silver cups he had mentioned earlier (see Kalamis 3). It is not known if Pliny was referring to Kalamis 1, Kalamis 2 or some other artist of this name. It is possible that he conflated one or more sculptors named Kalamis with a silversmith of the same name.

"I find it stated, also, that the Apollo by Calamis, the chaser already mentioned, the Pugilists by Dercylides, and the statue of Callisthenes the historian, by Amphistratus, all of them now in the Gardens of Servilius, are works highly esteemed."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Thebes, Boeotia

According to Pausanias, Kalamis made a statue of Zeus Ammon at Thebes in Boeotia for the poet Pindar (Πίνδαρος, circa 522-443 BC). The association of Kalamis with Pindar indicates a sculptor of the 5th century BC, although this has been refuted [see note 2].

"Not far away is a temple of Ammon; the image, a work of Calamis, was dedicated by Pindar, who also sent to the Ammonians of Libya a hymn to Ammon. This hymn I found still carved on a triangular slab by the side of the altar dedicated to Ammon by Ptolemy the son of Lagus." [3]

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 16, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

Tanagra, Boeotia

He made the marble cult statue of Dionysus for the temple of Dionysus at Tanagra, Boeotia.

"In the temple of Dionysus the image too is worth seeing, being of Parian marble and a work of Calamis."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 20, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Also at Tanagra he made a statue of Hermes Kriophoros (Ram-bearer), later depicted on Roman coins of the city.

"Beside the sanctuary of Dionysus at Tanagra are three temples, one of Themis, another of Aphrodite, and the third of Apollo; with Apollo are joined Artemis and Leto. There are sanctuaries of Hermes Ram-bearer and of Hermes called Champion. They account for the former surname by a story that Hermes averted a pestilence from the city by carrying a ram round the walls; to commemorate this Calamis made an image of Hermes carrying a ram upon his shoulders. Whichever of the youths is judged to be the most handsome goes round the walls at the feast of Hermes, carrying a lamb on his shoulders."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 22, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

That Kalamis was said to have made the statue to commemorate the end of the "pestilence" outbreak at Tanagra suggests he made it shortly after the event. The idea of Hermes carrying a ram is much older, and bronze figures of Hermes Kriophoros made in the Peloponnese date to the mid 6th century BC. Pausanias noted a statue of Hermes Kriophoros in Olympia, made by Kalamis' contemporary Onatas (working around 480-450 BC) and dedicated by the people of Pheneos, Arcadia.

Olympia

At Olympia he made bronze statues of two race horses with seated boy jockeys for Deinomenes (Δεινομένης), the son Hieron I (Ἱέρων Α΄), the tyrant of Syracuse 478-467 BC. Hieron had won victories at the Olympic Games, once in the four-horse race and twice in the horse race, but died before he could fulfill his vow to dedicate offerings to Olympian Zeus as thanks. "And so Deinomenes his son paid the debt for his father" (Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 42, sections 8-10). Kalamis probably collaborated on the commission with Onatas of Aegina (working circa 480-450 BC), who made the bronze statue of Hieron's chariot (see Onatas of Aegina).

"Hard by is a bronze chariot with a man mounted upon it; race-horses, one on each side, stand beside the chariot, and on the horses are seated boys. They are memorials of Olympic victories won by Hiero the son of Deinomenes, who was tyrant of Syracuse after his brother Gelo. But the offerings were not sent by Hiero; it was Hiero's son Deinomenes who gave them to the god, Onatas the Aeginetan who made the chariot, and Calamis who made the horses on either side and the boys on them."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 12, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias believed that a bronze statue group of boys with outstretched arms, dedicated at Olympia by the city of Akragas (Ἀκράγας; today, Agrigento), southern Sicily, was made by Kalamis.

"At the headland of Sicily that looks towards Libya and the south, called Pachynum, there stands the city Motye, inhabited by Libyans and Phoenicians [Carthaginians]. Against these foreigners of Motye war was waged by the Agrigentines, who, having taken from them plunder and spoils, dedicated at Olympia the bronze boys, who are stretching out their right hands in an attitude of prayer to the god. They are placed on the wall of the Altis, and I conjectured that the artist was Calamis, a conjecture in accordance with the tradition about them."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 25, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

Also at Olympia he saw a statue by Kalamis of Nike as "Wingless Victory" (Νίκη Ἄπτερος, Nike Apteros), after the cult statue in the Temple of Athena Nike on the Athens Acropolis.

"Near to the greater offerings of Micythus, which were made by the Argive Glaucus, stands an image of Athena with a helmet on her head and clad in an aegis. Nicodamus of Maenalus was the artist, but it was dedicated by the Eleans. Beside the Athena has been set up a Victory. The Mantineans dedicated it, but they do not mention the war in the inscription. Calamis is said to have made it without wings in imitation of the wooden image at Athens called Wingless Victory."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 26, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

Sikyon, northen Peloponnese

Pausanias described a chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of the healing god Asklepios by Kalamis in the sanctuary of Asklepios at Sikyon. The figure was beardless, and although he was usually shown with a beard, a marble statuette from Epidauros shows him as a beardless youth.

"When you have entered you see the god, a beardless figure of gold and ivory made by Calamis. He holds a staff in one hand, and a cone of the cultivated pine in the other. The Sicyonians say that the god was carried to them from Epidaurus on a carriage drawn by two mules, that he was in the likeness of a serpent, and that he was brought by Nicagora of Sicyon, the mother of Agasicles and the wife of Echetimus."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 10, section 3. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

|

Athens

Pausanias also tells us that Kalamis made a statue of Apollo Alexikakos (Απολλων Ἀλεξίκακος, the Averter of Evil) which stood in front of the small Ionic temple of Apollo Patroos in the Athenian Agora:

"These pictures were painted for the Athenians by Euphranor, and he also wrought the Apollo surnamed Patrous [Paternal] in the temple hard by. And in front of the temple is one Apollo made by Leochares; the other Apollo, called Averter of evil, was made by Calamis. They say that the god received this name because by an oracle from Delphi he stayed the pestilence which afflicted the Athenians at the time of the Peloponnesian War."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 3, section 3. At Perseus Digital Library.

It stood next to another Apollo by Leochares (working around 370-320 BC). The statue of the god inside the temple was by Euphranor (working around 390-325 BC). Although the temple itself was built in the second half of the 4th century, the reference to Apollo ending the plague in Athens (429 or 426 BC) during the Peloponnesian War [see note 1] suggests an earlier date for the statue, and thus by this Kalamis rather than his later namesake. However, the statue need not necessarily have been made immediately after these events.

(A statue of Herakles Alexikakos by Ageladas was set up around the same time in the Attic deme of Melite. See Ageladas of Argos.)

More than 20 extant Roman period statues of the "Omphalos Apollo" type are thought to be copies of a bronze statue possibly made by Kalamis around 460-450 BC. The type is named after a 2nd century AD marble statue found in 1862 at the Theatre of Dionysos, Athens (see photo, right), which was originally associated with a base in the shape of an omphalos found near it. The identification has since been challenged, and it has been suggested that the figure represents Apollo Alexikakos, and even that it may have been a work of Onatas. On the other hand, the Kassel type Apollo statues are also thought to be copies of the Apollo Alexikakos.

The torso of another "Omphalos Apollo", found in 1744 in the River Tiber near Rome, and dated to around 130-138 AD (Altes Museum, Berlin, Inv. No. Sk 510, see Antinous), was restored with the head of another statue to resemble the "Capitoline Antinous", a statue of Hermes believed at the time to be a portrait of Antinous. Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline Museums, Rome, Inv. No. MC 741. |

|

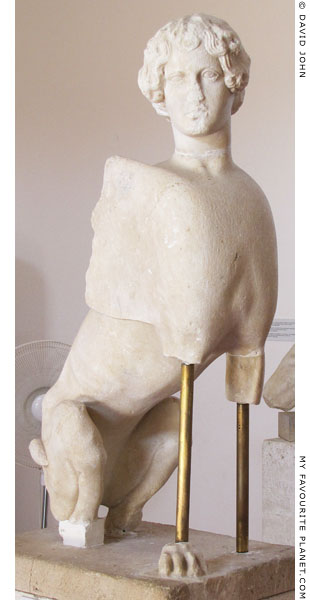

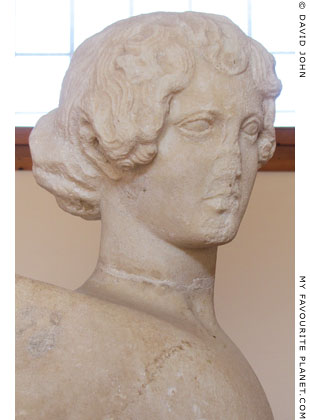

Marble statue of Apollo, known

as the "Omphalos Apollo" after

an omphalos-shaped base with

which it was originally associated.

Pentelic marble. 2nd century AD

copy of a bronze original of the

Severe Style, around 460-450 BC,

possibly by Kalamis 1.

Found at the Theatre of Dionysos,

Athens in 1862. Height 176 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 45. |

|

| |

|

|

|

A marble sphinx statue from the temple of Apollo in Aegina.

Around 460 BC, early Classical period.

Some scholars have seen similarities in this sphinx to the "Omphalos Apollo"

and have attributed it to Kalamis. Others believe it is probably a local work.

Aegina Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1383. |

|

|

Aphrodite and/or Sosandra on the Acropolis, Athens

In front of the Propylaia of the Athens Acropolis, Pausanias reported a statue of Aphrodite said to be by Kalamis and to have been dedicated by the wealthy Athenian statesman, soldier and diplomat Kallias (Καλλίας, circa 500-432 BC), brother-in-law of Kimon and a supporter of Pericles. It has been estimated that the statue may have been made around around 465 BC.

"It is one of the sayings of the Greeks that there were Seven Sages. Amongst these they reckon the Lesbian tyrant and Periander, son of Cypselus. Yet Pisistratus and his son Hippias were more humane than Periander and sager in the arts both of war and peace, until the death of Hipparchus exasperated Hippias. Amongst the objects on which Hippias vented his fury was a woman named Leaena [Λέαινα, Lioness].

The story has never before been put on record, but is commonly believed at Athens. He tortured Leaena to death, knowing that she was Aristogiton's mistress, and supposing that she could not possibly be ignorant of the plot. As a recompense, when the tyranny of the Pisistratids was put down, the Athenians set up a bronze lioness in memory of the woman. Beside it is an image of Aphrodite, which they say was an offering of Callias and a work of Calamis." [4]

Pausanias's Description of Greece, Volume 1 (of 6), Book I, Chapter 23, sections 1-2, page 32. Translated with a commentary by James George Frazer. Macmillan and Co., London, 1898. At the Internet Archive.

The Syrian essayist Lucian of Samosata (Λουκιανός ὁ Σαμοσατεύς, circa 125-180 AD) mentioned a statue of "Sosandra" (Σωσάνδρα, Saviour of Men) by Kalamis on the Athens Acropolis when imagining an ideal female portrait made up of parts from famous works by sculptors, painters and poets. This fantasy construction takes place in a witty dialogue between Lycinus (probably Lucian himself) and Polystratus, thought to have been written in 162/163 AD in praise of Panthea, the mistress of Emperor Lucius Verus.

"Lycinus: I forbear to ask whether in the course of your many visits to the Acropolis you ever observed the Sosandra of Calamis.

Polystratus: Frequently.

Lycinus: That is really enough for my purpose. But I should just like to know what you consider to be Phidias's best work.

Polystratus: Can you ask? — The Lemnian Athene, which bears the artist's own signature; oh, and of course the Amazon leaning on her spear.

Lycinus: I approve your judgement. We shall have no need of other artists: I am now to cull from each of these its own peculiar beauty, and combine all in a single portrait.

Polystratus: And how are you going to do that?

Lycinus: It is quite simple. All we have to do is to hand over our several types to Reason, whose care it must be to unite them in the most harmonious fashion, with due regard to the consistency, as to the variety, of the result.

Polystratus: To be sure; let Reason take her materials and begin. What will she make of it, I wonder? Will she contrive to put all these different types together without their clashing?

Lycinus: Well, look; she is at work already. Observe her procedure. She begins with our Cnidian importation, from which she takes only the head; with the rest she is not concerned, as the statue is nude.

The hair, the forehead, the exquisite eyebrows, she will keep as Praxiteles has rendered them; the eyes, too, those soft, yet bright-glancing eyes, she leaves unaltered. But the cheeks and the front of the face are taken from the 'Garden' Goddess; and so are the lines of the hands, the shapely wrists, the delicately-tapering fingers.

Phidias and the Lemnian Athene will give the outline of the face, and the well-proportioned nose, and lend new softness to the cheeks; and the same artist may shape her neck and closed lips, to resemble those of his Amazon.

Calamis adorns her with Sosandra's modesty, Sosandra's grave half-smile; the decent seemly dress is Sosandra's too, save that the head must not be veiled. For her stature, let it be that of Cnidian Aphrodite; once more we have recourse to Praxiteles. What think you, Polystratus? Is it a lovely portrait?

Polystratus: Assuredly it will be, when it is perfected. At present, my paragon of sculptors, one element of loveliness has escaped your comprehensive grasp.

Lycinus: What is that?

Polystratus: A most important one. You will agree with me that colour and tone have a good deal to do with beauty? that black should be black, white be white, and red play its blushing part? It looks to me as if the most important thing of all were still lacking.

Lycinus: Well, how shall we manage? Call in the painters, perhaps, selecting those who were noted for their skill in mixing and laying on their colours?

Be it so: we will have Polygnotus, Euphranor of course, Apelles and Aetion; they can divide the work between them. Euphranor shall colour the hair like his Hera's; Polygnotus the comely brow and faintly blushing cheek, after his Cassandra in the Assembly-room at Delphi.

Polygnotus shall also paint her robe, of the finest texture, part duly gathered in, but most of it floating in the breeze. For the flesh-tints, which must be neither too pale nor too high-coloured, Apelles shall copy his own Campaspe.

And lastly, Aetion shall give her Roxana's lips. Nay, we can do better: have we not Homer, best of painters, though a Euphranor and an Apelles be present? Let him colour all like the limbs of Menelaus, which he says were 'ivory tinged with red'. He too shall paint her calm 'ox-eyes', and the Theban poet shall help him to give them their 'violet' hue.

Homer shall add her smile, her white arms, her rosy finger-tips, and so complete the resemblance to golden Aphrodite, to whom he has compared Brises' daughter with far less reason.

So far we may trust our sculptors and painters and poets: but for her crowning glory, for the grace — nay, the choir of Graces and Loves that encircle her — who shall portray them?

Polystratus: This was no earthly vision, Lycinus; surely she must have dropped from the clouds."

Lucian, A portrait study (Greek, Εἰκόνες; Latin, Imagines). In: In: The works of Lucian of Samosata, Volume 3 (of 4), translated by H. W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler (following the text of Jacobitz, Teubner, 1901). Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1905. At Project Gutenberg.

Also at: A Portrait-Study. In: The Works of Lucian of Samosata. The same edition at ebooks at the University of Adelaide. |

|

|

| |

Some modern scholars believe that Pausanias' Aphrodite and Lucian's Sosandra were the same statue, which has been named "Aphrodite Sosandra". A type of marble statue, of which there are more than thirty examples (see photo, right), has been identified with this work. They all depict a standing woman draped in a himation (long woollen cloak), part of which covers the top and back of her head like a cowl. Her hair is parted in the middle and tied back so that it falls diagonally to either side of her forehead in waves. Her face, solemn and austere, has been sculpted in a way which has been associated with the Severe style of early Classical Greek sculpture.

There have been many objections to this theory, including that Sosandra is otherwise unknown as an epiphet for Aphrodite, and appears to be an unlikely name for such a deceitful deity. It has also been suggested that the "Sosandra" may have depicted Hera, Hestia, Demeter, a priestess of Athena Polias or Aglauros, or was even a portrait of Elpenike (Ελπινίκη), the wife of Kallias and half-sister of the statesman Kimon. The sculptures have also been referred to as "Europa" and "Amelung's Goddess".

The base of a marble herm of this type, discovered in 1777 near Civitavecchia, and now in the Vatican (see drawing, below right) is inscribed ΑCΠΑCΙΑ (= ΑΣΠΑΣΙΑ, Aspasia). This has lead to speculation that the type may portray the influential Aspasia of Miletus (circa 470-400 BC), the consort (or second wife) of Pericles, or that "Sosandra" may have been copied for Aspasia, and further copied during the Roman period. It is so far the only known sculpture with such an inscription, and many scholars have doubted its authenticity, pointing also to problems of reconciling the style of the sculpture with the time of Aspasia's life, as well as the fact that no statue of Aspasia is mentioned by ancient authors. Wealthy Romans had a preoccupation with acquiring portraits of famous historical personalities, and there are many examples of dubious labelling of statues and busts from ancient collections.

Sala delle Muse, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums.

Inv. No. 272.

Marble. Height 170 cm.

Inscription on front of stele: MVN. PIT. SEXTI. P. M

Found in 1777 at Torre della Chiarrucia (Castrum Novum) near Civitavecchia (80 km northwest of Rome). Thought to be a Roman copy of the first half of the 2nd century AD after an original of the 4th century BC.

Statues and reliefs of women draped and "veiled" in cloaks were common in antiquity, most often on funeral monuments showing the subject as the deceased or as a widow ( see photo, below right). However, men and women were also depicted in this manner as priests, and some deities are also shown hooded (see, for example, the "Demeter of Knidos" and the "Demeter Cherchel" type statues).

Two inscribed marble statue bases found in Athens have been associated with Kallias and Kalamis.

The first is part of a statue base of Pentelic marble, found in 1869 southeast of the Propylaia on the Acropolis. Four dowel holes in the top indicate that it supported a standing figure with feet close together. Dated to around 480-470 BC, it is inscribed with a dedication by "Kallias, son of Hipponikos", but no artist's signature has been found. It was previously believed to be the base for the statue of Aphrodite by Kalamis. However, it may have supported a statue of Kallias himself, set up after his victories in the Olympic Games. Pausanias mentioned that there was a bronze statue of Kallias in the Athens Agora. [5]

Καλλίας ℎιππονίκο ἀνέθ|εκ[ε]ν.

Kallias, son of Hipponikos, dedicated this.

Inscription IG I³ 835 (IG I² 607; Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 111) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Height 30 cm, length 64 cm, width 55 cm.

The second is a fragment of Pentelic marble, found on the lower North Slope of the Acropolis, south of the Agora, on 24 November 1937. It is inscribed with a dedication by Kallias and the signature of Kalamis, and from the letter forms it has been dated to the mid 5th century BC.

[Καλ]λίας

[ἀνέ]θηκε.

[Κάλ]αμις

[ἐπόε].

Kallias dedicated this. Kalamis made it.

Inscription IG I³ 876 (Antony E. Raubitschek, Dedications from the Athenian Akropolis [DAA], No. 136; Hesperia 12 (1943), page 18, No. 3) at The Packard Humanities Institute.

Height 17.5 cm, length 16.3 cm, width 24 cm.

This has also been suggested as the base of Kalamis' statue of Aphrodite. From the various theories, a hypothetical scenario emerges. Around 450 BC Kallias commisioned Kalamis to make a statue of Aphrodite. She may have been chosen due to the recent Athenian military victory at Cyprus, the birthplace of the goddess. At this time the area of the Propylaia (built 437-432 BC) was probably still in ruins or part of the vast building site on the Acropolis, and the statue may have been set up in the sanctuary of Aphrodite, west of the gateway.

It may have been moved to where Pausanias saw it following the building of the monumental stairway up to the Propylaia in the 1st century AD (see Athens Acropolis page 10). The original base may have been removed at the time of the move, which may explain why Pausanias did not see the original inscription and wrote "which they say was an offering of Callias and a work of Calamis". The question of the identity of "Sosandra" and her possible relationship to the Aphrodite statue remains unanswered.

Other extant statues considered

possibly to be works of Kalamis

"The Artemision Bronze", also referred to as "the God from the Sea", a 209 cm high bronze statue, thought to depict either Zeus or Poseidon (see below). Found in an ancient shipwreck off the coast of Cape Artemision, northern Euboea. Dated around 460 BC, a work of the Severe style of the early Classical period. Onatas, Myron, Kritios and Nesiotes have also been suggested. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 15161.

"The Charioteer of Delphi", also known as "Heniochos" (Ηνίοχος, the rein-holder), a 180 cm high bronze statue of a chariot driver, found in 1896 at the Sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi, and now in the Delphi Archaeological Museum. Dated variously to around 478-470 BC, it is a work of the Severe style of the early Classical period. It has been compared with the bronze Piraeus Apollo, and is thought to have been cast in Athens. Pythagoras of Samos has also been suggested as the sculptor. An inscription on the statue's limestone base states that it was dedicated to Apollo by Polyzalos, the tyrant of Gela, Sicily (brother of Hieron), following his victory in a chariot race in the Pythian Games. |

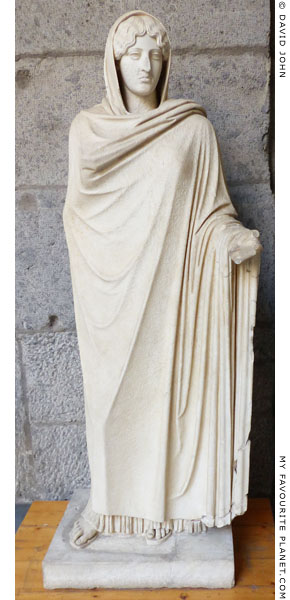

One of the finest examples of the

"Aphrodite Sosandra" (Saviour of Men)

type marble statue. Roman period,

thought to be a copy of a Greek original

by Kalamis, 460-450 BC.

Found in 1950 in the "Sector of Sosandra"

in the baths-theatre-nymphaeum complex

at Baiae, Bay of Naples. It was unfinished

and almost completely unpolished. It is

believed that a workshop at Baiae mass-

produced marble or bronze copies of

Greek sculptures for the Roman market

from original works. Height 183 cm.

National Archaeological Museum,

Naples. Inv. No. 153654. |

| |

Drawing of the marble herm bust in

the Vatican, showing the inscription

"ΑCΠΑCΙΑ" on the right side.

Height 170 cm.

Sala delle Muse, Museo Pio-Clementino,

Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 272. |

| |

Head of so-called "Aspasia".

"Roman, after a model from

around 470/460 BC."

Marble. Height 29.5 cm

(approximately lifesize).

Acquired by the old Royal Prussian

Collection in 1742. In 1799 in the

library of Friedrich II's Neue Palais,

Sanssouci, Potsdam. Transferred to

the Königliche Museum, Berlin in 1830.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 605. |

| |

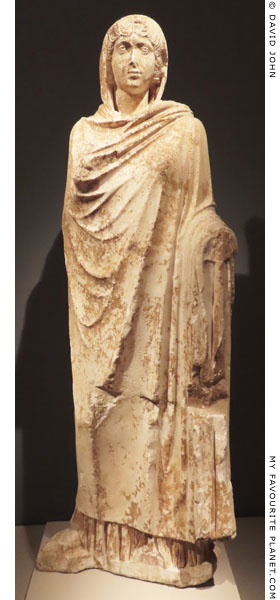

A marble statue of the "Aspasia" type.

Thought to be a funerary statue as a

portrait of a deceased woman.

180-190 AD. Allegedly from Aquino, Italy.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 1518. |

| |

| |

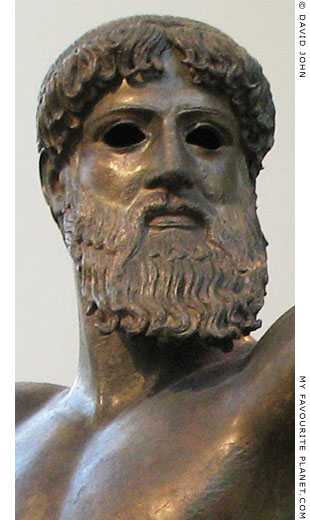

Detail of the "Artemision Bronze", a bronze statue of Zeus

hurling his thunderbolt or his brother Poseidon throwing a trident.

Around 460 BC. Larger than lifesize, height 209 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Room 13. Inv. No. 15161.

|

"The Artemision Bronze", also known as "the God from the Sea" and "the God of Cape Artemision", was found in 1926 (left arm) and 1928 (the rest of the sculpture) in an ancient shipwreck of the 2nd century BC or later off the coast of Cape Artemision, northern Euboea, Greece. Dated to around 460 BC, about the same time as a number of similar extant bronze figurines of Zeus, it is a rare work of Severe style which preceded the Classical style. It has been compared with the bronze "Charioteer of Delphi" made around the same time.

The idealized naked figure of the god is shown in a dynamic, athletic pose, with both arms stretched out horizontally, and about to hurl his terrible weapon. The eyes were inset, probably with glass and stone, and the brows and lips were inlaid with copper.

Incidentally, in the background of the photo above is part of a Roman period marble statue of the Minotaur, thought to be a copy of a work by Myron. |

|

The head of "the Artemision Bronze". |

|

| |

| Kalamis |

Kalamis 2

sculptor of the 4th century BC |

|

|

|

Pausanias named the sculptor Praxias (see Praxias and Androsthenes) as an Athenian and a pupil of Kalamis. Praxias sculpted the pediments of the Late Classical Temple of Apollo at Delphi, built around 350-330 BC, but died before its completion. Even if he was quite old at that time, it appears to have been too late for him to have been the pupil of Kalamis 1 above. Thus it is thought that his teacher was probably a second Kalamis, perhaps a grandson of Kalamis 1.

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 19, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Also, since Pliny the Elder mentioned that the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles (4th century BC) made a charioteer for a sculpture of a chariot by Kalamis ( see below), it has been assumed that this happened at the time or soon after Kalamis made it, although the work may have been made generations before, perhaps by Kalamis 1. If this Kalamis was a descendant of Kalamis 1, he had evidently inherited the latter's talent for sculpting horses, unless Pliny has confused two artists.

Just before Pausanias' mention of Praxias as a pupil of Kalamis, he described a statue of Hermione in Delphi by Kalamis. It is not clear whether he was referring to the same sculptor.

"There is here an offering of the Lacedaemonians, made by Calamis, depicting Hermione, daughter of Menelaus, who married Orestes, son of Agamemnon, having previously been wedded to Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 16, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Bronze chariots and Alkmena

Pliny the Elder wrote that Kalamis made bronze sculptures of chariots and praised his horses, and that Praxiteles made a charioteer for one of his chariots. He also mentioned that he made a statue of Alkmena (Ἀλκμήνη), the mother of Herakles:

"His [Praxiteles'] kindness of heart, too, is witnessed by another figure; for in a chariot and horses which had been executed by Calamis, he himself made the charioteer, in order that the artist, who excelled in the representation of horses, might not be considered deficient in the human figure. This last-mentioned artist has executed other chariots also, some with four horses, and some with two; and in his horses he is always unrivalled. But that it may not be supposed that he was so greatly inferior in his human figures, it is as well to remark that his Alcmena is equal to any that was ever produced."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Bronze Apollo from Apollonia Pontica

Strabo and Pliny the Elder mentioned a colossal bronze statue of Apollo, made for Apollonia Pontica (Ἀπολλωνία Ποντική; on modern Saint Ivan Island, Bulgaria) on the Black Sea. It was taken to Rome as war booty in 72 BC by Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus (circa 116 - soon after 56 BC), the proconsul of Macedonia, and set up in the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (also known as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus) on the Capitoline Hill. Strabo said that the statue was by Kalamis, and Pliny that the "Capitoline Apollo" was 30 cubits high (around 14 metres) and had cost 500 talents.

Again it is not certain when or by which Kalamis the statue was made. It seems more probable that such a colossal bronze was a product of the 4th rather than the 5th century BC. In the same chapter, Pliny also described another bronze colossus (of Zeus) by Lysippos (4th century BC) at Tarentum.

"... then, at one thousand three hundred stadia, to Apollonia, a colony of the Milesians. The greater part of Apollonia was founded on a certain isle, where there is a temple of Apollo, from which Marcus Lucullus carried off the colossal statue of Apollo, a work of Calamis, which he set up in the Capitolium."

Strabo, Geography, Book 6, chapter 7. At Perseus Digital Library.

"As to boldness of design, the examples are innumerable; for we see designed, statues of enormous bulk, known as colossal statues and equal to towers in size. Such, for instance, is the Apollo in the Capitol, which was brought by M. Lucullus from Apollonia, a city of Pontus, thirty cubits in height, and which cost five hundred talents."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 18. At Perseus Digital Library.

"On this side of the Ister [Danube] there is the single island of the Apolloniates, eighty miles from the Thracian Bosporus; it was from this place that M. Lucullus brought the Capitoline Apollo."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 4, chapter 27. At Perseus Digital Library. |

| |

The head of Apollo on a silver diobol

coin from Apollonia Pontica, Thrace.

Classical period, 425-375 BC.

Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam.

Inv. No. 13.071. |

| |

| |

Marble Apollo in the Servilian Gardens, Rome

Pliny believed that a statue of Apollo, probably of marble, which stood in the Servilian Gardens in Rome, was made by Kalamis, and that he was the artist who had made silver cups (see Kalamis 3). It is not known if he was referring to Kalamis 1, Kalamis 2 or some other artist of this name.

"I find it stated, also, that the Apollo by Calamis, the chaser already mentioned, the Pugilists by Dercylides, and the statue of Callisthenes the historian, by Amphistratus, all of them now in the Gardens of Servilius, are works highly esteemed."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

| Kalamis |

Kalamis 3

silversmith |

|

|

|

An artist in working silver. Dates and place of origin unknown.

Pliny the Elder mentioned a Kalamis as one of the most famous artists working in silver.

"It is a remarkable fact that the art of chasing gold should have conferred no celebrity upon any person, while that of embossing silver has rendered many illustrious. The greatest renown, however, has been acquired by Mentor..."

After mentioning the artists Acragas, Boethus and Mys, Pliny continued:

"Next to these in repute comes Calamis."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 33, chapter 55. At Perseus Digital Library.

It is not known if he was the 5th century BC Kalamis 1, the 4th century BC Kalamis 2 or another artist of this name. It is possible that he conflated one or more sculptors named Kalamis with a silversmith of the same name.

Pliny also wrote that the Roman period sculptor Zenodoros, the maker of the colossal statue of Nero in Rome (after which the Colosseum gained its name) in the mid 1st century AD, produced perfect copies of two silver cups made by Kalamis:

"At the time that he [Zenodoros] was working at the statue [of Hermes] for the Arverni [in Gaul], he copied for Dubius Avitus, the then governor of the province, two drinking-cups, chased by the hand of Calamis, which had been highly prized by Germanicus Caesar, and had been given by him to his preceptor Cassius Silanus, the uncle of Avitus; and this with such exactness, that they could scarcely be distinguished from the originals. The greater, then, the superiority of Zenodorus, the more certainly it may be concluded that the secret of fusing [precious] brass is lost." [6]

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 18. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pliny believed that this Kalamis was the artist who made a statue of Apollo, probably of marble, which stood in the Servilian Gardens in Rome (see Kalamis 2).

"I find it stated, also, that the Apollo by Calamis, the chaser already mentioned, the Pugilists by Dercylides, and the statue of Callisthenes the historian, by Amphistratus, all of them now in the Gardens of Servilius, are works highly esteemed."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

| Kalamis |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

|

1. The plague in Athens

There are several mentions of "plague" or "pestilence" in Greek cities by various ancient authors. The term was used to describe epidemics, but the exact diseases remain subjects of debate. The best known instances of the "plague" in Athens are the two outbreaks during the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), described in detail by Thucydides, which have been dated to 430/429 and 427/426 BC.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 2, chapter 47.

2. Kalamis 1 from Athens or Boeotia?

See:

William M. Calder III, Kalamis Atheniensis? In: Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies, Volume 15, No. 3, pages 271-277. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 1974. At Duke University.

Calder doubted the story related by Pausanias that Pindar had commissioned Kalamis to make the statue of Zeus Ammon at Thebes:

"I should query, therefore, the whole story (Paus. 9.16.1) of Pindar's hiring Kalamis to do a Zeus Ammon for him at Thebes. Rather a fiction by a Hellenistic biographer, based on Pythian 4.16 and the hymn to Ammon (fr.29 Turyn)."

3. The Ammonians of Libya

The "Ammonians of Libya" is presumably a reference to the sanctuary of Ammon (Amun) at Siwa, in the Western Desert of Egypt, which was visited by Alexander the Great in 332/331 BC.

4. Pausanias on Leaena and the Aphrodite by Kalamis

For some reason the English translation of this passage by W. H. S. Jones and H. A. Ormerod (Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, section 2) at Perseus Digital Library, omits the clause mentioning the statue of Aphrodite, so that it appears as if the work by Kalamis, dedicated by Kallias was the nearby statue of the lion. But the passage is intact in the Greek version:

"... παρὰ δὲ αὐτὴν ἄγαλμα Ἀφροδίτης, ὃ Καλλίου τέ φασιν ἀνάθημα εἶναι καὶ ἔργον Καλάμιδος."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 23, section 2. In Greek at Perseus Digital Library.

The story of Leaena was also related by Athenaeus and Pliny the Elder. Pliny mentioned the statue of the lioness when discussing sculptors in marble, and names the artist as Amphicrates, although this reading is considered doubtful and the names Iphicrates and Tisicrates have also been suggested.

See: Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 34, chapter 19. At Perseus Digital Library.

5. Pausanias on a bronze statue of Kallias in the Athens Agora

Unfortunately, Pausanias did not describe the statue or say who made it.

"After the statues of the eponymoi come statues of gods, Amphiaraus, and Eirene [Peace] carrying the boy Plutus [Plouton, Wealth]. Here stands a bronze figure of Lycurgus, son of Lycophron, and of Callias, who, as most of the Athenians say, brought about the peace between the Greeks and Artaxerxes, son of Xerxes [circa 448 BC]."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 8, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library.

6. Pliny on Zenodoros

In this translation his name is given erroneously as "Zenodotus", but in a number of Latin texts and most other sources it appears as Zenodorus. In Latin the name of Kalamis appears as "Calamidis".

See, for example:

Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, Book 34, chapter 18, section 45. In Latin at Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago. |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|