|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Antinous |

|

| |

Antinous

Antinous (Greek, Ἀντίνοος, Antinoos; circa 111 - 130 AD) was a "favourite" of Roman Emperor Hadrian (reigned 117-138 AD), born to a Greek family in the city of Claudiopolis (Κλαυδιόπολις; formerly Bithynion, Βιθύνιον; today Bolu, northwestern Turkey), Bythinia, northwestern Anatolia (Asia Minor), which at the time was a Roman province. The exact dates of his birth and death are unknown, but it is thought that he died before the end of October 130 AD at the age of 18-20. He met Emperor Hadrian when he was in his teens, perhaps during Hadrian's visit to Bythinia around 123/124 AD, and became his favourite and probably his lover (ἐρώμενος, eromenos, loved one).

He accompanied Hadrian on his tour of the empire, visiting Greece, Asia Minor and Egypt. After he drowned in the Nile at or near Hermopolis, Hadrian deified him, without consulting the Roman Senate, and erected many busts and statues of him at sanctuaries for his cult throughout the Roman Empire. He even founded (or refounded) a port on the east bank of the Nile, at the place where Antinous drowned, and named it Antinoopolis (Ἀντινόουπόλις). [1]

The location of Antinous' tomb is not known. Although it seems most likely that he was buried at Antinoopolis, it has also been suggested that Hadrian brought his body to the Antinoeion, the temple built in his honour at Hadrian's Villa in Tivoli, outside Rome, which was discovered in 1998. The question is further confused by an inscription on the Obelisk of Antinous (also known as the Pincian Obelisk), now in Rome, which appears to claim that it marks Antinous' grave (see below).

A number of scholars have speculated that Antinous' drowning in the Nile was not an accident and that he may have been sacrificed, or even sacrificed himself, to satisfy some religious requirement. Like Antinous, the Roman senator and historian Lucius Cassius Dio (Δίων Κάσσιος, circa 155-235 AD) was also from a Greek family in Bithynia. In his Roman History (Ῥωμαϊκὴ Ἱστορία, Historia Romana), written in Greek, he wrote that he believed Antinous was sacrificed due to Hadrian's superstitious nature.

"In Egypt also he [Hadrian] rebuilt the city named henceforth for Antinous [Antinoöpolis]. Antinous was from Bithynium, a city of Bithynia, which we also call Claudiopolis. He had been a favourite of the emperor and had died in Egypt, either by falling into the Nile, as Hadrian writes, or, as the truth is, by being offered in sacrifice. For Hadrian, as I have stated, was always very curious and employed divinations and incantations of all kinds.

Accordingly, he honoured Antinous, either because of his love for him or because the youth had voluntarily undertaken to die (it being necessary that a life should be surrendered freely for the accomplishment of the ends Hadrian had in view), by building a city on the spot where he had suffered this fate and naming it after him. And he also set up statues, or rather sacred images, of him, practically all over the world.

Finally, he declared that he had seen a star which he took to be that of Antinous, and gladly lent an ear to the fictitious tales woven by his associates to the effect that the star had really come into being from the spirit of Antinous and had then appeared for the first time. On this account, then, he became the object of some ridicule, and also because at the death of his sister Paulina he had not immediately paid her any honour"

Cassius Dio, Roman History, Epitome of Book 69,

chapter 11, sections 2-4. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius.

The sacrifice story may have been a product of rumours and gossip, or anti-Hadrian propaganda. It was also repeated in the anonymous Historia Augusta (Augustan History), a late Roman collection of biographies of Roman emperors and associated figures. The reliability of many of its passages is qustionable.

"During a journey on the Nile he lost Antinous, his favourite, and for this youth he wept like a woman. Concerning this incident there are varying rumours; for some claim that he had devoted himself to death for Hadrian, and others — what both his beauty and Hadrian's sensuality suggest. But however this may be, the Greeks deified him at Hadrian's request, and declared that oracles were given through his agency, but these, it is commonly asserted, were composed by Hadrian himself."

Historia Augusta, Life of Hadrian Part 1, chapter 14,

sections 5-7. At Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius.

A large number of depictions of Antinous have survived as statues, busts, reliefs, and on vessels, cameos and oil lamps, as well as on coins and medals issued by several cities across the Roman Empire. The handsome young man was often depicted in the guise of a Greek, Roman or Egyptian deity or mythological hero, including: Osiris, Apis or Osiris-Apis, Hermes, Hermes-Thoth, Horos-Harpokrates, Men, Dionysus, Dionysus-Osiris, Iacchos, Apollo, Asklepios, Poseidon, a river god, Herakles, Bellerophon, Androklos.

He was usually represented as a mythological figure with a particular significance for the people at the places where the sculptures were set up. At Ephesus, for example, he was depicted as Androklos, the legendary founder of the city (see photo below).

Hadrian was perhaps hoping for acceptance of the worship of Antinous by assimilation into local religious beliefs and practices. It is uncertain what the local people in various places around the empire thought of the imposition of the cult, or how popular it became or remained after Hadrian's death in 138 AD, although coins depicting Antinous were still being issued during the reign of Caracalla (198-217 AD), and it is known that there were still cult followers and statues standing until the prohibition of pagan religions by Emperor Theodosius I in 391 AD.

It may be that some were affronted by appropriation of their ancient cult images by the newcomer. However, during the reign of Hadrian the Roman Empire was at the height of its power and prosperity in a period of consolidation and construction, from which many profited, particularly the wealthy Romanized citizens. New gods had already been widely accepted, including Egyptian and syncretic deities such as Serapis, and worship of the deified emperors appears to have become the norm.

The wealthy Athenian Herodes Atticus, a younger contemporary of Hadrian who built a number of sanctuaries for Antinous, later established a similar cult for his young eromenos Polydeukes. |

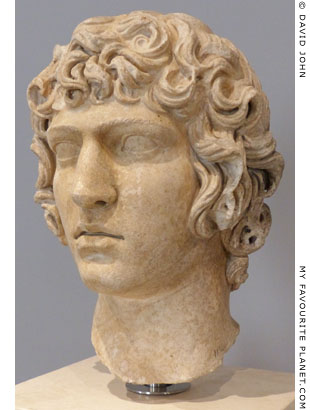

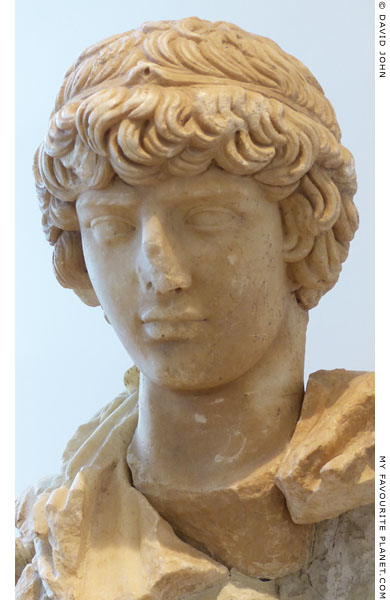

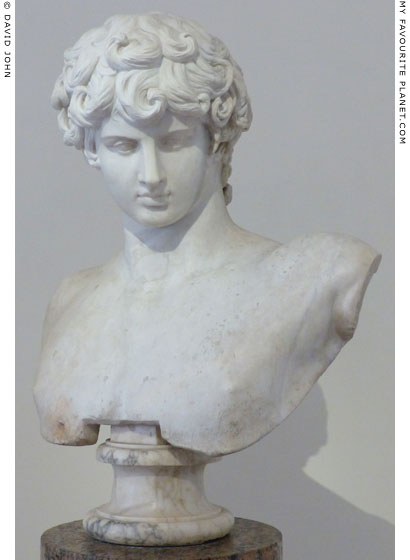

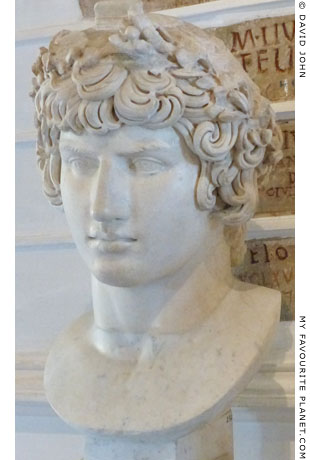

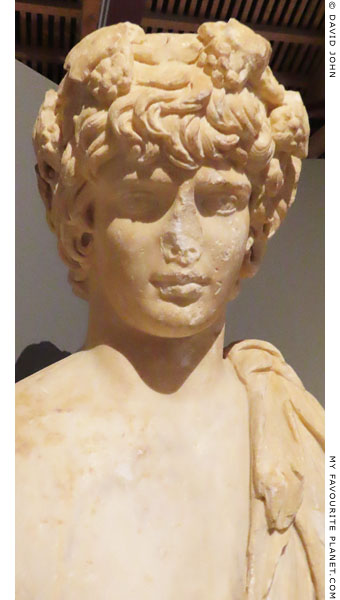

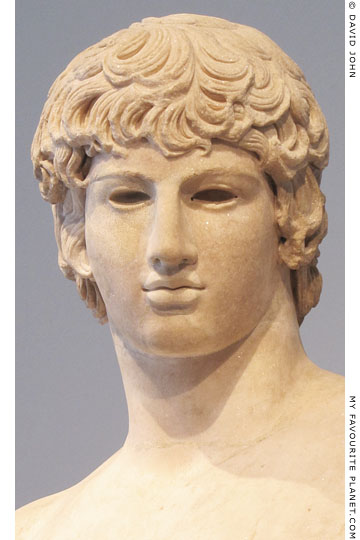

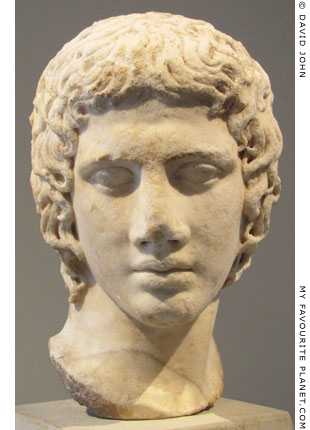

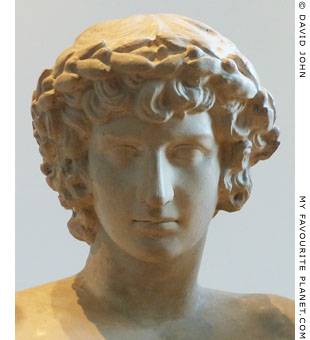

Marble portrait head of Antinous from

Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli. 130-138 AD.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme,

National Museum of Rome.

Inv. No. 1192. |

| |

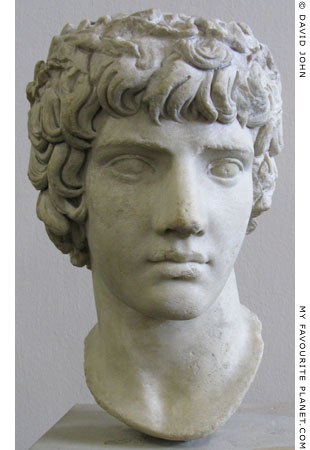

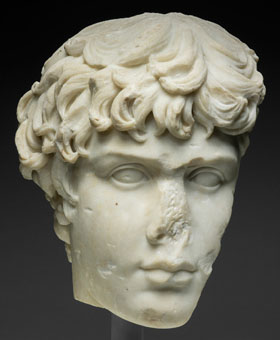

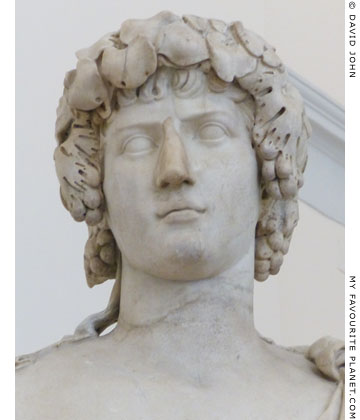

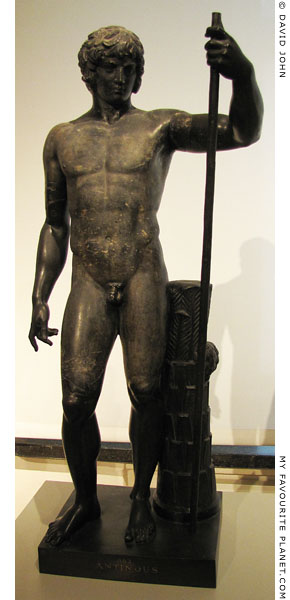

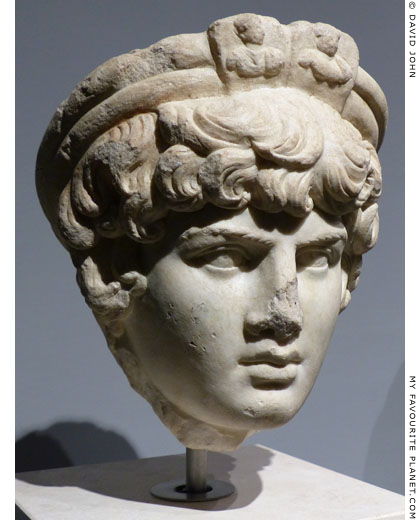

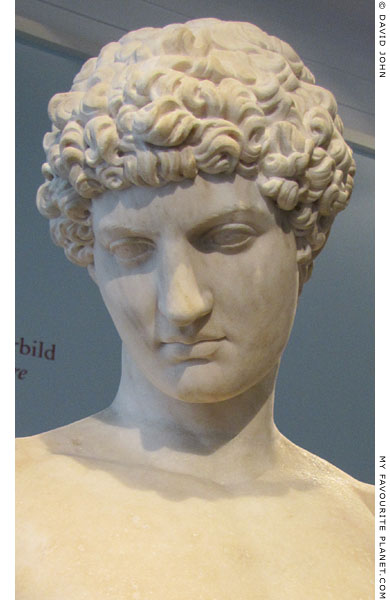

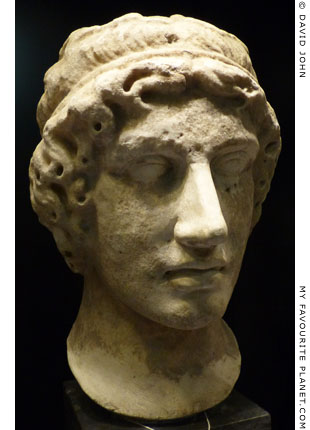

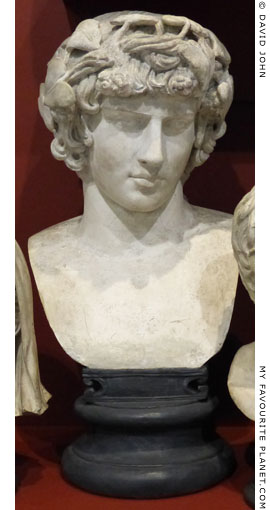

Marble head of Antinous wearing

a crown of myrtle. Around 130-138 AD.

Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 363.

Purchased in Cairo in 1878. |

| |

| |

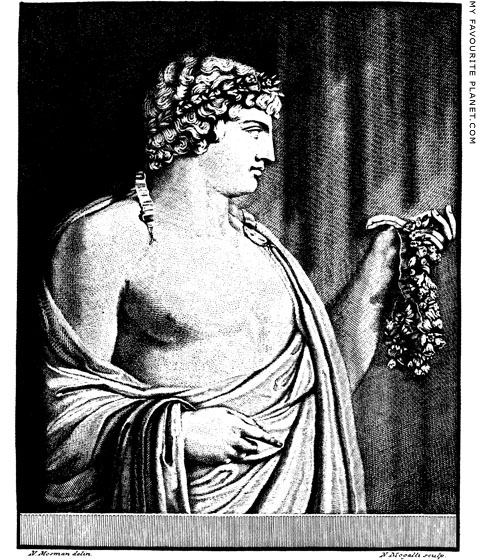

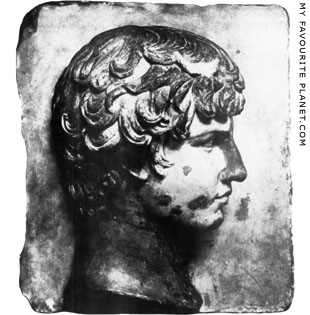

An engraving of the marble "Albani relief" depicting Antinous, perhaps

represented as Vertumnus, the Roman god of seasons, in the Villa Albani,

Rome. Published by the German art historian Winckelmann in 1767.

Drawing by Nikolaus Mosmann (circa 1727-1787), engraving

by Niccolò Mogalli. Height of relief 102 cm, width 77 cm.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), Monumenti antichi inediti spiegati

ed illustrati da Giovanni Winckelmann, Volume I (Unedited antique monuments,

described and illustrated by Giovanni Winckelmann). Rome, 1767. At Heidelberg

University Digital Library. Mondragone head, plate 179; Albani relief, plate 180. |

| |

The fragmented relief, made of white Luni (Carrara) marble, was discovered in 1735 at Hadrian's Villa in Tivoli and immediately acquired by Cardinal Alessandro Albani, after which it became known as the "Albani Relief". It still stands over a fireplace in the Villa Albani where the cardinal set it up in the 1760s, apart from a short hiatus 1798-1815 when it was in Paris, having been confiscated by Napoleon's troops.

Much of the Albani Collection was later sold off and the works are now dispersed among many collections and museums around the world (for example, the Capitoline Museums, Naples, Dresden and the Louvre). However, several works are still in the private collection of the villa which has belonged to the Torlonia family since 1866. Like many objects in the collection, the relief is not currently on display. Plans were set in motion in 2016 to finally exhibit the works from the Villa Albani-Torlonia, several of which have been kept in storage for many years.

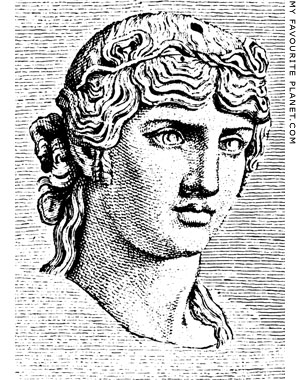

An engraving of the relief, after a drawing by the portrait painter Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787), was published in 1736. Winckelmann's praised the relief and the "Antinous Mondragone" head (image, right), which he called "the glory and crown of art in this age as well as in others" and "so immaculate that it appears to have come fresh out of the hands of the artist". Notably, the engraving of the relief in his Monumenti antichi inediti (Tavolo 180) is the only one in the book to be signed by an artist, and is of a much higher quality than the other printed illustrations (even if it does make Antinous look slightly obese). His publication of the relief led to its wider fame which was further spread by the sale of plaster casts, paintings and prints. Portraits of Antinous became fashionable as an ideal of youthful male beauty from the 18th century, and were eagerly sought after by collectors.

The relief was restored to show the figure holding a lotus garland in his left hand, although Winckelmann believed that he should be holding the reins of a horse. It has been suggested that the figure depicts Antinous as Vertumnus, the Roman god of seasons, plant growth, gardens and fruit trees (see also a relief of Antinous as Silvanus below). So few depictions of this god have survived that the identification remains doubtful. It has even been mooted that the work is a modern fake. |

|

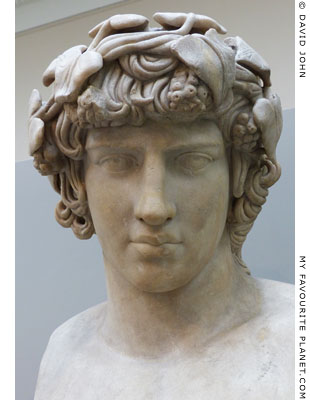

Engraving of the "Antinous Mondragone",

a colossal marble head of Antinous, from

Winckelmann's Monumenti antichi inediti

(Tavolo 179). Said to have been found

between 1713 and 1729 at Frascati, it

was displayed in the Villa Mondragone

there as part of the Borghese Collection.

Since 1808 in the Louvre.

Parian marble. Height 95 cm.

The top of the head, which may be from

a bust or statue, was originally decorated

with a lotus flower, uraeus (cobra) or pine

cone. Traces of bright red colour are still

visible, particularly in the hair. The eyes

were of metal, ivory or coloured stone.

Louvre Museum, Paris.

Inv. No. Ma 1205 (MR 412).

Purchased for Napoleon in 1807. |

|

| |

The Obelisk of Antinous (Obeliscus Antinoi), also known as the Pincian Obelisk

or Barberini Obelisk, now in the Viale dell'Obelisco, on the Pincian Hill, Rome.

Aswan pink granite. Present height 9.75 metres.

|

The obelisk is thought to have been commissioned by Emperor Hadrian as a monument to Antinous. The inscriptions in Egyptian hieroglyphs on all four sides of the shaft, perhaps translated from a text written by Hadrian himself, are considered among the most important primary sources concerning Antinous and his cult (see also the inscription from Lavinium below), although it contains no biographical information about him.

The original location of the obelisk is unknown, but it may have stood either in the Antinoeion at Hadrian's Villa in Tivoli or in the gardens of the Palatine Hill. According to another theory, it may have been brought to Rome from Egypt in the 3rd century AD, during the reign of Emperor Elagabalus (218-222 AD), who may have set it up in the Circus Varianus near the Porta Maggiore. Equally, it is uncertain whether the Egyptian hieroglyphs were inscribed in Egypt or Rome. The unusual orthography of the text has proved very difficult to translate and interpret, making it yet another subject of debate, and it has been suggested that the text was written or inaccurately copied by someone with a poor understanding of Egyptian sacred language.

The inscription on one side is in praise of Hadrian, and on the other three sides Antinous is described as a "beautiful youth", proclaimed as the new god Osiris-Antinoos, with details of his attributes, cult and daily offerings to him, and he is depicted before Thoth, Amun, and another deity. There is also a description of the city of Antinoopolis, inhabited by Greeks and Egyptians, and the colossal temple of Antinous there, built of limestone in a mix of Egyptian and Greek styles, surrounded by sphinxes and statues. A hippodrome in the city is also mentioned. A passage on the side thought to have been the south face appears to claim that Antinous is buried at the site of obelisk, apparently at the home of Hadrian:

"The blessed one who is in the afterlife and who lies in this sacred place which is found inside the gardens of the domain of the Prince in Rome." [2]

Even if the obelisk did stand in the Tivoli villa or the Palatine gardens, this claim is no proof that it marked the actual grave of Antinous: it may have been intended as a cenotaph (symbolic empty grave).

The obelisk was discovered in 1570 by the Saccoccia brothers, owners of the vineyard Vigna Saccoccia, outside the Porta Maggiore. It appears they intended to erect it, although it is uncertain whether they managed to do so. The plaque recording their find was affixed to a pier of the Aqua Claudia aqueduct (which became part of the Acqua Felice in 1585), about 360 metres east of the Aurelian wall, and can still be seen there.

Around 1633 it was purchased by Cardinal Francesco Barberini and moved to the garden of the Palazzo Barberini, but was never erected there. In 1773 Cornelia Barberini gave it to Pope Clement XIV and it was taken to the Cortile della Pigna (Court of the Pine Cone) in the Vatican. Again, plans to set it up in the Vatican gardens were never realized. Eventually, in 1822 Pope Pius VII commissioned the Italian architect and archaeologist Guiseppe Valadier (1762-1839) to restore the obelisk, which had become broken into three pieces, and it was erected at its present location in September of the same year.

Sources do not agree on the height of the obelisk: the entire monument, including the modern base and star on top, is either 17.26 or 17.9 metres tall, and the ancient obelisk itself 9.24, 9.25, 9.35 or 9.75 metres tall. Take our pick - or your tape measure. |

|

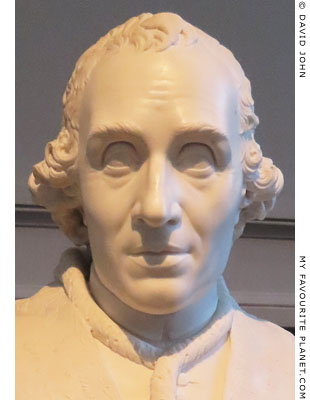

Marble bust of Pope Pius VII (1742-1823)

made in 1805 in the workshop of the

sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822).

H: 74,0 cm, B: 62,0 cm, T: 34,0 cm.

Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum, Dresden.

Inv. No. ZV 3154. Purhased in 1931 from

the art dealers Salomon, Dresden. |

|

| |

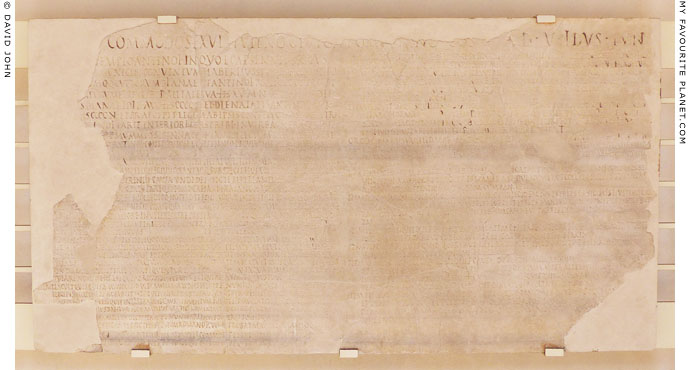

A marble slab with an inscription containing a statute of the collegium (association)

of worshippers of Diana and Antinous at the ancient city of Lanuvium (today Lanuvio),

in the Alban Hills, Latium, 32 kilometres southeast of Rome.

136 AD. Reconstructed from several fragments found in 1816 among the ruins

of ancient Lanuvium, on the Laviniense provincial road, near the Appian Way.

Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome.

Inv. No. 1031. Inscription CIL 14.2112.

|

The worshippers (cultores), members of the collegium, met at a newly built tetrastyle temple of Antinous six times a year, on the birthdays of Diana (Artemis), Antinous and four important local officials. The inscription is thought to have been set up on one of the walls in the temple.

The inscription has a single heading line across the length of the panel, below which is a column of thirty three lines on the left and a column of thirty two lines on the right. It begins with an account of the assembly of the college on 9th June 136 AD, during which L. Cesennius Rufus, patron of the municipium of Lavinium, donated 15,000 sesterces for the organization of religious feasts on the birthdays (dies natalis) of Diana, on 13th August, and Antinous (Natalis Antinoi), on 27th November. It also mentions that the college was founded for charitable and funerary purposes on 1st January 133 AD, and that the Senate authorized prayers for Emperor Hadrian and his family. The statute details rules concerning subscriptions, fines for defaulters, exemptions and privileges for certain members, and prodedures for members' funerals, including those for slaves and suicides. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

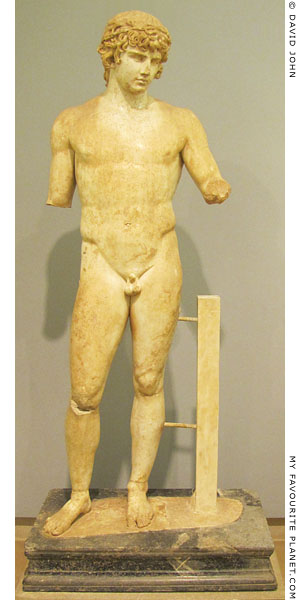

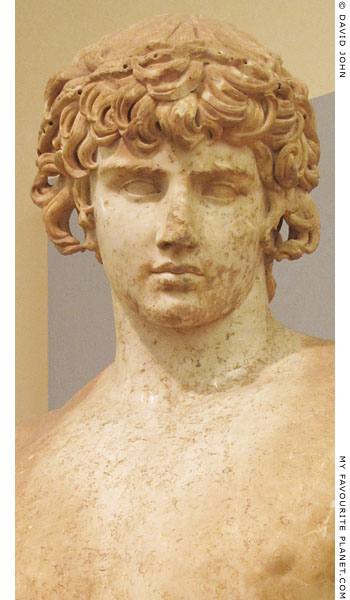

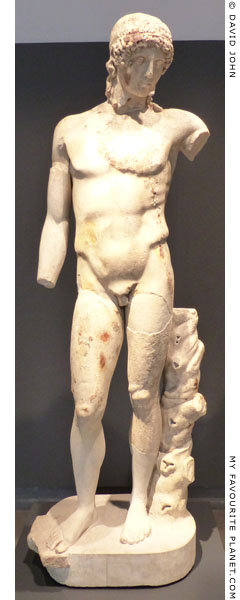

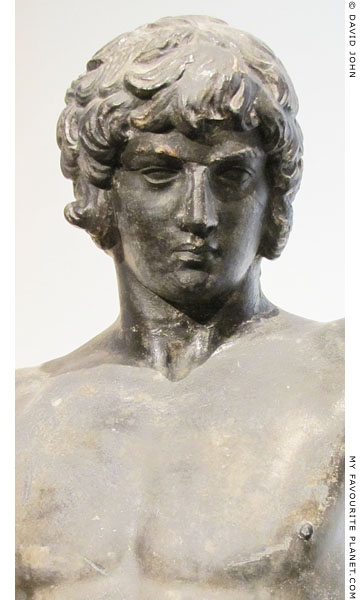

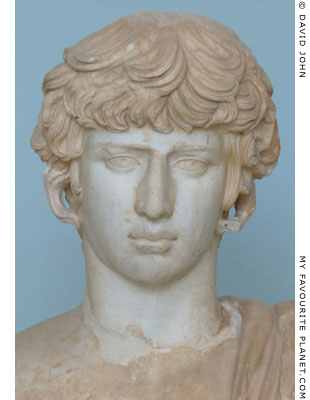

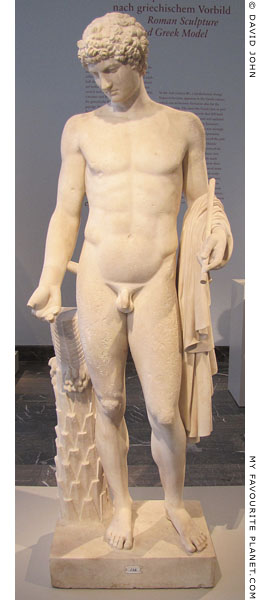

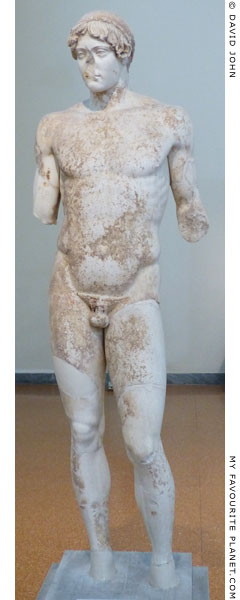

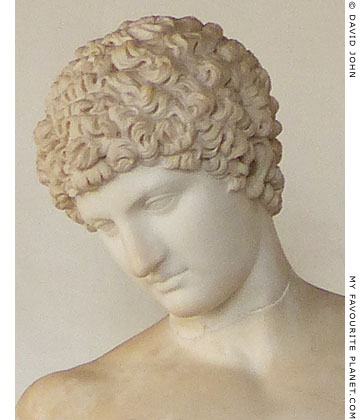

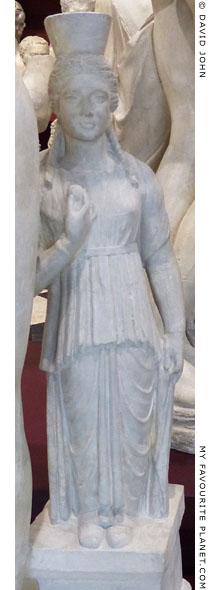

Classicistic Marble statue of Antinous as Apollo.

Parian Marble. Around 130-138 AD. Excavated 1st July 1894 [3]

behind the Temple of Apollo, Delphi. Height 184 cm.

Delphi Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1718. |

|

| |

This statue is considered important to the understanding of the iconography of portraits of Antinous since it is one of the few for which the archaeological context is known, and although the broken legs were repaired, unlike many other sculptures (particularly those from Rome) it has not been altered by modern restoration.

The findspot (see photo below) is one of the two rooms in the Roman period building west of the opisthodomos (rear porch) of the Temple of Apollo, close to the peribolos (περίβολος, perimeter wall). The function of the building is uncertain: it was dubbed "la Maison de l'Antinous" (the House of the Antinous) by the French archaeologists who discovered the statue, and is also referred to as the Propylaios and the House of the Pythia, due to inscriptions thought to refer to the building.

When it was unearthed the statue was still upright and described as shining, due to the special oil with which it had been polished. Holes drilled around the head were for attaching a laurel wreath, perhaps of gold or gilded bronze. The figure stands on its original black marble base. The lower arms and hands are missing, but it is thought that the figure may have held one of the attributes of Apollo, such as a lyre or a bow.

"It is one of the most stately statues of Hadrian's favourite in existence, and the surface has a brilliance like that of porcelain, produced by a polishing, which starts in Hadrian's time, and is produced by rubbing with wool dipped in oil and salve, the "Ganosis" often mentioned in literature.

The statue, in its blend of lost manhood and mawkish sweetness, is a typical specimen of the spirit of the Hadrianic age. The artist chose for his model a statue of Apollo from the school of Pheidias, known by two copies, one at Rome, found in the Tiber [see photo right], and one in Cherchel.

But while the powerful breast goes beyond the athletic model, the epigastrium is smooth and without muscles, and the oblique muscles of the abdomen and hip muscles are weak, while the long legs are almost feminine in their roundness and softness. In these details it was intended to do honour to the dainty youth, who is further characterised by lack of pubes, by elegant childish curls about his round cheeks, by the small dreamy eyes, the mystical sweetness of the lips and the delicate inclination of the head towards the left shoulder.

In the form of this late-antique god the Hadrianic sculptors sought to reconcile the irreconcilable; as pure classicists they brought to life again the male athlete's vigour of the fifth century, and at the same time they had to represent the prettiness of this Imperial favourite.

A Delphic inscription states that it was a priest of Apollo who proposed the introduction of the cult of Antinous at Delphi, and after his death Delphic coins were struck in his memory by order of the Amphictyonic Council. That Delphi, as little as Olympia, where was found a broken statue of Antinous, could resist the wish of the powerful Emperor, is easily intelligible but it is more wonderful that the cult of Antinous at Delphi, to judge by the circumstances of the find, lasted till the downfall of paganism.

Modern times find it hard to understand the readiness of ancient peoples to admit mortals among the gods, and in particular cannot believe in the sincerity of feelings towards this Imperial favourite. For it was not in this case a nation which had loved a fair man, as in his time Philip of Croton became a hero because of his beauty; but Antinous was raised from a low origin to the circle of the gods by the order of a ruler.

Hadrian based the apotheosis of his beloved on Egyptian religion. Herodotus in his time tells us that those who lost their lives by drowning in the Nile were honoured as sacred corpses where they came to shore [4], and thus the Emperor justified the admission of Antinous to Olympus after his mysterious disappearance.

On the Barberini Obelisk [see above], now standing on the Monte Pincio at Rome, the hieroglyphics relate how the Egyptian gods welcome Antinous into their circle, and how he prays to Harmachis for Hadrian, Sabina, and the whole empire, and begs the Father of the gods for fruitfulness of the Egyptian fields. In the dry Egyptian world of gods he was evidently a young and fresh figure, and at the same time drew closer the connexion between the old religion of the country and the cult of the Imperial house. In the whole heroizing of Antinous there is more expert policy and less love-rapture than one would a priori think.

That belief in Antinous really went down into the broad layers of the Egyptian people is shown by the numerous amulet coins with his image found in Egyptian graves, bored to wear round the neck with a ribbon, or to fasten on a mirror, often even imitated in cheaper lead. Terracotta slabs with his likeness were fastened on Egyptian sarcophagi as talismans for the dead. Even in the fourth century A.D. Antinous' name constantly appears in inscriptions on wooden mummy cases, and thus gives a sure proof of the strength and permanence of this belief.

To the expansion of the belief to the farthest parts of Greece and Asia Minor coins with his image bear witness, which are now known from more than fifty ancient cities. But that he was worshipped even in Hellas, centuries after his death, we learn for the first time from this find at Delphi.

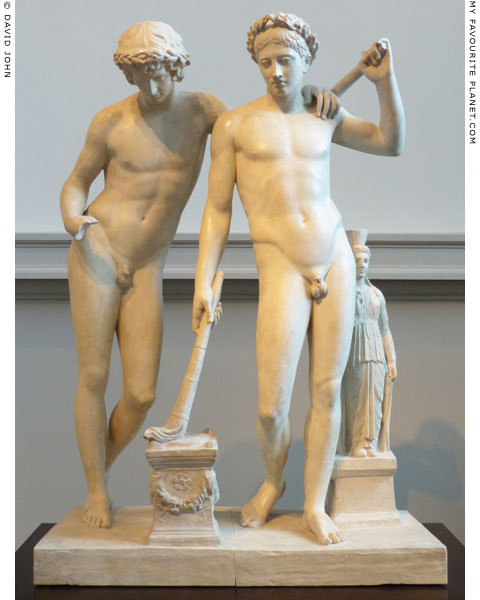

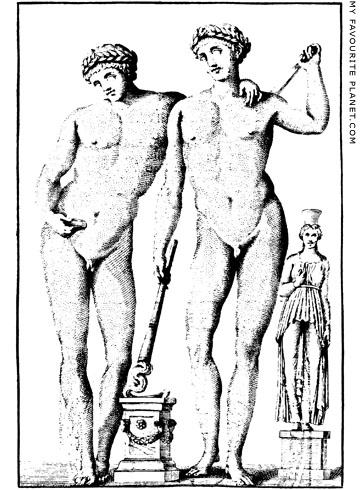

With the Antinous statue the cycle of Greek portraiture is complete; the development finishes, as it began, in abstract divinity. But what a difference between the two athlete types, one from the dawn, the other from the evening, of the development, the strong and pithy Delphic Twins [5], and the sweet and flaccid Antinous!"

Frederik Poulson, Delphi, pages 324-326. Translated by G. C. Richards. Gyldendal, London, 1920. At the Internet Archive.

The porcelain-like quality of the marble can still be admired, despite the marks and discolouring caused by centuries beneath the earth. However, the brilliance and sheen of the surface is more difficult to appreciate due to the flat museum lighting. |

|

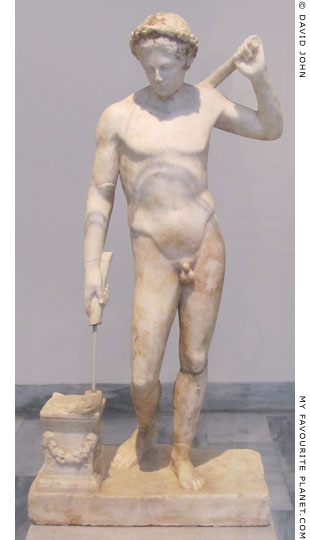

The "Tiber Apollo" statue with

which the Delphi Antinous

has been compared.

2nd century AD. The statue type

is thought to be a Roman imperial

period (early 1st century AD)

reworking of mid 5th century BC

Greek Classical models. Found in

fragments in 1891 in the River Tiber

near the Ponte Palatine, Rome.

The figure probably held a laurel

branch in the left hand and a bow in

the right. Pentelic or Parian marble.

Height 204 cm, with base 222 cm.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme.

National Museum of Rome.

Inv. No. 608. |

|

| |

The discovery of the Antinous statue in Delphi on 1st July 1894.

Source: M. F. Courby, Fouilles de Delphes, Tome II, Fig. 192, page 242.

École Française d'Athènes. E. de Boccard, Paris, 1927. |

| |

|

|

|

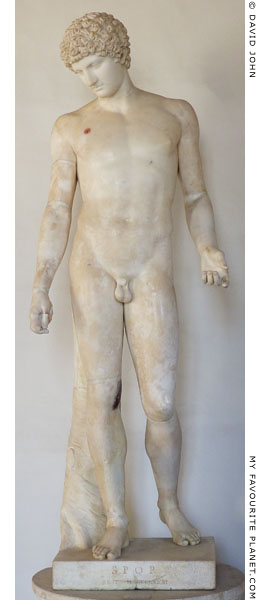

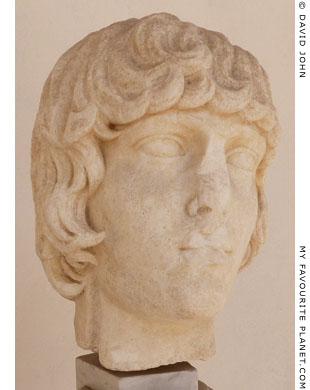

A fragmentary marble statue of Antinous from Olympia, Greece.

Around 130-138 AD. The fragments were found separately by archaeologists

between 1879 and 1939 in the Palaestra, at the sanctuary of Zeus, Olympia,

Peloponnese, Greece. Parts had been used to build a Late Roman wall at the

southwest of the Palaestra. Pentelic marble. Height 185 cm, height of head

42 cm, height crown to chin 25.5 cm.

Although the museum's labelling and literature now confidently claim the

statue to be a portrait of Antinous, perhaps as an athlete, some historians

have expressed doubts. It has been described as depicting a youth with

features similar to Antinous, and other identifications have been suggested.

Olympia Archaeological Museum. Inv. Nos. Λ 104 and Λ 208.

Currently exhibited in the Museum of the History

of the Olympic Games of Antiquity, Olympia. No. 403. |

|

| |

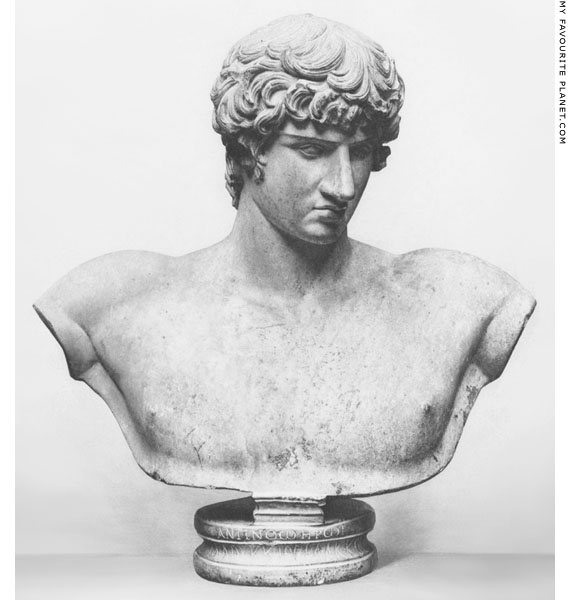

A restored, larger than lifesize marble bust of Antinous, sometimes referred to

as the "de Clercq bust", said to have been found in the mid 19th century in Syria.

It is the only known ancient portrait of Antinous, apart from coins, identifiable by

an inscription. For scholars it provided further confirmation of the theory that the

many similar sculptures discovered since the early 17th century are depictions

of Emperor Hadrian's deified young favourite.

130-138 BC. Thasian marble. 130-138 AD.

Height 83.7 cm, width 78 cm, diameter of round base 27.5 cm.

Private collection.

Image source: André de Ridder, Collection de Clercq, Catalogue, Tome IV:

Les marbres, les vases peints et les ivoires, planche XV. Ernest Leroux,

Paris, 1906. At Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

|

The nose, upper lip and right shoulder of the bust are damaged, and have been restored, but otherwise it is in fine condition. The round moulded base is inscribed in Greek with a dedication to Antinous as hero by an unknown Roman citizen named M. Lucius Flaccus (the M. probably standing for Marcus):

ΑΝΤΙΝΟW ΗΡWΙ

Μ ΛΟΥΚΚΙΟC ΦΛΑΚΚΟC

Antinoo heroi

M. Loykkios Flakkos

To the hero Antinous

(dedicated by) M. Lucius Flaccus

Inscription IGLSyr 4 1300. [6]

The identity of Marcus Lucius Flaccus is not known, although there have been a number of suggestions, including that he may have been a senior member of the gens Valeria, a prominent Roman clan, could have been a military or civil official, and was perhaps even involved in the suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt in Judaea in 132 AD, two years after the death of Antinous. [7]

There appears to be no exact information about when, where or how the bust was found or acquired by Antoine Napoléon Aimé Péretié (1808-1882), chancellor of the French Consulate in Beirut 1844-1882, its first known modern owner. Described as a passionate amateur connoisseur of antiquities, he engaged in and commissioned private archaeological excavations, amassing a large, varied collection of ancient artefacts from the Levant and Cyprus. He also obtained antiquities for wealthy clients, meaning that he was active on the so-called "art market" of the time, often a euphemism for the legal or illegal trade and transport of objects dug up by treasure hunters, grave robbers and amateur archaeologists.

In 1859 he met and befriended the French photographer (later industrialist and politician) Louis de Clercq (1836-1901), who was making his visit to Beirut as part of a French archaeological mission to Syria. The relationship proved advantageous to both men, and Péretié acquired antiquities for de Clerq, who started his own collection. Later de Clerq purchased the bust and several other objects from Péretié's collection. [8]

Following de Clercq's death in 1901 much of his collection was owned until 1967 by his nephew and heir Comte Henri Louis Marie Martin de Boisgelin (1897-1985). While most of the objects were donated to Louvre and the

Cabinet des Médailles, Paris, others, including the Antinous bust, were put on sale. At some time after, the modern parts of the bust added during a restoration (commissioned by de Clercq?) were removed. The latest of several owners was the late businessman and philanthropist Clarence Day (1927-2009), who had one of the finest private antiquities collections in the United States. On 7th December 2010 the bust was sold to a private collector in an auction at Sotheby's, New York, for $23,826,500. [9]

In 2018 the bust made a rare public appearance when it was made the centrepiece of the exhibition Antinous: Boy made God at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 25 September 2018 - 24 February 2019. Exhibition publicity referred to it as "one of the most important surviving portraits of Antinous". Prior to the exhibition, in 2011 the Ashmolean undertook new conservation restoration work on the bust and created a new cast copy to be displayed in the museum. [10] |

|

|

| Antinous |

The findspot of the "de Clercq bust",

Banias or Baniyas? |

|

|

|

There has long been confusion about where this bust of Antinous was discovered, as some publications state Banias and others the similarly-named Baniyas. Both places where once in the Roman province of Syria and were part of Ottoman Syria in the 19th century when the bust was found and first discussed by scholars. Although these two modern names appear - or, rather, sound - similar, they are both corruptions of quite different, unrelated ancient names.

Banias is an important archaeological site, inland, on the Golan Heights, today in northern Israel. Formerly part of Syria, it was occupied by Israel during the Six Day War in 1967. The ancient town, by the 20th century merely a village, was abandoned and the houses were demolished. It was known from the Hellenistic period as Paneas (Greek, Πανιάς, Πανεάς or Πανειάς; Latin, Paneas) or Paneion (Πάνειον), named after a large sanctuary of the Greek god Pan. During the Roman period it was also known as Caesarea Philippi (Καισαρεία Φιλίππεια). [11] Both names were mentioned by ancient authors, including Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 5, chapters 15 and 16).

Baniyas, on the other hand, is around 217 kilometres to the northeast, a Mediterranean seaport in the modern state of Syria, 55 km south of Latakia. The town has been identified as ancient Balanea, originally a Phoenician settlement, later mentioned by a number of ancient authors, including Pliny the Elder (Latin, Balanea, Natural History, Book 5, chapter 18) as well as the Greek geographers Claudius Ptolemy ("Βαλανέαι", Geography, Book 5, chapter 15, section 3) and Strabo ("Βαλαναία", Geography, Book 16, chapter 2, section 12).

Much of the confusion concerning their names is due to the historical lack of standardization in spellings of placenames in original languages and scripts (in this case Arabic) and transcriptions into the Latin alphabet by scholars writing in various European languages (mainly French, German and English).

There have been inconsistencies in spellings of names from antiquity upto the present day, even on official documents and signs, so such uncertainties and errors continue to seem inevitable. It appears that the modern Arabic names for both places are written in the same way (according to Wikipedia, بانياس,). Paneas is said to have become Banias due to the lack of the letter P in Arabic. Some maps of the area mark either place as "Banias" or "Baneas", while others show both places as "Banias". Perhaps more surprisingly, recent Israeli archaeological reports refer to Banias/Paneas/Caesarea Philippi as "Baniyas". [12] |

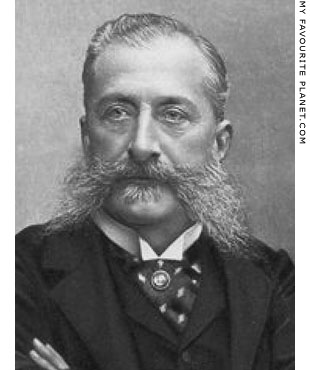

Photo of Louis de Clercq (1836-1901),

French industrialist, photographer,

explorer and collector of antiquities.

Rotogravure by Paul Dujardin, from

a photo by Charles Pierre Ogerau.

In: Anton de Ridder, Collections de

Clercq, Tome III: Les bronzes,

frontispiece. Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1905. At

Gallica, Bibliothèque Nationale de France. |

|

|

So how, when and where was this bust found? Unfortunately, we have no published testimony directly from Aimé Péretié or his associates, and neither he nor anyone since has published a detailed account of his amateur archaeological exploits or collecting and dealing activities, which he (or his successors) may have preferred to surround with a veil of discretion.

The first publication dealing with the bust was the relatively short 1879 article (fourteen and a half pages with no illustrations) on Greek and Latin inscriptions in his collection in Beirut by the Frenchmen Pierre Marie Mondry Beaudouin (1852-1928), Greek scholar, and Edmond François Paul Pottier (1855-1934), art historian and archaeologist (he also later worked on the catalogue of the Louis de Clercq Collection, see below). They pointed out that details of the greater part of Péretié's "remarkable collection of antiquities, bronzes, terracottas, jewellery, precious stones, medals, originating from every part of Syria" had not yet been published (page 257). A comprehensive catalogue of the collection was never to appear.

In their terse description of the bust, Beaudouin and Pottier wrote that it was found at "Panias", without further explanation. This is their only mention of this placename, by which we may assume they meant Banias/Paneas/Caesarea Philippi. But can we be sure?

"Piédestal supportant un buste d'Antinoüs; trouvé à Panias. Marbre blanc."

ΑΝΤΙΝΟW ΗΡWΙ

Μ ΛΟΥΚΚΙΟΣ ΦΛΑΚΚΟC

Ἀντινόῳ ἥρωϊ

Μ. Λούκκιος Φλάκκος.

("Pedestal supporting a bust of Antinous; found at Panias. White marble.")

M. Beaudouin, E. Pottier, Collection de M. Péretié: Inscriptions, Number 2, page 259. In: Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique (BCH) Volume 3, 1879, pages 257-274. At persee.

From the article it is not clear what access the authors had to items in the collection or any documents associated with it, or what information they were given by Péretié. [13]

Considering the size, scope, historical and art-historical importance of the Péretié Collection, not to mention the consequent high values achieved by some of its artefacts on the art market, it seems surprising that deeper, more comprehensive accounts have not been published. So far I have not discovered what original documents (reports, notes, diaries, financial accounts, inventories, etc) concerning Péretié's activities are known or still exist, or what research has been made into the subject. One may also expect that Beaudouin, Pottier or other contemporary scholars may have left notes and documents accumulated during their research.

Nearly three decades later the French Classical archaeologist André de Ridder (1868-1921) featured the Antinous bust in the third volume of a catalogue of the Collection de Clercq in Paris, of which many objects from the Péretié Collection had meanwhile become part. The catalogue grew to eight volumes, gradually published between 1888 and 1912, work continuing for some years after Louis de Clercq's death. Volume 3 also contained what were for the time excellent photographic plates of many of de Clerq's marbles, including three of the bust. In his description of the bust's provenance, even more sparely written than that of Beaudouin and Pottier, de Ridder called the place of origin "Banias":

"Buste d’Antinoüs. - Anc. collection Péretié. Banias."

("Bust of Antinous. Formerly in the Péretié Collection. Banias.")

André de Ridder, Collection de Clercq, Catalogue Tome IV: Les marbres, les vases peints et les ivoires, Number 35, pages 39-40 and plates 15-17. "Publié par les soins de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, et sous la direction de MM. de Vogüé, E. Babelon, E. Pottier." Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1906. At Gallica, Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Once again, with no other apparent indication, it could be assumed that the reference is to Banias, i.e. Paneas/Caesarea Philippi. However, in an appendix at the back of the volume, Table IV, Table des provenances (page 213), the provenance of the bust (No. 35) and one other artefact (No. 116, not noted as being from Péretié's collection [see note 13]) are given as "Banias (Balanée)", i.e. Baniyas (Balanea). [14] de Ridder did not provide the source of this claim, and we do not know if he was aware of the distinction between Baniyas (Balanea) and Banias (Paneas), which he referred to as "Caesarea Paneias" and "Paneion" (page 35). He does cite the Beaudouin and Pottier article, and we might deduce that he considered their "Panias" to be an error. But Edmond Pottier is credited as one of the catalogue's directors (see citation above), even though we do not know to what extent he and de Ridder collaborated on this volume or particular entries.

A number of sources often cited in connection with the bust and its provenance, mostly brief mentions in academic articles, also prove to be dead ends in terms of answering the Banias/Baniyas question. [15] Pirro Marconi's substantial and often-cited 1923 survey of Antinous portraits, Antinoo, saggio sull'arte dell'età adrianea , long-considered a standard work on the subject, had nothing to add to the sum of knowledge concerning the bust. The shortest of entries appears at the very end of his Catalogue of works (Parte Prima - Catalogo delle opere). Apart from incorrectly referring to its owner as "Samuel Pérétié", he cites only the Beaudouin and Pottier article, and appears unaware that the bust had long-since passed into the de Clercq Collection, or of de Ridder's catalogue. [16]

In 1955, half a century after de Ridder's catalogue, Louis Jalabert and René Mouterde, French Jesuit priests and archaeologists who had both worked in Lebanon, included de Clercq's Antinous bust in their four-volume work on Greek and Latin inscriptions from Syria [see note 6], writing that it was from "Bânyâs-Balanée" along with a number of other items in their catalogue.

"Bânyâs-Balanée a fourni à Péretié un grand nombre d’antiquités." (page 51)

("Baniyas-Balanea provided Péretié with a large number of antiquities.")

They were careful to distinguish the place from the more southerly Banias (Paneas), referring to it as "Bânyâs du Sud" ("Banyas of the south") as if it were another place of the same name:

"La petite ville de Balanée ... est aujourd'hui Bânyâs, en pays alaouite (à distinguer de Bânyâs du Sud, en territoire syrien = Πανείον - Caesarea Philippi, Paneas)." (page 49)

("The small town of Balanea ... is today Banyas, in Alawite territory (as distinct from Banyas of the south, in Syrian territory = Πανείον - Caesarea Philippi, Paneas).")

Their assertion that the bust was from Baniyas/Balanea has been taken as proof by some scholars. However, they provided no evidence, merely citing the article by Beaudouin and Pottier and the de Ridder catalogue.

Among the more recent publications which state that the bust was found in Banias/Paneas/Caesarea Philippi, is a 1999 article by Elise A. Friedland on sculptures discovered there at the sanctuary of Pan. [17] She cited Hugo Meyer's 1991 book Antinoos, another standard work on archaeological objects associated with Antinous. However, Meyer wrote not only that the bust was found in "Baniyas in Syria" but that Péretié's collection was also there, rather than in Beirut. He, in turn, cited Beaudouin and Pottier, who had claimed the bust was from "Panias". It seems as if he, like a number of other scholars who have written about the bust, was not particularly interested in its provenance or the distinctions of Syrian geography.

"Kat. I 77. Kunsthandel Würzburg, 1983 (A. Neuhaus): Büste ehem. in der Sammlung de Clercq, Paris; davor in der Sammlung Péretié in Baniyas in Syrien; gefunden in Baniyas [s. die Bibliographie (Beaudouin und Pottier)]." [18]

("Catalogue No. I 77. Art market Würzburg, 1983 (A. Neuhaus): bust formerly in the de Clercq Collection, Paris; previously in the Péretié Collection in Baniyas in Syria; found in Baniyas [see the Bibliography (Beaudouin and Pottier)].")

Freidland's article dealt with the sculptures found at Banias/Paneas/Caesarea Philippi during excavations there 1988-1994, the subject of her 1997 dissertation, which she later revised as a book, published in 2012. Doubt concerning the provenance of the Antinous bust may have been one of the reasons she consigned discussion of it to an appendix, the main reason presumably being the fact that it definitely was not found during the relevant exavations. [19]

In her review of Friedland's book, Irene Bald Romano wrote of the bust's alleged findspot of "Caesarea Philippi/Panias":

"If the provenience from the Paneion is correct, it suggests a sanctuary with imperial significance in the Hadrianic period. If it is from the city site of Caesarea Philippi, it is noteworthy that only one, as yet unpublished, sculpture [i.e. the Antinous bust] has been found in extensive excavations at the city site (23, n. 7), founded in 2 BC by Herod’s son Philip just to the south of the Sanctuary of Pan." [see note 19]

John Francis Wilson, former Administrative Director of the excavations at Banias/Paneas/Caesarea Philippi, had earlier expressed his belief that the bust was discovered there in his 2004 book Caesarea Philippi: Banias, the lost city of Pan, and had also suggested some speculative consequences concerning the "imperial significance" of the site, particularly of connections with Hadrian:

"Into this general historical context we may insert a number of intriguing clues as to what was happening in Banias. First, there is the beautiful and well-preserved bust of Antinous that was discovered in the mid-1800s in Banias by M. Pétretié, Chancellor of the French Consulate in Beirut. It should be dated somewhere between 130 and 138 AD. Inscribed 'To the hero Antinous', this sculpture suggests strong Hadrianic connections in Banias. The dedicant, one 'M[arcus] Lucius Flaccus', is otherwise unknown. If the imperial cult was still centred in Herod's Augusteum, the bust may have stood in some place of honour in that temple. If not, it must have been located at some place within the growing cult complex near the cave and springs or among the monuments of the city centre." [20]

In his footnotes Wilson cited André de Ridder and Hugo Meyer, neither of whom expressed such a belief, and even speculated that the bust "may have been carved in Antioch" (here he cited Friedland's 1997 dissertation, pages 243-244).

Although Sotheby's 2010 description of the bust - Lot 9 in the auction - states it was found at Banias/Paneas/Caesarea Philippi in the Golan Heights, for some reason the name "Baniyas" was added for the location. It is as if they were hedging their bets on the issue:

"Found at ancient Banias (or Paneas), later Caesarea Philippi (modern-day Baniyas in the Golan Heights)" [see note 9]

A short article to accompany details of the Sotheby's lot generally followed the arguments used by Wilson, suggesting that the bust may have been set up in a place of honour at Paneas/Caesarea Philippi, such as the Augusteum. It even called Flaccus "a local military figure or magistrate of Syria", although there is no evidence for this, "a descendant of one of the most prominent patrician families of Rome, the Gens Valeria", who "acted as a public benefactor of the city of Banias by acquiring for her a finely carved and polished portrait bust of Antinous". It also attempted to explain why Flaccus chose to have the dedicatory inscription carved in Greek rather than Latin [21].

The publicity for the 2018 Ashmolean Museum exhibition stated:

"Bust of Antinous with Greek inscription. Discovered in Balanea, Syria in 1879." [see note 10]

As we have seen above, 1879 was the date of the first publication of the bust by Beaudouin and Pottier, but I have found no previous source that states it was found or even entered Péretié's collection in that year. Other publications have carefully avoided giving a date for the sculpture's discovery.

At least those scholars who support the idea that the bust is from Paneas/Caesarea Philippi can imagine possible spacial and cultural contexts for the sculpture. The popularity of this kind of speculation may partly be due to the increased interest in the place since the recent archaeological discoveries made there, as well as the attractiveness of the site and its surrounding natural environment. On the other hand, members of the Baniyas/Balanea camp are denied this luxury as long as the archaeological and topographical knowledge of the ancient port remain insufficient to fuel such conjecture. Given the present terrible political situation in Syria, this situation is unlikely to change in the near future.

This may all sound more than a little academic or trivial, but it typifies the kind of muddle in which historical facts can get tangled and lost, and the problems faced by modern researchers and writers. From at least the time of the pioneering German archaeologist Konrad Levezow (1770-1835), there has been an awareness that precise information about the location and circumstances of archaeological finds can be crucial to gaining understanding of not only the objects themselves but also the nature of the sites as well the people who used the spaces (houses, marketplaces, sanctuaries, cemeteries, etc). Such data also adds to the quality as well as the quantity of the information gleaned from finds.

Since the first mention of the bust's provenance in print, generations of scholars have written that it was found at one place or the other, as if it was fact rather than opinion, without qualifying their preference or providing any evidence. Thereafter much speculation and conjecture has been based upon these opinions. But it appears that nobody has made an attempt to discover the truth, perhaps by trying to find whether the trail back to the sculpture's discovery can still be traced. Such research may seem like drudgery to some and a rewarding adventure to others, but perhaps some enterprising researcher will some day take on the challenge. |

|

|

| |

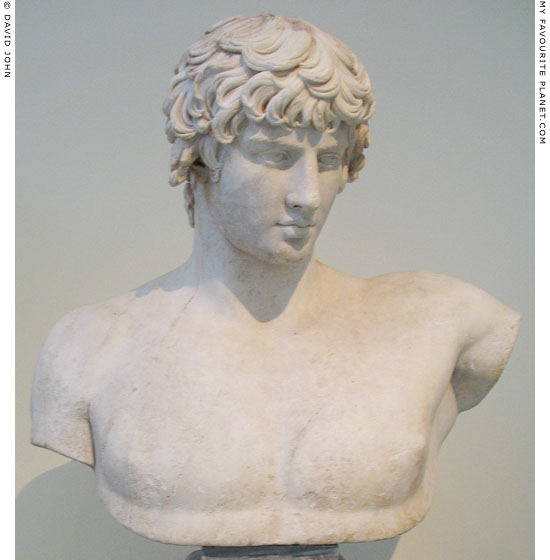

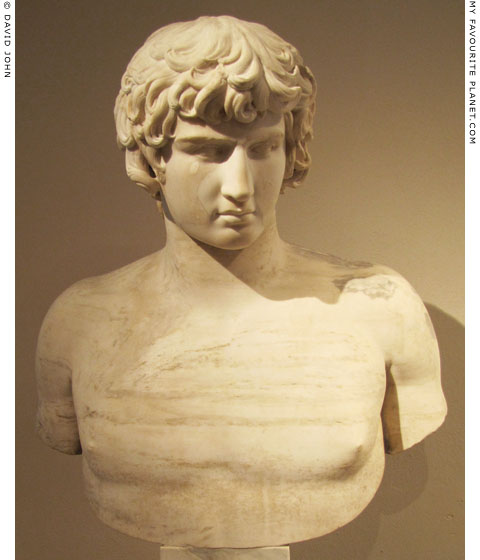

Marble bust of Antinous, found in 1856 in Patras, Peloponnese.

Thasian marble. 130-138 AD. Height 67 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 417.

One of two busts of Antinous found in Patras and now in the Athens museum.

The other, Inv. No. 418, is not in such a good condition, and is not on display.

This bust is an example of Antinous portrait sculptures designated "Haupttypus,

Variante A" (Main Type, Variant A), and is considered very closely related to

other marble busts of the type, including the bust from Syria (see above)

as well as those in the Louvre (Inv. No. Ma 1082, the "Antinoüs d’Écouen"),

the Prado, Madrid (Inv. No. 60-E) and the Uffizi Gallery, Florence (Inv. No. 327). |

| |

Restored portrait head of Antinous on a modern bust.

130-134 AD. From Rome. Probably from the Polignac Collection.

Height of bust with head 98 cm; height of head 27 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 364.

|

Purchased in Rome around 1770 by the art dealer Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi, acting as an agent for King Friedrich II of Prussia (Frederick the Great, 1712-1786). It was then restored in the workshop of the sculptor and restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi in Rome. On its arrival in Berlin the restored bust was considered by Matthias Oesterreich to be a modern replica, and at first (before 1772) it was set up in the gardens of the Neues Palais, Sanssouci, Potsdam. The work was reevaluated in 1830, after which it was moved to the Königliche Museum in Berlin.

See two Antinous statues purchased for Frederick the Great below, here and here. |

|

|

| |

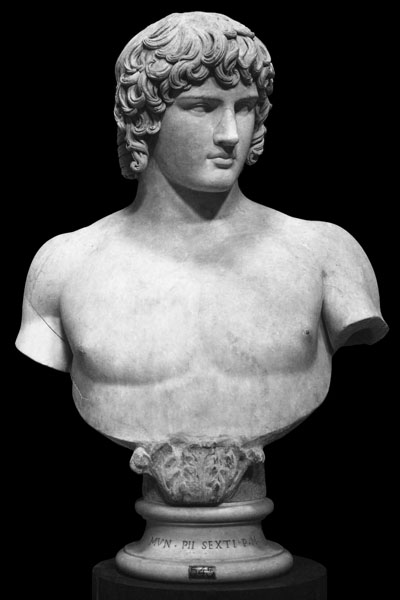

Colossal marble bust of Antinous.

Found in 1790 at Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli, near Rome.

The hairline marking the beautifully restored nose

is evident. Height 100 cm (without modern socle).

Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums, Rome. Inv. No. 251.

Photo by James Anderson (1813-1877), taken around 1860. |

| |

The "Ludovisi Antinous", an ancient marble portrait bust

of Antinous with a modern face added by restorers.

Luni (Carrara) marble. Height 68 cm, including the modern socle.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome.

Inv. No. 8620. From the Ludovisi Collection.

|

This photo of the "Ludovisi Antinous" (taken in April 2015) originally appeared further down this page, among copies and doubtful artworks associated with Antinous. But it has recently been redeemed and shown to have originally been a genuine ancient portrait bust of Hadrian's favourite.

As with other busts of Antinous, he is shown with typically wavy hair, and a broad chest with smooth muscles. His head is turned slightly to the left and downwards, as in statues of deities and emperors, looking down from their high pedestals at the viewers or worshippers below.

But anyone who has seen this bust or even photos of it, will have noticed that the face does not quite fit the head. Viewed from the left it does not look too bad. The face has been carved competently but it seems somewhat bland and a little too small. From the right, however, the face has obviously been badly stuck on to the front of the head and does appear to belong there at all.

It has long been thought that the ancient bust, perhaps portraying someone else, was given a modern face of Antinous by a restorer for a client, or so that it could be more easily be sold in Rome where there was a good market for portraits of the young man. This kind of creative restoration was common practice in Italy after the Renaissance, and particularly in the 18th century, as the demand for ancient sculptures increased among wealthy tourists and private collectors. A number of famous "ancient" statues have since turned out to be confections created in the workshops of modern sculptors.

The date and place of the bust's discovery are unknown, but it may have been found or acquired in the early 17th century by Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi for his collection in the Villa Ludovisi, Rome (see also the "San Ildefonso Group" below). A larger-than-life-size head and chest of "Antonio" is recorded in a 1641 inventory of the Palazzo Grande on the Ludovisi estate. The German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann noted the odd composition of the bust, seen during his visit to the villa in 1756: "The head is noticably new. The back of the head and chest are old." ("Der Kopf ist wahrhaftig neu. Der Hinter Kopf u. die Brust sind alt." Ville e palazzo, page 250)

The bust was mentioned a number of times during the ensuing centuries. In 1901 it was among the 104 ancient sculptures from the Ludovisi Collection sold by the Boncompagni Ludovisi family to the Italian state. The artworks were moved to the National Museum of Rome at the Baths of Diocletian, then transferred to the Palazzo Altemps in 1997.

In 1898 Charles Lawrence Hutchinson (1854-1924), the first president of the Art Institute of Chicago, purchased a marble relief head of Antinous (see photos, right) for his private collection from the artist and antiquarian Attilio Simonetti (1843-1925) at the Palazzo Odescalchi, Rome. Following Hutchinson's death in 1924 the relief was given to the Art Institute.

In an article about the relief published in Art in America in December 1913, Frank B. Tarbell, Art Institute curator, asserted that it was a fragment from a statue or bust carved in the round, and that it belonged typologically to a group of portraits distinguished by a common hairstyle. [22] Both his claims were eventually proved to be correct, and by the early 1960s the head fragment had been freed from the marble plaque and plaster restorations. |

The fragment of a marble portrait

head of Antinous in Chicago.

130-138 AD. Luni (Carrara) marble.

Height 31.7 cm, width 31 cm, depth 17 cm.

Art Institute of Chicago. Inv. No. 1924.979.

Purchased in Rome in 1898 from Attilio

Simonetti by Charles Lawrence Hutchinson

for his private collection. Bequeathed to

the institute in 1924.

CC0 Public Domain photo, courtesy

of the Art Institute of Chicago. |

| |

The head of Antinous in Chicago as

a relief, before it was freed from the

marble plaque and plaster restorations.

Image source: see note 22. |

| |

After examining the "Ludovisi Antinous" bust in the Palazzo Altemps, in 2005 W. Raymond Johnson, an Egyptologist at the University of Chicago, suggested to the Art Institute that the museum’s fragment may have been originally part of the bust. Over the following decade Karen Manchester, Chair and Curator of Ancient and Byzantine Art at the Art Institute led an international research project aimed at testing Johnson's hypothesis, entailing cooperation between scholars, technicians and other specialists and close collaboration with the University of Chicago, the Palazzo Altemps and other institutions. A number of techniques were used, including laser scanning, 3D computer modelling and 3D printing, as well as isotopic and petrographic analysis of the marble samples from both the Ludovisi bust and the Chicago fragment. These latter tests showed such a close match that it seems very likely that both pieces are from the same block of stone.

In a moment of truth in 2013, a copy of the fragment was found to fit exactly to a copy of the Ludovisi bust with the modern face "removed". From this fit a plaster cast has been made to demonstrate the bust's original appearance.

Naturally the matching of the Chicago fragment to the Ludovisi bust has been hailed as a spectacular discovery, a triumph of scholarly research and international collaboration, as well as the use of the latest technology. The exhibition A portrait of Antinous, in two parts in 2016 in the Art Institute of Chicago (2 April – 5 September), also shown in the Palazzo Altemps as Antinoo, un ritratto in due parti (14 September 2016 - 15 January 2017), celebrated the discovery and the collaboration between the two institutions. [23] |

|

|

| |

The "Townley Antinous", a marble head

of Antinous as Dionysus, wearing an ivy

wreath, on a modern bust.

130-138 AD. Excavated in 1770 near

the Villa Pamphili, on the Janiculum Hill,

Trastevere, Rome. Found with parts of the

statue to which it belonged built into a wall.

The head had been used as a foundation

stone. Parian marble. Height 60 cm.

British Museum.

Inv. No. 1805,7-3.97 (Sculpture 1899).

From the Townley Collection. |

|

Marble head of Antinous as Dionysus,

wearing a laurel wreath with berries,

on a modern bust.

"Haupttypus", variant B. Pentelic marble.

Nose and piece on top of head with

attachment restored. Height 72 cm;

antique part 38.5 cm.

Galleria, Palazzo Nuovo, Capitoline

Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 294.

From the Albani Collection (Inv. No. B 179). |

|

| |

Marble busts of Hadrian and Antinous exhibited together in the British Museum.

For some reason, the bust of Hadrian, also from the Townley Collection, has

been placed further forward than the "Townley Antinous" (see above).

The only known instance in ancient art in which the pair are thought to appear

together is on the tondi of the Arch of Constantine in Rome (see below).

Hadrian bust, Roman 117-138 AD. Probably from Rome.

Inv. No. 1805.7-3.94 (Sculpture 1897). |

| |

Pausanias on Antinous worshipped as Dionysus in Mantineia, Arkadia, Peloponnese:

"Antinous too was deified by them; his temple is the newest in Mantineia. He was a great favourite of the Emperor Hadrian. I never saw him in the flesh, but I have seen images and pictures of him. He has honours in other places also, and on the Nile is an Egyptian city named after Antinous. He has won worship in Mantineia for the following reason. Antinous was by birth from Bithynium beyond the river Sangarius, and the Bithynians are by descent Arcadians of Mantineia.

For this reason the Emperor established his worship in Mantineia also; mystic rites are celebrated in his honour each year, and games every four years. There is a building in the gymnasium of Mantineia containing statues of Antinous, and remarkable for the stones with which it is adorned, and especially so for its pictures. Most of them are portraits of Antinous, who is made to look just like Dionysus. There is also a copy here of the painting in the Cerameicus which represented the engagement of the Athenians at Mantineia. [24]

. . .

There are roads leading from Mantineia into the rest of Arcadia, and I will go on to describe the most noteworthy objects on each of them. On the left of the highway leading to Tegea there is, beside the walls of Mantineia, a place where horses race, and not far from it is a race-course, where they celebrate the games in honor of Antinous. Above the race-course is Mount Alesium, so called from the wandering [ale] of Rhea, on which is a grove of Demeter."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 9, sections 7-8, and chapter 10, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

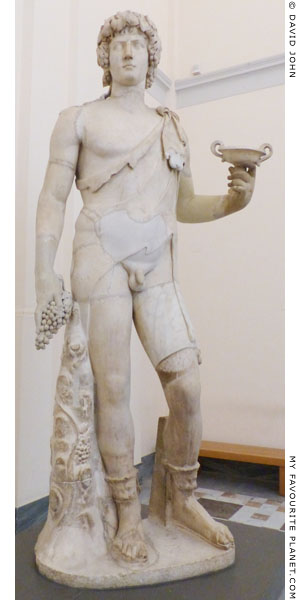

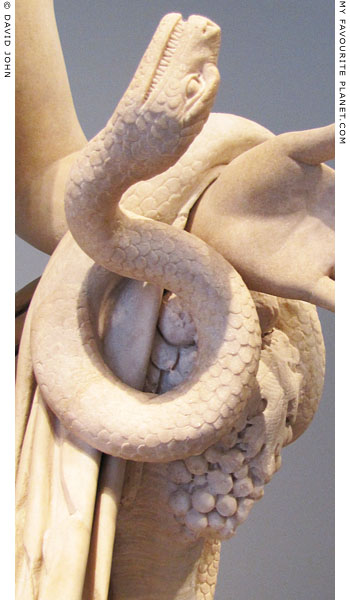

Colossal marble statue of Antinous as Bacchus/

Dionysus, wearing an ivy wreath and panther

skin, and holding a cup in this left and and a

bunch of grapes in the right.

Roman creation, 2nd century AD. Provenance

unknown. Recorded as being in the Farnese

Collection in Rome from 1644. Height 297 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Inv. No. 6314.

The other marble statue of Antinous in the Naples

museum, also from the Farnese Collection, is known as

the "Antinous Farnese". Height 200 cm. Inv. No. 6030. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

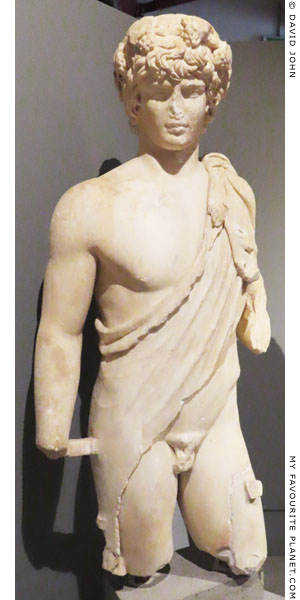

Marble statue of Antinous as Dionysus wearing a crown of ivy leaves and bunches of grapes,

and a panther skin, knotted at his left shoulder and wrapped around the otherwise naked torso.

Found in the early 20th century during archaeological excavations of the public baths at the thermal

springs in ancient Aidepsos (Αιδηψός), northwestern Euboea. Height 136 cm, height of head 29 cm.

New Archaeological Museum "Arethousa", Chalkis, Evia. Inv. No. MX 32.

Formerly in the (Old) Archaeological Museum of Chalkis.

See also statues of Dionysus wearing an ivy wreath and panther skin.

|

|

Aidepsos was said to be a haunt of the mythical hero Herakles, who, weary from his labours, enjoyed the healing and recuperative powers of its sulphurous springs. It became a renowned spa town, frequented by many well-to-do Greeks and Romans, including the Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (138-78 BC), who went there in 86 BC to have his gout treated. It has even been dubbed "Sulla's baths". There is no evidence that either Hadrian or Antinous ever visited the place, although apart from this statue, a marble base for a bronze statue has beeen found with an inscribed dedication (IG XII 9, 1234) to the emperor as "Olympios", a title he took in 128 AD.

This statue was among several finds, most from the Roman period, discovered in 1905 during excavations by the Greek archaeologist Georgios A. Papavasileiou (1846-1915), the results of which were published in 1907. [25] |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Black marble statuette of Antinous as Dionysus.

130-134 AD. Provenance unknown. From the collection of Giovanni Grimani (1506-1593),

bishop and patriarch of Aquileia, in Venice. Nero antico marble from Göktepe, near

Aphrodisias (Turkey). Restored height 86.5 cm; height of surviving ancient work 57 cm.

Although the figure has been compared to statues of Apollo, it was identified

as Antinous-Dionysus, and the staff he holds in his left hand is thought to be

part of the wine god's thyrsos (see Dionysus).

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 362.

Donated in 1854 by Anton Steinbüchel von Rheinwall. |

|

| |

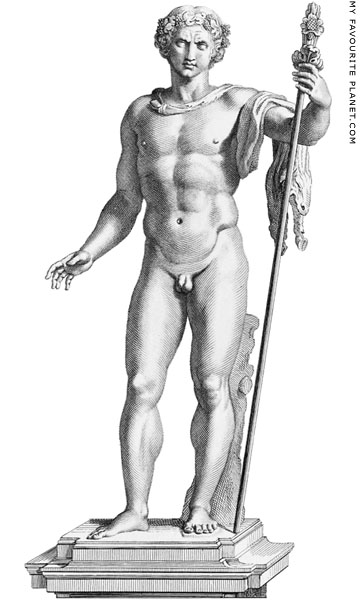

Early 18th century engraving of the "Antinous Casali",

a marble statue of Antinous as Dionysos. Height 235 cm.

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Inv. No. 1960.

|

Found around 1698-1704 in the garden of the Villa Casali, on the Caelian Hill, Rome, thought to be the location of the house of the Roman senator and governor Gaudentius (late 4th century AD). It was exhibited at the Villa Casali and admired by many visitors, including Johann Joachim Winckelmann.

When the villa was demolished in 1884, the Casali family sold the statue, and in 1888 it was in the possession of the art collector G. Scalambrini. He sold it to the Belgian art collector Léon Somzée, who took it to Brussels. In 1903 Carl Jacobsen purchased it for the newly built Glyptothek in Copenhagen, which opened 1906. The left arm and thyrsos, restorer's additions, were replaced by new parts during the latest restoration in 2001.

Image source: engraving by Domenico de Rossi (1659-1730), in: Paolo Alessandro Maffei (1653-1716), Domenico de Rossi, Raccolta Di Statue Antiche e Moderne Data In Luce Sotto I Gloriosi Auspici Della ... Papa Clemente XI, CXXXVIII, Bacco, pages 128-129 and Plate 138. Stamperia alla Pace, Rome, 1704. At the Internet Archive.

Also at: digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/maffei1704, Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Marble statue of Antinous, of the type

Dionysus or Asklepios, standing next

to the Delphic omphalos.

Found in 1860 in Eleusis. 2nd century AD.

Height 167 cm.

The statue may have stood in the outer

courtyard of the Sanctuary of Demeter.

Antinous was with Hadrian and the

imperial entourage at the celebration

of the Eleusinian Mysteries in 128/9 AD,

and may have been initiated into the cult

at Eleusis (see Demeter). An ephebic

festival known as the Antinoeia was

established there in his honour.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 5092. |

|

|

|

| |

Egyptianizing head of Antinous as the Egyptian god Osiris.

Circa 130-138 AD. Red sandstone. Perhaps from the Serapeum of

Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli (see below). Height 34 cm, width 40 cm, depth 37 cm.

Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum, Dresden. Inv. No. Hm 023.

|

Purchased in 1728 in Rome for August the Strong (August II. der Starke, 1670-1733), elector of Saxony and king of Poland, from Prince Augusto Chigi (1662-1744), among 160 sculptures acquired from the collection of his father Prince Agostino Chigi (1634-1705). August's agents also purchased 34 works from the collection of Cardinal Alessandro Albani.

Previously thought to represent Isis or a sphinx, the head was only identified as a portrait of Antinous at the beginning of the 19th century. The stone certainly looks like deep red sandstone, as stated by the museum labelling and literature and a number of other sources. A few sources state quartzite, and at least one author has suggested it may be Egyptian granite.

Exhibited in the Albertinum, Dresden since 1730, it is currently (2017) in a makeshift (and dismally lit) temporary exhibition of ancient sculptures in crowded display cases, following the removal of the antiquities collection from the museum's basement due the flooding of the River Elbe in 2002.

See: Bildnis des Antinoos-Osiris, at the Dresden State Museums website. |

|

| |

Rosso antico marble (ancient red; Latin, marmor taenarium) statue

of Antinous as Osiris, found in the 16th century at Hadrian's Villa,

Tivoli, near Rome. Restored height 226 cm (with plinth 243 cm).

State Museum of Egyptian Art, Munich. Inv. No. GL WAF 24.

Purchased from the Albani Collection.

The photo shows the statue with the plinth, arms, legs and

other parts added by restorers in the 19th century. These

additions have since been removed. Present height 135 cm.

A very similar statue of Antinous-Osiris in white marble, now in the Vatican (see details below), was found in 1738/1739 (or perhaps 1740) on the estate of Liborio Michilli, which included part of the Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli. The findspot turned out to be the Serapeum of the Canopus, which was a feture of the villa complex. It was thought that the statue had been set up there as a pendant to the red marble version.

The armless and legless red marble statue became part of the Albani Collection until it was taken to Paris by Napoleon, along with many other artworks. After his demise it was purchased by Ludwig, crown prince of Bavaria (later Ludwig I), for the Egyptian Hall of his planned Glyptothek (sculpture museum) in Munich, which opened in 1830.

Ludwig commissioned the Danish neo-classicist sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), whose studio was on the Piazza Barberini, Rome, to restore the statue, using the Antinous-Osiris in the Vatican as a model. He added the missing left arm, right forearm and both legs from the thighs. Thorvaldsen had already restored the pedimental sculptures from the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina (see Niobe). After World War II Thorvalden's additions were removed and the statue was moved to its present location in the Museum of Egyptian Art.

Image source: Adolf Furtwängler, Illustrierter Katalog der Glyptothek König Ludwig's I zu München, No. 27, page 5 and plate 1. Königlich Hof-Buchdruckerei Kastner & Callwey Munich, 1907. At the Internet Archive.

The white marble statue of Antinous as Osiris in the Vatican:

Museo Gregoriano Egiziano (Gregorian Egyptian Museum), Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 22795. Parian marble. Height 243 cm (with plinth), width 77 cm, depth 79 cm, weight 670 kg. In 1742 Michilli gave it to Pope Benedict XIV, who donated it the newly-founded Capitoline Museums. In 1838 it was transferred to the new Gregorian Egyptian Museum. Several parts were restored by Filippo Valle. |

|

| |

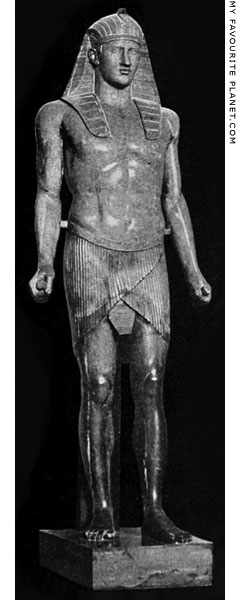

Egyptianizing statue of Antinous as the Egyptian god Osiris.

Marble, 2nd century AD. Found in 1843 at Marathon.

From one of the four entrances to the temple in the

Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods at Brexiza, which

stood on a man-made islet in the Mikro Elis (Small

Marsh) near the sea at Brexiza, southeast of

Marathon, Attica. It was built around 160 AD by

the wealthy Athenian Herodes Atticus who also

founded a cult for his young protegé Polydeukes.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Egyptian Collection. Inv. No. 1. |

|

|

|

| |

The Brexiza temple had four entrances in the form of Egyptian pylons, one at each of the cardinal points of the compass. Each entranceway was flanked by a statue of Isis (see the Herodes Atticus page) and one of Antinous as Osiris. Three of the Antinous statues have so far been found, the other two are now in the Marathon Archaeological Museum (see below).

It has been pointed out that the faces of these statues do not resemble other portraits of Antinous, and it has been suggested that they may represent one of the adopted sons of Herodes Atticus, perhaps Achilles or Polydeukes (see portraits of Polydeukes on the Herodes Atticus page).

A bust (Inv. No. 173) and the torso of a sitting statue of Antinous were discovered in 1977 and 1996 respectively, in the villa of Herodes Atticus at Eva, near Loukou, in the Peloponnese, where there was a heroon dedicated to Antinous. They are now in the nearby Archaeological Museum of Astros (currently not open to the public). |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

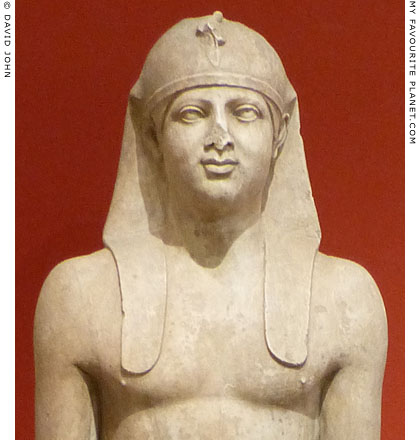

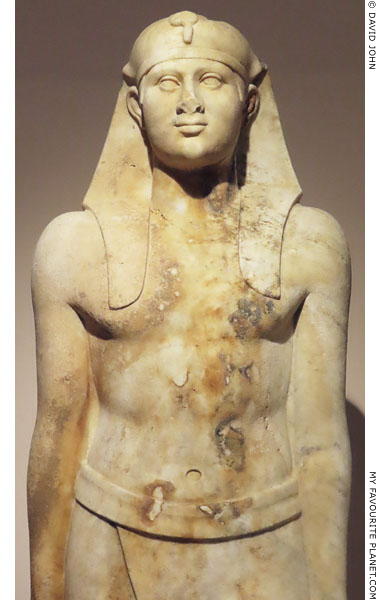

Larger than lifesize marble statue of Antinous-Osiris from the

west porch of the Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods at Brexiza.

Height 240 cm. Found in 1968 in the Egyptian sanctuary.

2nd century AD.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1. |

|

| |

|

|

|

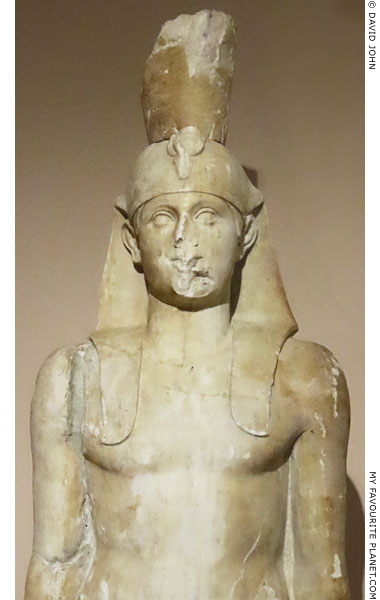

Larger than lifesize marble statue of Antinous-Osiris wearing the double crown of Upper

and Lower Egypt. From the north porch of the Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods at Brexiza.

2nd century AD.

Marathon Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

The "Antinous Braschi", a colossal marble statue

of Antinous as Dionysus-Osiris in the Vatican.

130-138 AD. Carrara marble. Height 335.2 cm.

Sala Rotonda, Museo Pio Clementino, Vatican Museums. Inv. No. 256.

The colossal marble statue was found almost intact in April 1793, during excavations by the Scottish painter, antiquarian and antiquities dealer Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798) at what is thought to have been the villa of Hadrian at Praeneste (today Palestrina), 35 kilometres east of Rome. It was restored 1793-1795 for Pope Pius VI (Giovanni Angelo Graf Braschi, 1717-1799) by the papal sculptor Giovanni Pierantoni (1742-1817). Pius presented it to his nephew Duke Luigi Braschi Onesti (1745-1816), who placed it in his unfinished Palazzo Braschi, Rome.

During the Napoleonic occupation of Rome, 1798-1802, the French occupied the Palazzo Braschi and confiscated Onesti's recently acquired antiquities with the intention of transporting them to Paris. However, the statue remained in Rome and was returned to Onesti in 1801. His son, Pio Braschi Onesti, sold it to Pope Gregory XVI in 1843, and it was exhibited in the Lateran Museum from 1844. In 1863 Pope Pius IX had it moved to the Museo Pio Clementino.

The restored figure appears more Dionysian than Osirian. He wears a crown of ivy leaves and berries, and a diadem over which may originally have been a uraeus (cobra), replaced by modern restorers with a lotus blossom (interpreted by some as a pine cone). The Dionysian attributes of the thyrsos and the cista (mystical chest) next to the left foot are also modern additions.

Pierantoni also restored the statue of Antinous now in the Lady Lever Art Gallery (see below).

Image source: Ernest H. Short, A history of sculpture, page 136. William Heinemann, London, 1907. At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

|

|

|

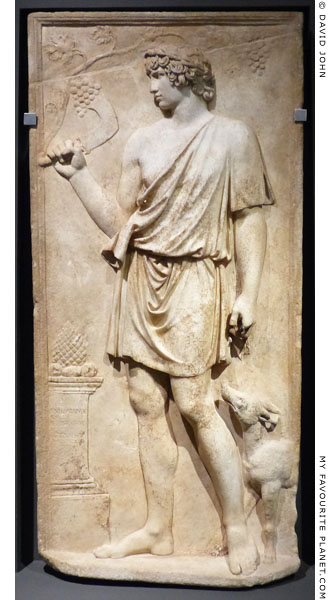

Marble relief showing Antinous as Silvanus, the Roman god of the woods, harvesting grapes.

130-138 AD. Found in 1907 in the ruins of a villa in a residential area

at Torre del Padiglione, between Lanuvio and Anzio. Pentelic marble.

Height 143 cm, width at top 69 cm, width at bottom 63 cm, depth 11 cm.

The figure wears a crown made of a pine branch and a short tunic, and holds a falx (sickle) in his

right hand. A dog stands on the right. On the left is an altar topped by a pine cone, and on the

side the signature of the artist Antonianos of Aphrodisias (see photo below) inscribed in Greek.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 374071. |

|

| |

Inscription in Greek on the side of the altar

on the relief of Antinous as Silvanus:

ANTωNIANOC AΦPOΔEICIEYC EΠOIEI

Antonianos of Aphrodisias made this.

Inscription SEG 43, 904. |

| |

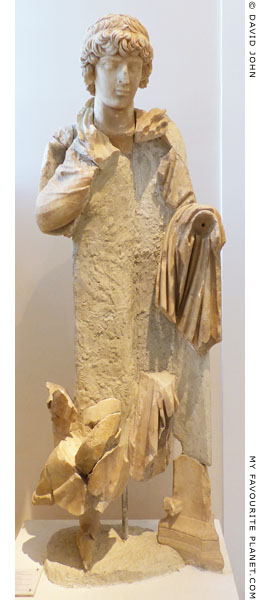

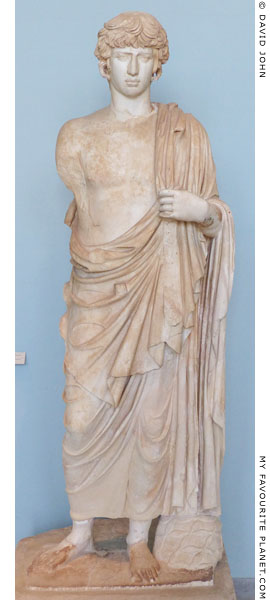

A fragmentary marble statue of Antinous as Androklos (Ἄνδροκλος),

the legendary or mythical Athenian founder and first king of Ephesus.

Part of a statue group, perhaps depicting the legend of Androklos

with his dog hunting a wild boar.

Found in 1927 in the Vedius Baths and Gymnasium complex, Ephesus.

138-161 AD (perhaps around 150 AD). Height of reconstructed fragments 185 cm.

Izmir Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 45.

Ephesian coins from the reigns of Hadrian (117-138 AD) to Gallienus (253-268 AD) show Androklos hunting a wild boar, a reference to the founding legend of Ephesus related by Athenaeus of Naucratis (see Ephesus gallery page 22). One of the earliest, from Hadrian's reign, shows a bust of Antinous with the inscription "Heros Antinoos" on the obverse side. The reverse shows a youthful Androklos standing in a heroic pose, naked apart from a chlamys (short cloak, as in the statue of Antinous above), in front of an olive tree, and the inscription "Ephesion Androklos". He holds a spear in his left hand and carries a dead boar in his right hand.

Coins from the mid 2nd to 3rd century show the head of the current emperor on the obverse side, and on the reverse a similar representation of Androklos, sometimes with a hunting dog. Others show Androklos hunting a boar either with a spear or on horseback, or standing next to the hero Koressos with both holding the dead boar.

Androklos is also shown on coins of other cities during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, standing to the right of the founder of that city (e.g. Alexander the Great for Alexandria and the hero Kyzikos for Kyzikos), either shaking hands or holding statuettes of their respective local deities (e.g the hero Pergamos with a statuette of Asklepios and Androklos with Artemis Ephesia). |

|

| |

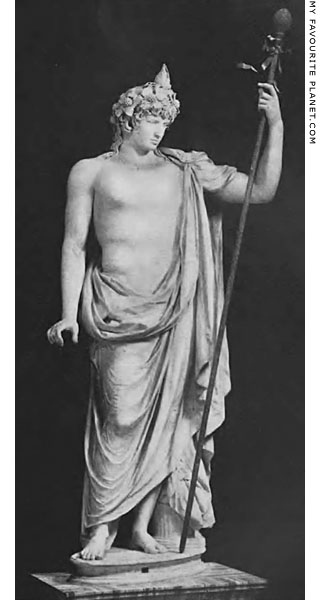

A marble statue of Antinous in the Lady Lever Art Gallery.

Said to have been found in Rome. Parian marble.

Height 232.5 cm, width 69 cm, depth 90.1 cm.

Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, England. Inv. No. LL 208.

Slightly larger than lifesize, the statue depicts Antinous as an athletic nude looking up at a wine cup, raised high in his right hand. He holds a jug in the lowered left hand by his side. His discarded garment is draped over a tree stump which acts as a prop for the marble figure. The cup and jug were added during the restoration around 1794-1796 by the sculptor Giovanni Pierantoni (1742-1817), who also restored the "Antinous Braschi" (see above). Other additions include: "the tip of the nose, both forearms, the lower half of left leg and four toes of the right foot" (Christie's catalogue, 1917, see below).

The restored figure has been interpreted as "Antinous as Ganymede", the youth abducted by Zeus, and often referred to as Zeus' cup-bearer. It has also been thought to depict Antinous as Hadrian's cup-bearer, one of the youths who poured wine at symposia (drinking feasts), a menial role with homoerotic connotations. Originally, the statue may have presented Antinous as a god, hero or victorious athlete.

Pierantoni sold the statue in 1796 to Thomas Hope (1769-1831), the Dutch-British merchant banker and antiquities collector, who was on a Grand Tour through Europe, Turkey and Egypt. It became part of the large art collection he kept at his house in Duchess Street, Cavendish Square, London. After Hope's death, it was moved to the family's country home, Deepdene House, near Dorking, Surrey. In 1917 the English soap manufacturer, philanthropist and politician, William Hesketh Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme (1851-1925) bought it at the two-day sale of Thomas Hope’s collection, paying the second highest price for a statue sold at the auction. It now stands with much of the Lever family's art collection in the excellent Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight, on the Wirral peninsula, near Liverpool.

See: www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ladylever/

Image source: Catalogue of the celebrated collection of Greek, Roman and Egyptian sculpture and ancient Greek vases, being a portion of the Hope Heirlooms, catalogue No. 251, page 136, plate XV. Christie, Manson and Woods, London, 1917. At the Internet Archive. The catalogue of the auction of the Hope collection at Christie's, London, 23-24 July 1917. |

|

| |

Marble head of Antinous.

Greek marble. 130-138 AD. Found 1869 in the sanctuary of the Magna

Mater (Campo della Magna Mater, Regio IV, Insula I), Ostia, near Rome.

Here Antinous wears a double-torse crown (or bust crown)

with reliefs of Emperor Nerva (or Trajan) and Hadrian, which

perhaps suggests that he is depicted as a priest of the Imperial cult.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 341.

For more information about bust crowns see Selçuk gallery 1, page 4. |

| |

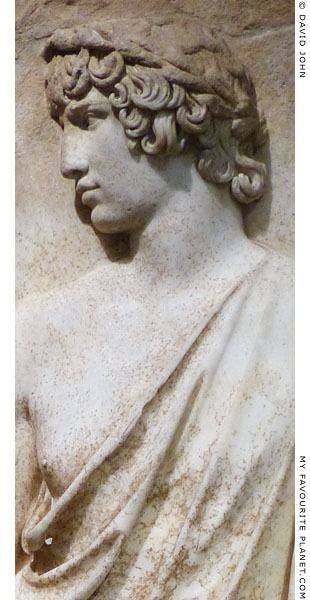

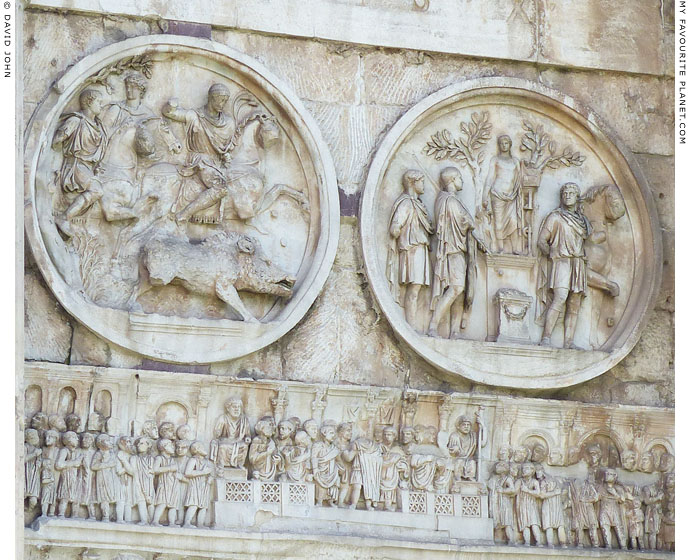

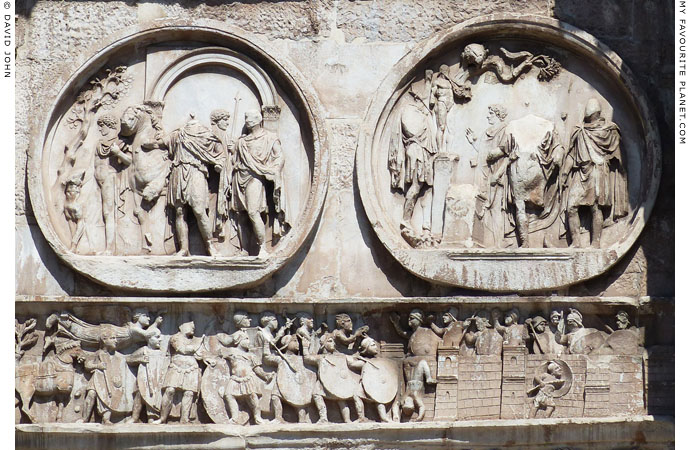

The pair of tondos on the left (east) side of the north face of the Arch of Constantine, Rome.

The tondo on the left shows three men on horseback hunting a boar. The central figure is

thought to be Antinous, and on the right is Hadrian, later resculpted to portray Constantine.

On the right-hand tondo, depicting three men sacrificing to Apollo, Hadrian's head has been

reworked to depict Licinius or Constantius I.

|

The Arch of Constantine, the largest ancient monumental gateway in Rome and perhaps the last to be built in the city, stands astride the Via Triumphalis (the Triumphal Way), in the Valley of the Colosseum, between the east side of the Palatine Hill and the Colosseum.

In 315/316 AD the Senate and people of Rome dedicated the triumphal arch to Emperor Constantine (reigned 306-337 AD) to celebrate his decennalia (ten years as emperor) and his victory over his rival emperor Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 AD. However, it has been argued that the arch itself may have been erected during the reign of an earlier emperor, perhaps Hadrian, Maxentius or even as early as Domitian (81-96 AD).

The archway is 21 metres high, 25.9 metres wide and 7.4 metres deep. The main central arch, 11.5 metres high and 6.5 metres wide, is flanked by two smaller lateral arches, each 7.4 metres high and 3.4 metres wide. The building is covered with reliefs, many taken from earlier monuments of the reigns of Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius.

Above each of the lateral arches, on both sides of the building, is a pair of marble tondos (or roundels) taken from an unknown monument of Emperor Hadrian, depicting scenes of hunting and sacrificing. The tondos are all around 2.4 metres in diameter. The tondo pairs are displayed on the archway as follows:

North face: left side, boar hunt, sacrifice to Apollo; right side, lion hunt, sacrifice to Hercules.

South face: left, departure for the hunt, sacrifice to Silvanus; right, bear hunt, sacrifice to Diana.

Many scholars are convinced that the central figure in the boar hunt scene is Antinous and that he may also be portrayed in other tondi. Although there appears to be no direct evidence for this, the head of the young man has been compared to other known portraits of Antinous. It is not known whether the scenes depict historical events or are allegorical, but Hadrian's alleged hunting exploits are mentioned in ancient literature, including a contemporary poem by the Alexandrian poet Pancrates in which Hadrian and Antinous hunt a lion in the Lybian desert. [26]

The relief below the pair of tondos above is part of the frieze from the time of Constantine that runs around the archway, depicting scenes of his victory over Maxentius and his acceptance as co-emperor by the people of Rome. In this scene, known as Oratio, he speaks to the citizens in the Forum after his victory. Unfortunately, the emperor has lost his head.