|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Attica > Athens > galleries > Acropolis |

|

| |

The northwest of the Acropolis from the Areopagus. The red colouring is caused by the setting sun. |

The north slope of the Acropolis

Part 1

The Klepsydra spring and the

caves of Pan, Zeus and Apollo |

| |

The sanctuaries at the foot of the north slope of the the Acropolis can be visited by walking along the Peripatos, the ancient circuit path around the rock (see next page). There is a separate entrance to the north slope on the west side (ask the ticket collectors at the main entrance for directions), or from above the Theatre of Dionysos on the east side.

The southern section of the Peripatos and the foot of the south slope is also connected directly from a path outside the entrance to the upper part of the Acropolis.

See a model of the Acropolis viewed from the north side on gallery page 2. |

|

|

| |

The west side of the Acropolis from the Areopagus hill to the north.

|

| In front of the Propylaia, the wide monumental gateway to the top of the rock, stands the Pedestal of Agrippa, and on a separate bastion to the right is the small Temple of Athena Nike. Below and to the left (east), the stone walls end and in the bare rock are ancient cave sanctuaries and the Klepsydra spring. |

|

|

| |

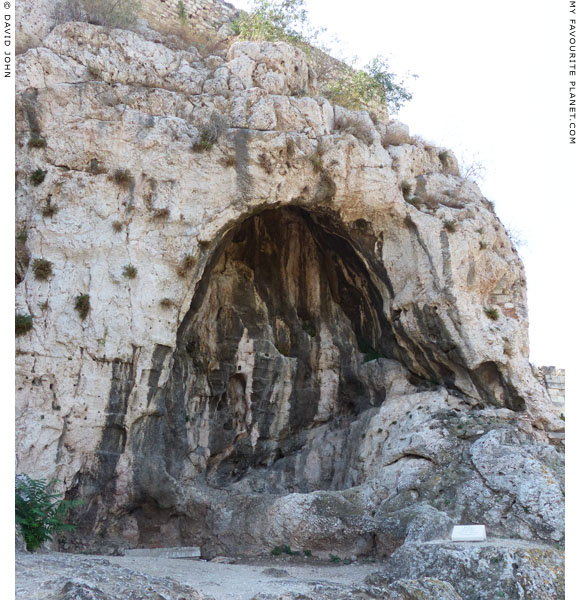

The northwest corner of the Acropolis. The large hole in the rock outcrop is known as

"Cave A". To the left of it is "Cave B", which housed the sanctuary of Zeus Olympios.

|

Archaeologists imaginatively named the group of shallow cave sanctuaries along the northwest face of the Acropolis, directly above the Klepsydra, caves A-D (from right to left, i.e. west to east) because of uncertainty as to which gods each was sacred.

It is not known to whom Cave A, which is not accessible, was dedicated. Cave B housed the sanctuary of Apollo Hypoakrais (Ἀπόλλωνι ὑπὸ Ἄκραις, Apollo beneath the edge of the rock; or Apollo Hypo Makrais, Ἀπόλλωνι ὑπὸ Μακραῖς, Apollo below the Long Rocks), and Cave C that of Zeus Olympios (or Zeus Astapaios). Cave D, the smallest, was dedicated to Pan. According to Herodotus, the worship of Pan was introduced to Athens from Arcadia in thanks for his aid against the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. [9]

"Pan, the dear son of Hermes, with his goat's feet

and two horns - a lover of merry noise."

The Homeric Hymn 19, to Pan. |

|

|

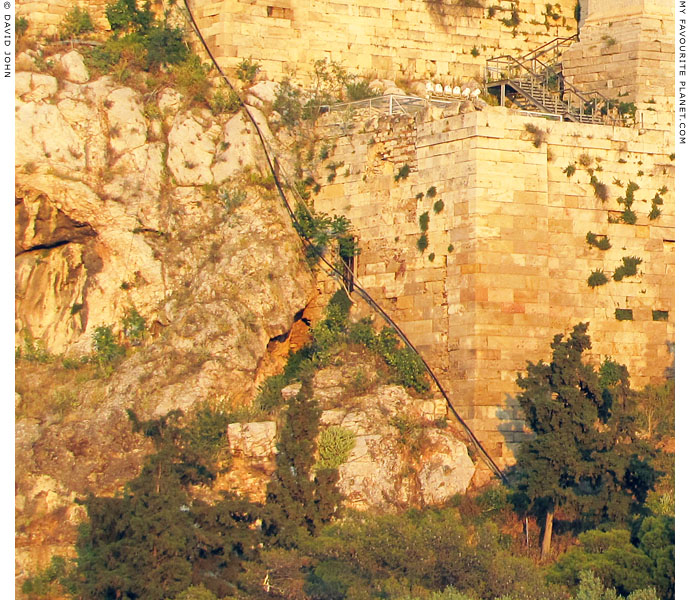

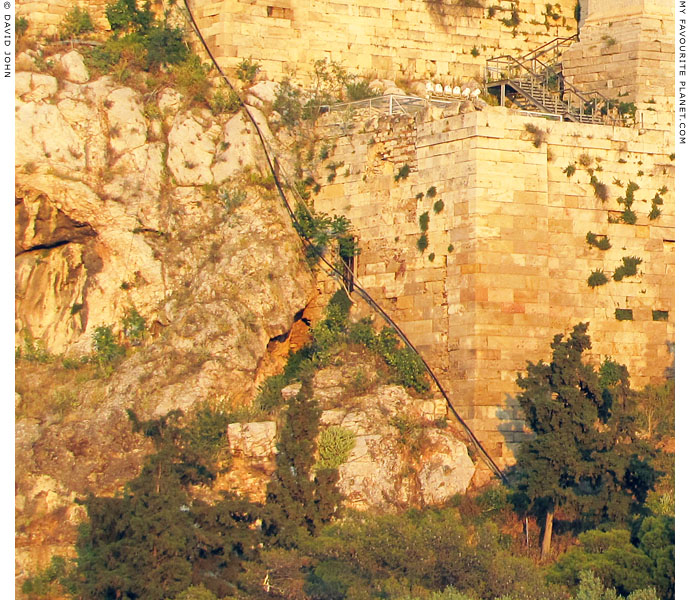

| |

Gateway to the Klepsydra spring from the terrace on which the Pedestal of Agrippa stands.

A stairway led from the terrace (see gallery page 9) down to the the gateway, which

is now walled up. Another stairway then led down from the gate to the Klepsydra.

The cable or pipe in front of the gate supplies the restoration workers on the Acropolis. |

| |

The Klepsydra

The spring and the ancient sanctuaries

on the north slope of the Acropolis |

| |

At the northwest corner of the Acropolis, just below the north hall of the Propylaia, a narrow Roman stairway leads down from the terrace on which the Pedestal of Agrippa stands to a small gate (now walled up), used to access the sacred cave containing the spring known as the Klepsydra (or Clepsydra, Greek κλεψύδρα), one of Athens' ancient sources of water. Its name literally means "stolen water" (also translated as "water thief"), apparently because the water occasionally disappeared, particularly during the summer months. However, some scholars now believe that the name actually signified "secretly" or "stealthily flowing" water because of its underground course. [1]

The Klepsydra stood at the junction of the Panathenaic Way (the 1050 metre long road which led from the Dipylon Gate, through the Agora to the Propylaia) and the Peripatos (the ancient circuit road around the Acropolis, see photos below), within the ancient defensive walls of the Acropolis (the Mycenaean "Pelargic Wall") so that it could be accessed during a siege. In ancient times it was reached by another stairway descending from the northeast side of the rock. Its water has been reported to be brackish (salty), and it is likely that during times of peace it was used for cleaning and purification purposes rather than drinking. [2]

It was one of three springs on the Acropolis created by rainwater seeping through the porous Cretaceous limestone which forms the top of the Acropolis hill, until it reaches the non-porous marls known as "Athens schist" beneath. Water pressure and erosion carved natural caves, clefts, reservoirs, channels and springs. [3] These springs, considered sacred by ancient Athenians, supplemented water supplied by wells and cisterns, as well as the Kiffisos and Ilissos streams which could only be relied on in winter.

The underground water was already being exploited in the Neolithic period (3500-3000 BC), during which 22 wells were dug in Athens. The Klepsydra cave is thought to have been discovered in the late 13th century BC when the area was cleared of rocks and rubble during the refortification of the Acropolis.

From at least Archaic times this spring was named Empedo (steadfast, continual) [4], after one of the Naiades (Ναϊάδες, from the Greek verb νάειν, naö, to flow) [5], divine fresh-water nymphs who were protectors of water supplies as well as of girls and maidens.

The worship of nymphs was widespread in Greece, and through myth and legend nymphs became associated with local places and people, often woven into the history and genealogies of tribes, villages and towns. Rituals of these cults involved nympholeptic possession and prophecy [6].

A poros boundary stone found in the ancient Agora of Athens, dated to the first half of 5th century BC, is inscribed "boundary of the sanctuary of the Nymphs". It is thought that the inscription referred to the Klepsydra. [7]

There were several caves and springs sacred to nymphs in Attica, one of the most famous of which was the Athenian Kallirroe (or Callirhoe; Καλλιρρόη, lovely flowing), to the south of the Acropolis, near the River Ilissos. Another spring dedicated to nymphs was on the south slope of the Acropolis, near the Asclepieion. |

See a plan of this corner of

the Acropolis and the stairs

to the Klepsydra below.

See more photos of this corner

of the Acropolis, including

the top of the stairway,

on gallery page 9. |

| |

See plans of the entrance to

the Acropolis, with the Beulé

Gate, the Propylaia, the Temple

of Athena Nike, the Pedestal

of Agrippa and the top of the

stairway to the Klepsydra,

on gallery page 10. |

| |

Athenian drachma coin showing

the north side of the Acropolis,

with the Parthenon, the colossal

statue of Athena Promachos,

the Propylaia, "the Pelasgian

stairway" and one of the cave

sanctuaries, thought to be the

Cave of Pan, in which the rustic

god is seen crouching. [8] |

| |

| |

The northwest slope of the Acropolis with the sacred caves of Pan, Zeus and

Apollo (see below) beneath the Propylaia. On the right is the gate of the

stairway from the platform of the Pedestal of Agrippa down to the Klepsydra. |

|

The spring appears to have become known as Klepsydra sometime after the Persian wars, and a fountain house and paved court (see photo below) were built around it between 470 and 460 BC, during the rebuilding of the Acropolis following destruction by the army of Xerxes I in 480-479 BC. From this time also this area of the Acropolis became more associated with the cults of the male deities Zeus, Apollo and Pan, whose sacred grottoes were above the spring.

The Greek historian Plutarch tells us that Marc Antony spent the winter in Athens before travelling to Syria to fight the Parthian King Hyrodes (37 BC). "When the time came for him to set out for the war, he took a garland from the sacred olive [of the Erechtheion], and, in obedience to some oracle, he filled a vessel with the water of the Clepsydra to carry along with him." [10]

During Roman times water from the spring was channelled to the Roman Agora where it was used to supply the water clock, also known as the Klepsydra, devised by Andronicus Cyrrhestes, which was housed in the Tower of the Winds. The name Klepsydra later became a general name for water clocks. [11]

The second century AD travel writer Pausanias described the way from the Propylaia: "On descending [from the Acropolis], not to the lower city, but to just beneath the Gateway, you see a fountain and near it a sanctuary of Apollo in a cave. It is here that Apollo is believed to have met Creusa, daughter of Erechtheus..." [12] The story of Apollo raping Kreousa (Κρέουσα) in this "laurel-covered" cave, where she later left their baby Ion (Ἴων, the founder of the Ionian Greeks) to die, before the god arranged for him to be saved, was told in the drama Ion by Euripides (probably written 414-412 BC), who is the only known ancient author to mention the name from which the Apollo's epiphet Hypo Makrais was taken.

Landslides in the 1st - 3rd centuries AD destroyed the fountain house and blocked the entrance, after which a well and vault were constructed.

The water from the spring was considered holy by early Christians, and the Chapel of Agioi Apostoloi (Holy Apostles) was built here during the Byzantine period. The Franks carried out repairs to the spring in the mid 13th century, but during the Turkish occupation in the 15-19th centuries it was abandoned. However, the water from the spring continued to flow down to the Roman Agora where it supplied water to the Fethiye Mosque, as Stuart and Revett reported when describing the nearby Tower of the Winds in the mid 18th century:

"For there is a spring which rises at the foot of the rock on which the Acropolis is built, somewhat before you arrive at the Propylaea, and supplies a current, of which indeed nobody drinks, for the water is brackish; but it is conveyed, partly under ground, and partly in earthen pipes which are supported by walls, to the principle Moschéa; where the Turks use it for those ablutions which they constantly perform whenever they begin their devotions." [13]

In 1822, during the Greek War of Independence, Greek forces besieged the Acropolis. It appears that the Turkish defenders had sufficient supplies of food but, not knowing about the Klepsydra, suffered from a lack of water.

When they finally surrendered, the story goes that the Greek archaeologist Kyriakos Pittakis (Κυριάκος Πιττάκης, 1798-1863), who was born in Athens and had taken an early interest in its history, showed the Greek leaders the location of the spring. They had the rubble cleared away and secured the water supply, and in September 1822 the Greek commander in chief, Odysseas Androutsos (Οδυσσέας Ανδρούτσος, 1788–1825) had the area fortified with walls which became known as "the Bastion of Odysseus" (see illustrations below). The bastion was built with parts of ancient monuments, which were rediscovered by archaeologists when it was dismantled in 1888.

Article: © David John, Athens and Berlin, 2007-2015. |

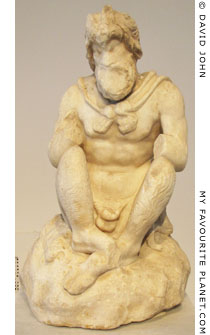

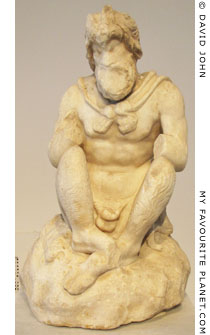

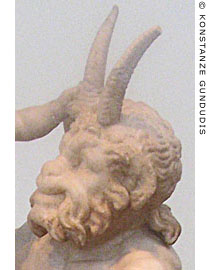

Statuette of Pan sitting cross

legged on a rock covered with

an animal pelt. Found at the

Olympieion, Athens, near which

is another cave of Pan, on the

Ilissos River. Pentelic marble.

2nd century BC, perhaps

a copy of a 4th century work.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 683. |

| |

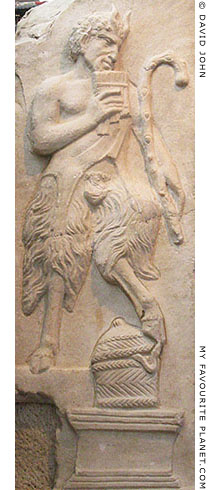

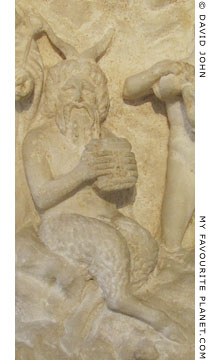

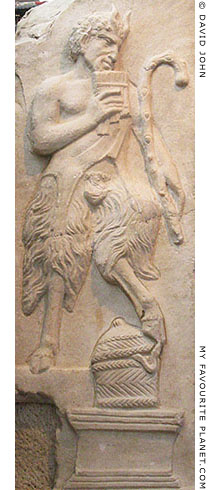

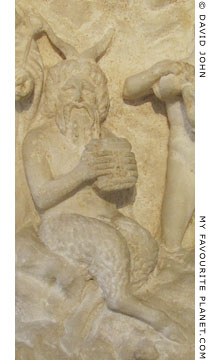

Relief of Pan, on the side of

the "Little Arch of Galerius",

Thessaloniki. Marble, Roman,

early 4th century AD.

Thessaloniki Archaeological

Museum. |

| |

|

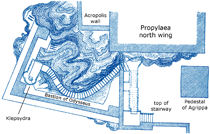

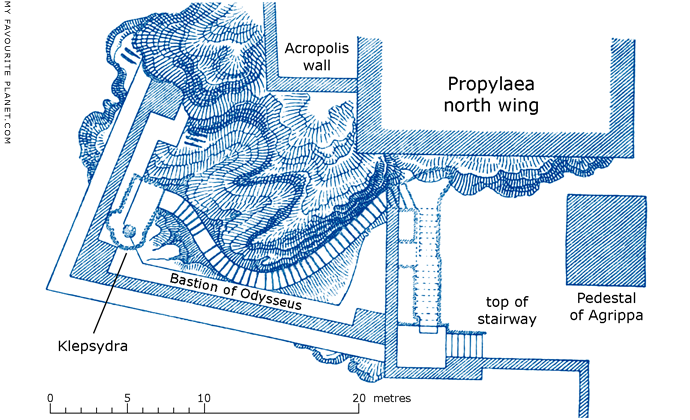

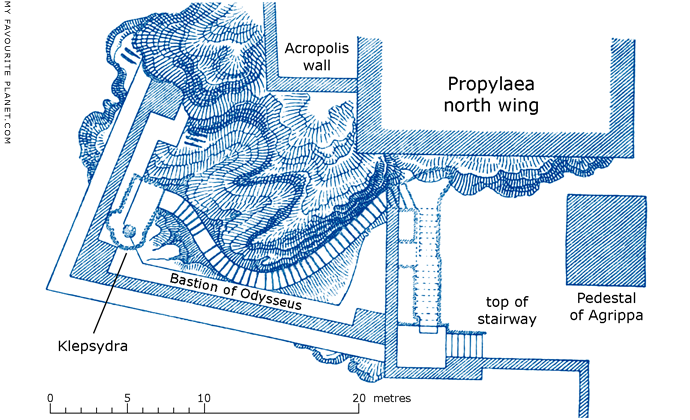

Plan of the northwest corner of the Acropolis and the stairway down to the Klepsydra spring.

Around the spring itself is the outline of the medieval Chapel of the Twelve Apostles (see below).

The fortification wall known as "Bastion of Odysseus" was built in September 1822

by the Greek general "Kapitani Odysseus" to protect the Klepsydra water supply.

After drawings by J. A. Kaupert, published in Adolf Boetticher, Die Akropolis von Athen: nach

den Berichten der Alten und den neusten Erforschungen. Verlag von Julius Springer, 1888. |

| |

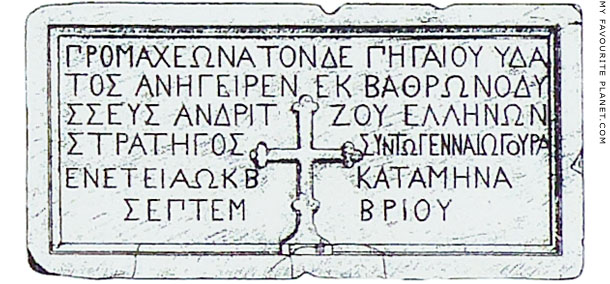

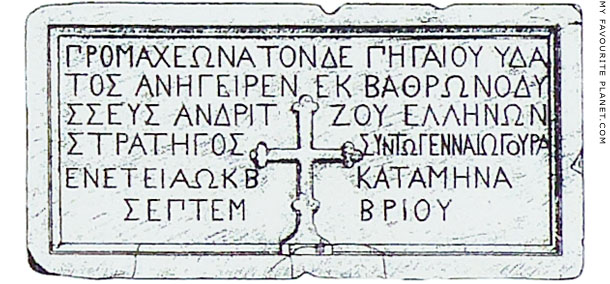

The inscription referring to the construction of the Bastion of Odysseus,

still in situ on the rock above the Chapel of the Holy Apostles.

The English clergyman and classical scholar Christopher Wordsworth

(1807-1885), who travelled through Greece 1832-1833, noted the

Greek inscription on a marble slab on the outside of the bastion:

ΠΡΟΜΑΧΕΩΝΑ ΤΟΝΔΕ ΠΗΓΑΙΟΥ ΥΔΑ

ΤΟΣ ΑΝΗΓΕΙΡΕΝ ΕΚ ΒΑΘΡΩΝ ΟΔΥΣΣΕΥΣ

ΑΝΔΡΙΤΖΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΩΝ ΣΤΡΑΤΗΓΟΣ

ΕΤΕΙ ΑΩΚΒ ΚΑΤΑ ΜΗΝΑ ΣΕΠΤΕΜΒΡΙΟΝ

"Odysseus, son of Andritzes, general of the Greeks, raised

from its foundations this bastion over a source of spring water,

in the year MDCCCXXII and the month of September." [14] |

| |

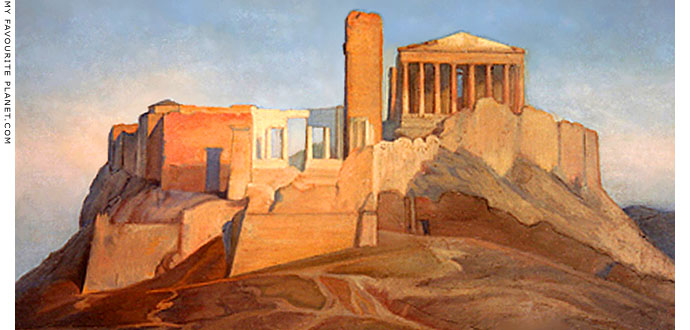

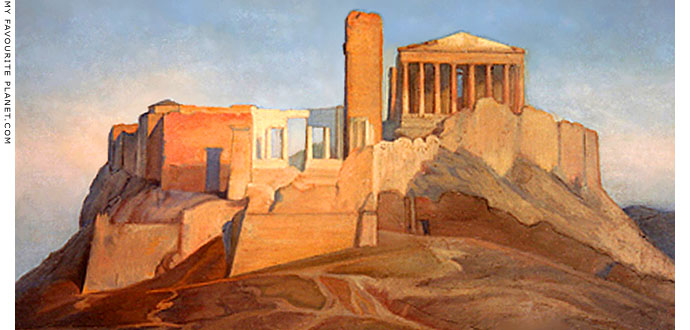

View of the Acropolis during the 1840s showing the

Bastion of Odysseus around the Klepsydra, bottom left.

Watercolour sketch by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867). |

|

Model of the Acropolis as it appeared in the 2nd century AD, viewed from the northwest.

The Klepsydra can be seen bottom right, below the caves of Pan, Zeus and Apollo.

Model in the Ancient Agora Museum, Athens. |

| |

A close-up of the above photo, with the the fountain house of the Klepsydra spring,

bottom right, below a rock. The Chapel of the Holy Apostles was later built over

this outcrop. In front of this is the area in which a paved courtyard was built

around 470-460 BC, during the Classical period.

|

The model shows the gate and stairway (far left) down the north slope of the Acropolis from near the Erechtheion, (see gallery page 5) but not the stairs from the terrace on which the Pedestal of Agrippa stands (right).

See the plan of the Propylaia (gallery page 10) showing the position of the Pedestal of Agrippa and the stairway down to the Klepsydra. |

|

|

| |

Drawing by Ernest Breton (1812-1875), made 1859 or earlier, of the Klepsydra spring,

over which the Byzantine Chapel of the Holy Apostles was built. The wall frescoes

were still visible, and at the far end stood a modern well which still exists. The faces of

the icons in the chapel are said to have been defaced during the Turkish occupation.

The chapel is currently being investigated by archaeologists [2], but is not open to the public. |

| |

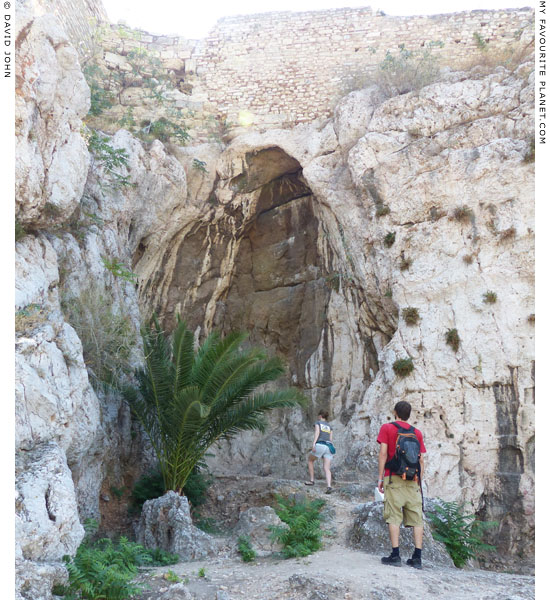

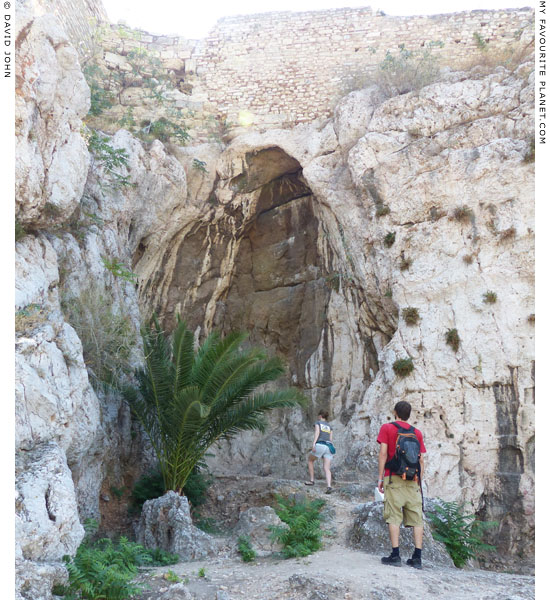

The entrance to the Chapel of the Holy Apostles at the foot of the north slope of the Acropolis,

surrounded by the remains of various defensive walls. At the top left, the Cave of Pan, one of

the cave sanctuaries above the Klepsydra. To the top right, the gate in the northwest wall

of the Acropolis, from which a stairway led down to the spring. The modern wooden stairs

are currently used by archaeologists and other experts working around the Klepsydra. |

| |

Greek archaeologists working at the paved court of the Klepsydra

(built around 470-460 BC) in August 2014. The enormous rock, right of

centre in the photo, masks the Chapel of the Holy Apostles behind it. |

| |

The Klepsydra court is paved with massive limestone blocks and bounded to the east by a wall. |

|

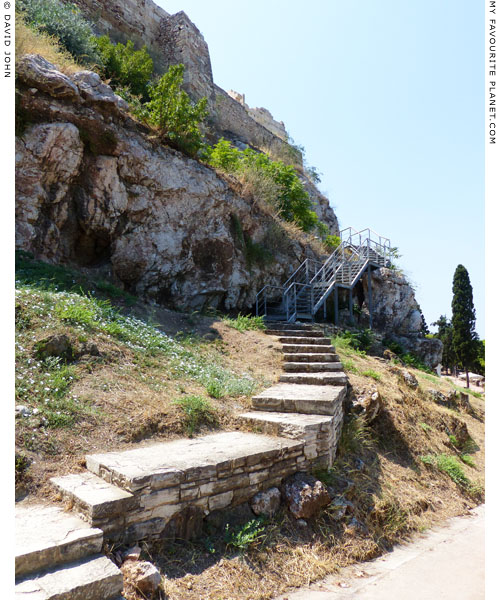

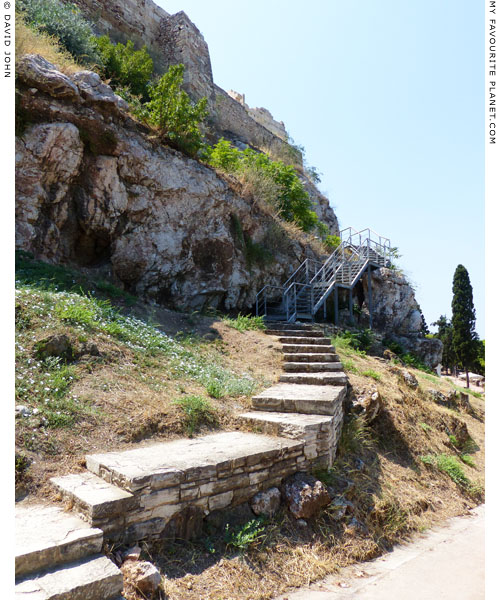

To the east of the Klepsydra, stone steps lead up from the Peripatos

to a modern metal stairway to the level of the cave sanctuaries. |

| |

The steps and stairway up to the cave sanctuaries from the

Peripatos. Like many of the areas on and around the Acropolis,

access to the sanctuaries are a challenge for the disabled. |

| |

Immediately at the top of the stairs are the entrances to the Cave of Pan,

(Cave D) which is in three parts. The east section was converted to a

chapel dedicated to Saint Athanasios (Άγιος Ἀθανάσιος) in the 5th century AD. |

| |

The remains of the Byzantine chapel of Saint Athanasios (Άγιος Ἀθανάσιος)

in the east section of the cave sanctuary of Pan. The floor is still level, and

built into the rock face to the right is what appears to be a stone water tank. |

| |

The Cave of Pan can still be entered by visitors, and a cleft in the rock on the other side

leads to the caves of Zeus and Apollo. Alternatively, there is a narrow path (right) to the

other caves. The white sacks on the ground contain cement used by restoration workers. |

| |

Inscribed marble votive relief thought to depict Hermes presenting

the infant Dionysus to a nymph in a cave, witnessed by other deities.

From Athens. Dedicated to Pan and the nymphs by Neoptolemos

of Melite, about 340-330 BC. Pentelic marble. Height 64.5 cm.

Museum of the Ancient Agora, Athens. Inv. No. I 7154.

Exhibited in the lower portico (ground floor) of the

Stoa of Attalus, in which the museum is housed.

|

Excavated in 1970 south of the Athenian Agora, in the remains of a Late Roman house on the north slope of the Areopagus. It is possibly from the Cave of Pan.

The relief is thought to have been deliberately mutilated, perhaps by Christians. The faces and objects held by most of the ten figures are missing, making identification difficult. The scene has been described simply as "ten figures watching or participating in a sacrifice in a cave". However, it has also been interpreted as Hermes bringing the infant Dionysus to safety and into the care of a nymph (perhaps one of the Hyades or Ino). The figures have been identified (with some alternative identifications) by comparison with similar reliefs and other sculptures.

Zeus reclines on a rock above the other figures. Below him, from left to right: Persephone (Kore) standing; Dionysus seated, holding his thyrsos; Demeter standing (both arms missing), looking down at Dionysus; Hermes, holding the infant Dionysus in both arms, his left foot resting on a rock behind an altar so that his left knee can support the infant; a nymph facing him receives the infant; Apollo (or a nymph) seated, facing left; Artemis (or a nymph) stands behind him with her right arm raised; Pan sits below them with a wineskin. There may have been another figure, perhaps a nymph, on the broken right side of the relief.

The figures thought to be nymphs (including the supposed Apollo and Artemis) have been described as smaller in scale than the others. But the only figure who appears smaller is the supposed Hermes, who is half a head shorter than the female figure facing him. It seems unlikely that this figure could be the dedicator of the relief, as in such reliefs mortal worshippers are usually shown considerably smaller and separated from deities, usually standing on the edge of the scene (see, for example, reliefs on the Pan page).

Two of the few artworks to show a mortal among gods are the much later Apotheosis of Homer (3rd or 2nd century BC) and the so-called "Ikarios reliefs" (perhaps 2nd century BC).

The inscription on the lower border of the relief is a dedication by Neoptolemos, son of Antikles, of the Attic deme of Melite, thought to be the wealthy Athenian citizen known from literary sources and other inscriptions.

[Νεο]πτόλε[μος] [Ἀν]τικλέ[ους] [Με]λιτε[ὺς] [ἀν]έθη[κεν]

Inscription IG II² 4901. |

|

|

| |

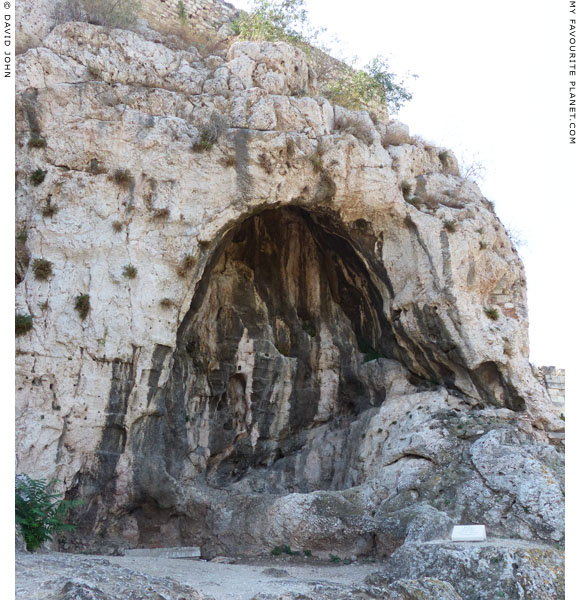

Cave C, the Sanctuary of Zeus Olympios (or Zeus Astapaios), the largest of

the three caves, between the Cave of Pan (Cave D) and the Cave of Apollo

(Cave B). Zeus was worshipped here from the 5th century BC. |

| |

The Cave of Apollo Hypoakrais (Apollo beneath the edge of the rock; or Apollo Hypo

Makrais, Apollo below the Long Rocks), the westernmost of the three cave sanctuaries.

|

Cave B, the Cave of Apollo is thought to have been in use from the 13th century BC (Mycenaean period). Above is part of the north wall of the Acropolis near the Propylaia. Apollo was worshipped here as Patroos, a patrimonial god. According to myth it was in this cave that Apollo raped Kreousa (Κρέουσα), daughter of Erechtheus, who consequently gave birth to Ion (Ἴων), the founder of the Ionian Greeks. Here also, the archons of Athens met at the end of their term of office and dedicated marble plaques carved with their names surrounded by reliefs of myrtle wreaths (see below).

Beyond this cave, to the right (west) is another large cave (Cave A), not accessible to the public and not yet identified, in front of which were rock-cut steps forming an exedra. |

|

|

| |

In and around the cave sanctuaries are numerous niches, cut in the rock for votive offerings,

images and inscriptions. This inscription to the left of the Cave of Apollo (Cave B), is a dedication

of around 276-282 AD "by archon Erennios Dexippos" (ἄρχων Ἑρέννιος Δέξιππ[ο]ς), believed

to be the Athenian statesman, general and historian Poplios Erennios Dexippos. [15]

Inscription IG II² 2931. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

| |

| |

Two of the inscribed marble dedicatory plaques dedicated to

Apollo Hypoakrais/Apollo Hypo Makrais from the Cave of Apollo.

| |

Dedication on left plaque: |

Dedication on right plaque: |

| |

Τιβ

Ἀντίστιος

Κινέας

ἐκ Κοίλης

Ἀπόλλωνι

ὑπ’ Ἄκραις

βασι-

λεύς. |

Tib[erius] Antistous Kineas

of Koile [dedicated this] to

Apollo Below the Heights

[Apolloni yp' Akrais],

as king [basileus]. |

ἀγαθῇ τύχῃ.

Inside the wreath:

Γ · Ἰούλιος

Μητρόδωρος Μαραθ

θεσμοθετήσας Ἀ-

πόλλωνι ὑπὸ Μακραῖς

ἀνέθηκεν. |

With good fortune.

G[aius] Julius Metrodoros

of Marath[on], having been

court president [Thesmothetes],

dedicated [this] to Apollo Below the

Long Rocks [Apolloni ypo Makrais]. |

| |

| |

Inscription IG II² 2894

Late 1st century AD. Pentelic marble.

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. ΕΜ 8124.

(Formerly in the Epigraphical Museum, Athens [16].) |

Inscription IG II² 2891

Mid 1st century AD. Pentelic marble.

Height 32 cm, length 25 cm, width 5 cm.

Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. ΕΜ 8123.

(Formerly in the Epigraphical Museum, Athens.) |

| |

Cave B was identified as that of Apollo in 1897 by Greek archaeologist Panagiotis Kavvadias (Παναγιώτης Καββαδίας, 1850-1928), who discovered 10 of the inscribed votive plaques, including the two shown above. Around 68 similar plaques, dating from the Roman period, mid 1st century BC - 3rd century AD, have so far been found in the area of the caves as well as around the Acropolis and Agora. Many fit the niches cut in the cave's walls. Around half the plaques are dedicated to Apollo Hypoakrais and the rest to Apollo Hypo Makrais. All the dedications are by one or more Athenian archons (the eponymous archon, the basileus, the polemarch, the six thesmothetai, or their secretary), either as individuals or a group, inscribed within reliefs of myrtle wreaths, some fastened at the bottom by two snakes. [17]

Image source: Panagiotis Kavvadias (Παναγιώτης Καββαδίας, 1850-1928), Τοπῦγραφικὰ Ἀθηνῶν κατὰ τὰς περὶ τὴν Ἀκρόπολιν ἀνασκαφάς, columns 1-32 and Pinax (plate) 4, and Ἐπιγραφαὶ ἀναθηματικαὶ τῷ Ἀπόλλωνι ὑπὸ Μακραῖς, columns 87-92. In: Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς, 1897. Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία (Archaiologike Ephemeris, journal of the Archaeological Society of Athens). Athens, 1898. 1896 and 1897 editions of the journal in a single volume at the Internet Archive. Pinax 4 is on page 285 of 308. |

|

| |

A votive relief depicting Pan, Apollo, Hermes, three Nymphs and a group of six adorants.

Found in 1900 at the caves of Apollo and Pan on the north slope of the Acropolis.

2nd century BC. Height 38 cm, width 73 cm, thickness 7 cm.

New Acropolis Museum, Athens. Inv. No. NAMA 1966.

Previously in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens [see note 16].

|

The long rectangular relief is in the form of a naiskos (ναΐσκος, small temple) with a Doric column at either end. On the left a small figure of Pan, wearing a cloak and facing right, plays the syrinx (pan pipes). In front of him Apollo reclines on a large rock, his right hand resting on his the top of his head, his left forearm and hand resting on a kithara (κιθάρα, concert lyre). He is naked apart from a himation (cloak) covering his groin and legs. Apollo is shown in this pose, though normally standing naked and holding a bow in his left hand, in statues of the type known as the Lycean Apollo or the Apollo Lyceus (Ἀπόλλων Λύκειος, Apollon Lykeios). The original of the type, which has been attributed by some scholars to Praxiteles and by some others to Euphranor, was displayed in the Athenian Lykeion (Lyceum gymnasium), where Aristotle established his Peripatetic school of philosophy. Some statues also show Dionysus in this pose (see examples on the Dionysus page).

To the right of Apollo, and shown at the same scale, a young, unbearded Hermes stands frontally, his head turned towards his half-brother. He wears only a cloak which hangs down his back from his shoulders. His left arm is bent, with the hand behind his back. In his right arm he cradles his kerykeion (κηρύκειον, herald's staff or wand; known in Latin as caduceus), and he has winged ankles. His right forearm rests on his raised right thigh, as his right foot rests on a large rock, which is either in front of or part of the rock on which Apollo lies.

To the right three Nymphs stand or dance in a row holding hands. Each has her head turned to face her neighbour, and wears a high-girdled, sleeveless chiton. In front of middle Nymph is a circular altar or well-head, and she actually appears to be standing in it, or appearing from it. On the far right of the stele stands a group of six worshippers, facing left towards the deities. Five are shown standing together in a tight group (one head is not visible in the photo because of the deep shadow cast by the column), while the sixth, perhaps their leader, a short-haired man dressed in a short chiton and a himation, raises his right hand in adoration. These figures probably represent those who dedicated the relief.

Image source: J. N. Svoronos (Ioannis Nikolaou Svoronos, Iωάννης Ν. Σβορώνος, 1863-1922), Das Athener Nationalmuseum, German edition by W. Barth, Textband 3, No. 341. Inv. No. 1966, page 634; and Tafelband 2, Tafel 136. Elefthouradakis Verlagsgesellschaft, Athens, 1937. |

|

| |

The north side of the Acropolis, viewed from the Psyri district of central Athens. |

| |

Acropolis

north slope

part 1 |

Notes, references and links |

|

|

Marble votive relief dedicated to the nymphs, about 330 BC.

Found in the Cave of the Nymphs, Mount Penteli, Attica.

Figures set in a cave, from left to right: three nymphs; Hermes wearing a chlamys

and holding his caduceus; Pan holding his syrinx (pan pipes); a nude youth pouring

wine into the kantharos held by Agathemeros, the dedicator of the relief.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 4466.

The name of Agathemeros is known by the separate base of the relief, Inv. No. 4466a.

See the photo on the Pan page of the MFP People section.

|

1 and 4. Empedo

From empedos (ἔμπεδος), meaning "firmly set", hence "in the ground"; and by extension, "steadfast", "continual".

See: Jennifer Lynn Larson, Greek nymphs: myth, cult, lore. Oxford University Press, 2001. Preview at Google Books.

Despite the connotations of unreliability associated with the later name Klepsydra, the American archaeologist Arthur Wellesley Parsons, who excavated the spring from 1937 to 1940, was of the opinion that it was indeed a steadfast and reliable source of water.

See: Arthur W. Parsons, Klepsydra and the Paved Court of the Pythion. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Vol. 12, No. 3, The American Excavations in the Athenian Agora: Twenty-Fourth Report (July - September 1943), pages 191-267. At Jstor.

2. In August 2014 I spoke with one of the Greek archaeologists working at the Klepsydra. She told me that during the Spring a geologist had investigated the area around the Klepsydra and the well in the Chapel of the Holy Apostles, and had tasted the water. He reported that it tasted sweet.

3. See: Michael and Reynold Higgins, A Geological Companion to Greece and the Aegean. Duckworth and Cornell University Press (out of print). Sample chapter: Chapter 3, Geology of Athens

5. Daniel Ogden, A Companion to Greek Religion. John Wiley and Sons, 2010. At Googlebooks.

6. The worship of nymphs

See:

W. R. Connor, Seized by the nymphs: nympholepsy and symbolic expression in Classical Greece. Classical Antiquity, Volume 7, No. 2, October 1988.

Jennifer Lynn Larson, Greek nymphs: myth, cult, lore. Oxford University Press, 2001. Preview at Googlebooks.

Nadine Pierce, The placement of the sacred caves in Attica, Greece. MA thesis, 2006. Open Access Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5356. McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

7. Nymph sanctuary boundary stone

The fragment of the horos (boundary marker), made of poros stone, was found built into the wall of a modern (late Turkish period) house, northeast of the Temple of Ares, "Section P" of the ancient Agora of Athens, on 23 April 23 1937. It has been dated to circa 475-450 BC. The inscription has led scholars to believe it marked the boundary of the Klepsydra spring as a sanctuary of the nymph Empedo.

The three-line inscription on the stone reads:

[Ν]υνφα

[ί]ο ℎιερο͂

ℎόρος

(Nymphaio sanctuary boundary)

Inscription: IG I³ 1063 (= SEG 10.357; = Agora XIX H3)

The stone is now in the Agora Museum, in the Stoa of Attalos.

Invoice No. I 4773.

Height 26.1 cm; width 36.5 cm.; thickness 22.1 cm.

Height of letters circa 5.4 cm.

See:

Benjamin D. Meritt (1899-1989), Greek inscriptions, Hesperia Vol. 10, No. 1, The American Excavations in the Athenian Agora: Nineteenth Report (Jan. - Mar., 1941), pages 38-64. American School of Classical Studies at Athens. At jstor.

Gerald V. Lalonde, Horoi of sanctuaries (H1-H24), page 22, in The Athenian Agora, Volume XIX: Inscriptions. American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1991. At jstor.

Arthur W. Parsons, Klepsydra and the Paved Court of the Pythion. Hesperia, Vol. 12, No. 3, pages 191-267 (see note 1 above).

Walther Judeich (1859-1942), Topographie von Athen (2nd edition), page 302. Beck, Munich, 1931. |

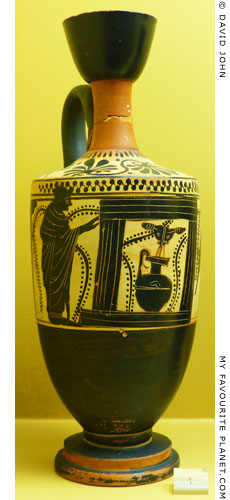

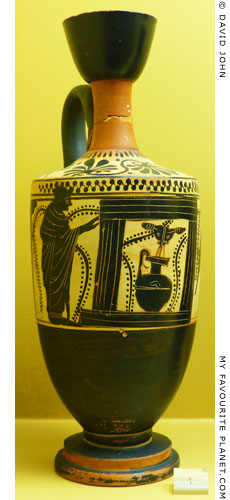

Attic white-ground, black-figure

lekythos, attributed to the

Gela Painter, with a fountain

scene. From the Ancient

Agora, Athens. Circa 500 BC.

Height 26.5 cm.

A man draped in a himation

waits for his large hydria to be

filled with water from a spout

in the form of a lion's head in

a Π-shaped fountain house.

Agora Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. P 24106. |

| |

Odos Klepsydras (Οδός Κλεψυδρας),

a steep narrow street in the

Anafiotika district on the north

slope of the Acropolis. The street

and the name are modern. |

| |

|

8. Athenian medallion showing the Acropolis from the north

"Pl. X. Médaille du cabinet de Paris, amplifiée.

Elle montre l'Acropole avec la grotte de Pan, l'escalier pélasgique, les Propylées, la Minerve-promachos et le Parthenon."

Émile-Louis Burnouf (1821-1907), former director of l’École française d’archéologie d’Athènes, La ville et l'Acropole d'Athènes aux diverses époques, Planche X. Maisonneuve et Co., Paris, 1877.

There are examples of this coin type in le Cabinet des médailles, Paris, and the British Museum. Those in the British Museum are not on display, but one is described on its website:

Alloy coin minted in Athens during the Roman Provincial period.

Topographic representation of Acropolis (Athens).

Weight: 8.06 grammes

Museum number: TC,p130.79.Ath

See britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/...

They are also described and illustrated in a British Museum catalogue:

"Obverse: Head of Athena r., wearing crested Corinthian helmet.

Reverse: Northern view of the rock of the Acropolis, on the summit of which are, l., the Parthenon, and r. the Propylaea, with the statue of Athena Parthenos* between them; a flight of steps leads up to the Propylaea: in the side of the rock is the grotto of Pan, in which, a seated figure of Pan.

* See K. Lange, Arch, Zeit., N.F. xiv. p. 199. From the prominence given to the flight of steps we may infer that this type was intended to commemorate the paving of the staircase with white marble in the reign of Caius [Augustus]. (C.I.A. iii. 1284, F)."

Barclay V. Head, Reginald Stuart Poole (editor), A Catalogue of the Greek coins in the British Museum: Attica, Megaris, Aegina, 805, page 110; Plate XIX, 6 and 7. British Museum Dept. of Coins and Medals, 1888. At the Internet Archive.

The coin type is mentioned by several authors, including James Stuart, Jean Jacques Barthélemy, Martin William Leake, Peter Oluf Bröndsted, Christopher Wordsworth and Taylor Combe.

Some describe the stairway as that between the Acropolis and the Klepsydra, while others believe it represents the great stairway to the Propylaia built during the Roman Imperial period.

9. The Cave of Pan beneath the Acropolis

Herodotus tells us that the legendary runner Pheidippides (Φειδιππίδης) was sent by the Athenians to ask the Spartans for their help against the invading army of Persian king Darius I before the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. On his two-day journey the professional messenger met the ancient rustic god Pan who wanted to know why the Athenians had forgotten him. After their victory they dedicated the shrine in the shallow cave next to that of Apollo.

"First of all, while they were still in the city, the generals sent off to Sparta a herald, namely Pheidippides, an Athenian, and for the rest a runner of long day-courses and one who practised this as his profession.

With this man, as Pheidippides himself said and as he made report to the Athenians, Pan chanced to meet by Mount Parthenion, which is above Tegea; and calling aloud the name of Pheidippides, Pan bade him report to the Athenians and ask for what reason they had no care of him, though he was well disposed to the Athenians and had been serviceable to them on many occasions before that time, and would be so also yet again.

Believing that this tale was true, the Athenians, when their affairs had been now prosperously settled, established under the Acropolis a temple of Pan; and in consequence of this message they propitiate him with sacrifice offered every year and with a torch race."

Herodotus, Histories, Book VI, 105, translated by G. C. Macaulay.

MacMillan and Co., London and New York, 1890. At Project Gutenberg.

Pausanias relates a slightly different version of the legend, and calls the runner Philippides (Φιλιππίδης).

"When the Persians had landed in Attica Philippides was sent to carry the tidings to Lacedaemon. On his return he said that the Lacedaemonians had postponed their departure, because it was their custom not to go out to fight before the moon was full. Philippides went on to say that near Mount Parthenius he had been met by Pan, who told him that he was friendly to the Athenians and would come to Marathon to fight for them. This deity, then, has been honored for this announcement."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 28, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Pausanias also informs us that in his day (mid second century AD) the Greeks believed the meeting between Pan and the Athenian runner took place near Mount Parthenios (ὄρος τὸ Παρθένιον) in the territory of Tegea (Τεγέα), Arcadia, in the Peloponnese.

"At this point begins Mount Parthenius. On it is shown a sacred enclosure of Telephus, where it is said that he was exposed when a child and was suckled by a deer. A little farther on is a sanctuary of Pan, where Athenians and Tegeans agree that he appeared to Philippides and conversed with him."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 54, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

Another sanctuary of Pan was founded after the Battle of Marathon, in the Cave of Pan at Oinoe near Marathon itself.

10. Plutarch, Parallel Lives: Antony at MIT Internet Classics Archive. |

| |

Another drawing of an Athenian

coin showing the Acropolis from

the north: the Parthenon, the

statue of Athena Promachos and

the Cave of Pan. British Museum.

Source: Christopher Wordsworth,

Athens and Attica: notes of a tour,

page 68. John Murray, London, 1855

(3rd edition). At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Detail of the votive relief in the

photo above, showing Pan with

his syrinx (Pan pipes). Around

330 BC. From the Cave of the

Nymphs, Mount Penteli, Attica.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 4466. |

| |

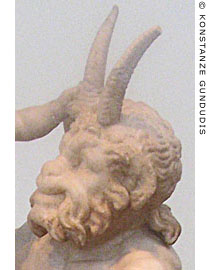

The goat-god Pan from a

statue group of Aphrodite,

Eros and Pan from Delos.

Circa 100 BC. Parian marble.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 3335.

Photo: © Konstanze Gundudis |

| |

| |

The Sanctuary of Pan on Apostolou Pavlou Street, at the foot of the Hill of the Pnyx,

near the Fountain of the Pnyx (previously erroneously identified as the Kallirroe spring).

On the wall of the underground cave chamber is a relief depicting Pan seated,

a naked nymph and a dog, chiselled directly into the rock. In front of the cave

is part of a Roman period floor mosaic (left). This sanctuary was not mentioned

by ancient authors, and before its discovery in 2002 it was unknown. |

| |

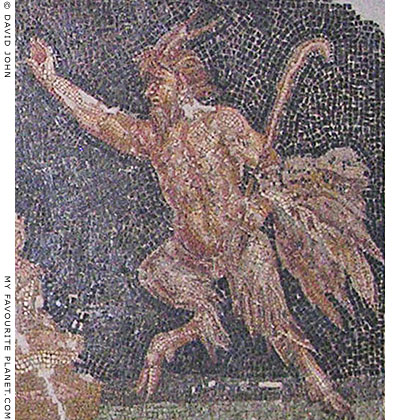

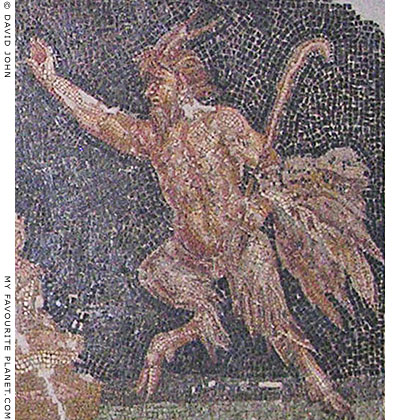

Pan on a floor mosaic from Ephesus.

Izmir Archaeological Museum, Turkey.

More information about this mosaic on Selçuk gallery 2. |

|

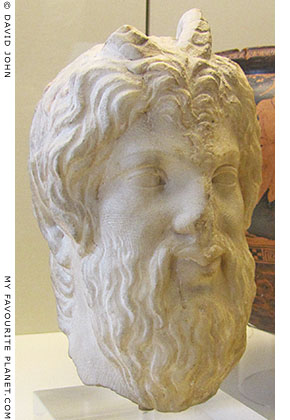

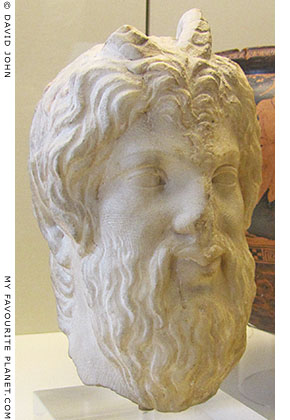

Marble head of Pan.

Made in Athens around 440-430 BC.

Said to be from Koropi (Κορωπί),

east of Mount Hymettos, Attica.

British Museum. GR 1931. 6-15. 1. |

|

|

11. Klepsydra as water clock

There were other springs called Klepsydra in Greece, for example at Messene in the Peloponnese. How and when the name was applied to water clocks seems to be another history mystery yet to be unravelled. Water clocks were known since at least the middle of the second millennium BC, and an Egyptian alabaster device from the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak has been dated to the reign of Amenhotep III, around 1388-1350 BC. Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Inv. No. JE 37525.

"Before the advent of the mechanical clock in the 13th century, our ancestors depended upon both sun dials and water clocks for the telling of time. Sun dials are still well known. Water clocks are far less so and yet also have an intriguing history. They were developed as a complement to systems for telling time by the sun and the stars. They could function indoors and in cloudy weather when sun dials were useless. An inscription sometimes used on sun dials

'I tell none but the sunny hours'

is both a cheerful harbinger of good weather and an admission of weakness. Sun dials were surely more practical in sunny Egypt than in the cloudy climes of northern Europe."

John S. McNown, When time flowed: The story of the clepsydra. In: La Houille Blanche - Revue internationale de l'eau, Numéro 5, Août 1976, pages 347-353. Société Hydrotechnique de France, Paris. At Édition Diffusion Presse Sciences (EDP Sciences).

Water clocks could also measure the time at night, and the Karnak clock, which is estimated to have been designed to run for 12 hours, is inscribed with the length of night during the various seasons.

In Greece water clocks were already in use by the Classical period. A simple water-powered time-keeper, also known as a klepsydra, which worked on the same principle as an hour-glass, was used in Athenian law courts and political assemblies to limit the length of speeches. Two ceramic vessels were placed one above the other. The upper beaker had a hole near its base so that water trickled into the lower one; when all the water had run out, time was up (see photo, right). The beaker also has a hole at the top to prevent over-filling and cheating.

See:

Suzanne Young, An Athenian clepsydra. In: Hesperia, Volume 8, Issue 3, 1939. pages 274-284. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA).

Nikoletta Saraga, The Stoa of Attalos, the Museum of the Ancient Agora. Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the Archaeological Reciepts Fund, Athens, 2011. www tap.gr

In the late 360s BC the Athenian orator Demosthenes wrote an oration for a plaintiff in a private law case against Spoudias (see Demeter and Persephone part 1). At the end of his final plea the plaintiff is made to complain of the short amount of time allowed to him to present his case by the water clock.

"For you all know the facts of the case, unless perhaps I have omitted something, since I have been forced to speak with but scant water in the water-clock."

Demosthenes, Oration No. 41, Against Spoudias, section 30. In: Demosthenes, Private orations, Volume 2 (Orations 41-49), pages 24-25. In ancient Greek with an English translation by Augustus Taber Murray. Loeb Classical Library L 346 (actually volume 5 of 7 of the orations of Demosthenes). Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1939. At the Internet Archive.

Philostratus "the Athenian" (circa 160-249 AD) wrote that the wealthy Athenian Sophist philosopher Herodes Atticus held dinners with a select group of his pupils known as the Clepsydrion (Κλεψυδρίον), during which he would give a lecture that lasted for the time limited by a water clock:

"Now the Clepsydrion was conducted in the following manner. After the general lecture which was open to all, ten of the pupils of Herodes, that is to say those who were proved worthy of a reward for excellence, used to dine for a period limited by a water-clock [κλεψύδραν] timed to last through a hundred verses. And these verses Herodes used to expound with copious comments, nor would he allow any applause from his hearers, but was wholly intent on what he was saying."

Philostratus and Eunapius; The lives of the Sophists, Philostratus, Book II, chapter 10 (section 585), pages 222-223. In ancient Greek and English, translated by William Cave Wright. Loeb Classical Library. Heinemann, London and G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1922. At the Internet Archive.

12. Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book I, chapter 28, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Since Pausanias refers to a fountain, the fountain house may have been still standing when he visited Athens.

Further information about Pausanias in the PEOPLE section.

13. James Stuart, Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume 1,

Chapter 3, Of the Octagon Tower of Andronicus Cyrrhestes, page 15. John Haberkorn, London, 1762. At the Internet Archive.

For more about Stuart and Revett and their study of the ancient monuments in Athens, 1751-1753, see Acropolis gallery pages 11, 12 and 35. |

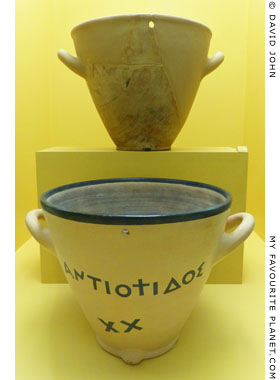

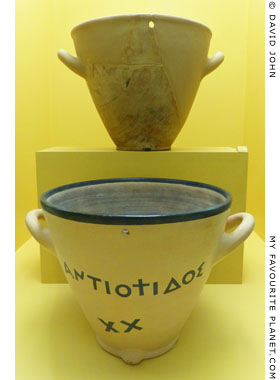

A klepsydra water clock reconstructed

from a late 5th century BC ceramic

original (top beaker), found in the

Athenian Agora. The inscriptions

"ANTIO..." and "XX" signify that it

belonged to the Antiochis tribe. It

had a capacity of 2 choai (6.4 litres)

and took 6 minutes to empty. This

was the time allowed for litigants in

a law court to deliver their speeches.

Such klepsydras were used in Athens

from the end of the 5th century

to the end of the 4th century BC.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. P 2084. |

| |

The Horologion of Andronikos, also known

as the Tower of the Winds or Aerides

(Blowing Winds) in the Roman Agora,

Athens. Designed by the architect and

astronomer Andronikos of Kyrrhos in

Macedonia, in the Late Hellenistic period,

possibly the late 2nd century BC. |

| |

| |

14. Christopher Wordsworth on the Bastion of Odysseus

The Reverend Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885) was from a family of Anglican clergymen and classical scholars. He was a nephew of the poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850), whose memoirs he edited and published in 1851.

After completing his studies at Cambridge University, he travelled through Greece 1832-1833, where he discovered the Oracle of Zeus at Dodona (1832), and was the first Englishman to be introduced to the new King Otto.

He wrote a number of books on ancient history, archaeology and epigraphy, most notably Greece, pictoral, descriptive, and historical (London, 1839).

He also wrote poetry, hymns and works on the history of Christiantiy and The Bible, including editions of the Greek New Testament and the Old Testament. He went on to achieve a number of academic and clerical positions, becoming Headmaster of Harrow public school, Archdeacon of Westminster and finally Bishop of Lincoln.

Christopher Wordsworth, Athens and Attica: a journal of a residence there. John Murray, London. Second edition, 1837, pages 84-86. At Heidelberg University Library.

The inscription appears on page 85. The date 1822 is written in ancient Greek numerals "ΑΩΚΒ": Α=1 (for 1000), Ω=800, Κ=20, Β=2.

It is typical of Wordsworth's style that he transcribed the ancient Greek numbering into Latin rather than modern Arabic numerals. Like many of his contemporaries, he continually used such archaisms, for example referring to Athena as Minerva.

The date of the rediscovery of the Klepsydra is given as 1828 on page 84. This is a printing error which does not appear in the first edition. In the second edition he adds in a footnote:

"M. Pittakys, the Athenian topographer of Athens, claims the honour of this discovery. Athènes, p. 155."

The credit seems grudgingly given, and from Wordworth's other references to Pittakis he appears skeptical of the Greek archaeologist's claims.

Pittakis' own account of the Klepsydra can be found in:

Kyriakos S. Pittakys, L'ancienne Athènes, ou La description des antiquités d'Athènes et de ses environs. M. E. Antoniades, Athens, 1835. At the Internet Archive.

Read more about Pittakis and his involvement in archaeology and restoration at the Acropolis on gallery page 12.

15. Erennios Dexippos

The Athenian statesman, general and historian Poplios Erennios Dexippos (Πόπλιος Ἑρέννιος Δέξιππος; Latin name Publius Herennius Dexippus; circa 210-273 AD), son of Poplios Erennios Ptolemaios (Πόπλιος Ἑρέννιος Πτολεμαῖος), was born in the Attic Deme of Hermos. He was a hereditary priest of the Kerykes (Κήρυκες) family, who with the Eumolpidai (Εὐμολπίδαι) family administered the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Some details of his family and career are known from other inscriptions found in Athens, particularly two inscribed statue bases: IG II² 3669 (now in the Louvre) and IG II² 3670. He served as a strategos (στρατηγός, general) during the Herulian invasion of Greece in 267-268 AD (see gallery page 6), and held the offices of Eponymous Archon (Επώνυμος Άρχων, 249-250 AD) and Archon Basileus (Άρχων Βασιλεύς), and was an agonothete (ἀγωνοθέτης, presiding officer) at the Panathenaic Games. He was also the author of three books of history, known from fragments and references in the works of other authors:

1. History; Historical Epitome, summarized by Photios (Bibliotheka, Codex 82: Dexippus, History; Historical Epitome). Thought to have been an epitome of a work by Arrian, The events after Alexander, (Τὰ μετ᾽ Ἀλέξανδρον), about the historical events following the death of Alexander the Great (Photios, Bibliotheka, Codex 92: Arrian, Continuation).

2. Σκυθικά (Scythica), a history of the wars of Rome with the Goths (referred to as "Scythians") in the 3rd century AD.

3. Χρονικὴ ἱστορία (Chronike Historia, Chronicle) in twelve books, thought to deal with the thousand years to the reign of Emperor Claudius Gothicus (270 AD).

A continuation of the Chronicle in fourteen books, written by Eunapius of Sardis (circa 345-420 AD), was summarized by Photios (Bibliotheka, Codex 77: Eunapius, Chronicle).

See, for example:

Gunther Martin and Jana Grusková, "Scythica Vindobonensia" by Dexippus(?): New fragments on Decius' Gothic Wars. In: Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 54 (2014), pages 728-754.

Christopher Mallan and Caillan Davenport, Dexippus and the Gothic invasions: Interpreting the new Vienna fragment (Codex Vindobonensis Hist. gr. 73, ff. 192v–193r). In: Journal of Roman Studies, Volume 105, November 2015, pages 203-226. doi:10.1017/S0075435815000970.

16. Objects in the new Acropolis Museum previously in other museums

Invoice numbers of objects in the Epigraphical Museum, Athens are usually referred to with the prefix of the initial letters ΕΜ (Επιγραφικό Μουσείο) or EM (Epigraphical Museum). A number of artefacts in the museum which were found on or around the Athens Acropolis have since 2007-2009 been moved to the new Acropolis Museum (officially opened in June 2009, usual prefix Ακρ, Akr or Acr), but are still referred to by their original invoice numbers. This also applies to artefacts moved to the new Acropolis Museum from the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, with invoice numbers often referred to prefixed by the initial letters ΕΑΜ (Εθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο, Ethniko Archaiologiko Mouseio), NAMA (National Archaeological Museum, Athens), NAM (National Archaeological Museum) or NMA (National Museum, Athens).

Likewise a number of objects from the national museum are currently in other museums around Greece, such as those at Olympia, Marathon and Andros.

17. The cave of Apollo

An archon (ἄρχων, ruler; plural, ἄρχοντες, archontes) was one of ten ruling magistrates in Athens, elected to serve a term of one year. Each Athenian calendar year was named after the eponymous archon. The other nine archons were the archon basileus (king, responsible for civic religious matters), the polemarch (nominally head of the armed forces), six thesmothetai (court presidents; singular Thesmothetes) and their secretary. Although some of the eponymous archons named in the dedications are known from other documents, most of the other officals mentioned are otherwise unknown.

It has been argued that the wreaths are of myrtle, since archons wore myrtle crowns. However, the laurel (Δάφνη, daphne) was most often associated with Apollo. In Ion, Euripides mentioned several times that the rocky caves below the Acropolis, at the place the Lords call "Long Rocks", were covered by "a dense bush of laurel". Apollo's son Ion arrives at the caves wearing "a garland of laurel with ribbons". Euripides also related that it was a custom of the house of Erechtheus to adorn their children's cribs with platted golden snakes, and that when Kreousa exposed the infant Ion, she had placed a double snake ornament around his neck. This may account for the snakes on the wreaths of the votive plaques.

Daphne (Δάφνη, Laurel) was a Naiad (a female freshwater Nymph) who was turned into a laurel tree (in some versions of the myth by her father, the river god Peneus of Thessaly) when Apollo tried to rape her.

For further discussion on the caves around the Acropolis and other sacred caves in Attica, see:

Kent J. Rigsby, Apollo and the archons. In: Gary Reger, F. X. Ryan and Timothy F. Winters (editors), Studies in Greek epigraphy and history in honor of Stephen V. Tracy, pages 171-176. Ausonius Éditions, Études 26. Diffusion De Boccard, Paris, 2010.

Nadine Pierce, The archaeology of the sacred caves in Attica, Greece. MA thesis, McMaster University, 2006. |

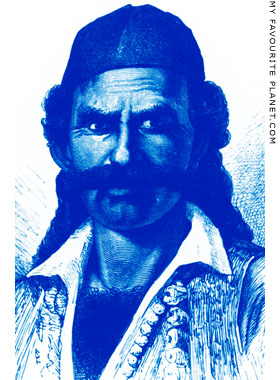

Odysseas Androutsos (1788-1825)

From: Amand Freiherr von Schweiger-

Lerchenfeld (1846-1910), Griechenland

in Wort und Bild, Eine Schilderung des

hellenischen Königreiches. Heinrich

Schmidt und Carl Günther, 1887. |

| |

Detail of a later portrait of

Christopher Wordsworth as

Bishop of Lincoln, published

at the time of his death.

Source: The Illustrated London News,

March 28, 1885, page 326. |

| |

Photos, illustrations, maps and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide comprehensive and accurate information across this website. However, we can take no responsibility for inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services mentioned on these pages. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

| Copyright © 2003-2025 My Favourite Planet | contents | contributors | impressum | sitemap |

| |