|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Dioskouroi |

|

| |

Dioskouroi

Ancient Greek mythology, religion and art

The mythical twin heroes, Kastor (Κάστωρ, beaver; Latin, Castor) and Polydeukes (Πολυδεύκης, much sweet wine; Latin, Polydeuces or Pollux) were known as the Dioskouroi (Greek Διόσκουροι, sons of Zeus; Latin, Dioscuri). [1]

The various versions of the myths concerning the twins are inconsistent and often vague. One twin was said to be the immortal son of the Aetolian princess Leda (Λήδα, daughter of King Thestius) and Zeus, who disguised himself as a swan to have sex with her. The other, conceived the same night, was the mortal son of Leda and her husband King Tyndareos of Sparta (Τυνδάρεως). However, which of the twins was immortal is not clear: it is generally thought that Polydeukes was the immortal son of Zeus, and Kastor the mortal son of Tyndareos.

In some versions of the myths, the coupling of Leda and Zeus as a swan (see below) produced one or two eggs, from which hatched one of the twins and Helen of Troy. [2] At the same time Leda also give birth to the other twin and Clytaemnestra (Κλυταιμνήστρα), conceived by more conventional means with Tyndareos. Helen (Ἑλένη) married Menelaos, king of Sparta, but her abduction by the Trojan prince Paris (see below) led to the Trojan War. Clytaemnestra married Menelaos' brother Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, but murdered him on his return from Troy (see below). In yet another mythological variant, it was Nemesis (Νέμεσις), the goddess of retribution, who was raped by Zeus as a swan and produced an egg from which Helen hatched. The egg was found by or given to Leda who became Helen's nurse (see image below right). [3]

The Dioskouroi were also half-brothers of Timandra, Phoebe, Herakles, and Philonoe.

The twins were closely associated with horses, often depicted as mounted warriors or hunters (such cult images of mythical horsemen were widespread among ancient cultures) and particularly revered by cavalry soldiers.

They also appeared as warriors and hunters in several mythical tales, including the hunting of the Kalydonian Boar (see photos below), the feud between Sparta and Athens following the abduction of Helen by Theseus, and the expedition of Jason and the Argonauts.

There were also tales of cattle theft (see photo below), abduction of women, rivalry, trickery and revenge involving the Dioskouroi and their cousins Lynkeus and Idas (the Apharidae, sons of Aphareus), twin brothers from Messenia [4]. The growing emnity between the two sets of twins ended with Idas ambushing and killing Kastor, and Polydeukes killing Lynkeus.

Other versions of the myths related that both the Dioskouroi were killed in combat by Lynkeus and Idas during a siege of Sparta (Lacedaemon). In the Iliad by Homer, during the siege of Troy Helen asks why her brothers are not among the Greek besiegers (Achaeans) she can see from the walls of the city. Homer tells us that, unknown to her, both were already dead and buried:

"'I see, moreover, many other Achaeans whose names I could tell you, but there are two whom I can nowhere find, Castor, breaker of horses, and Pollux the mighty boxer; they are children of my mother, and own brothers to myself. Either they have not left Lacedaemon, or else, though they have brought their ships, they will not show themselves in battle for the shame and disgrace that I have brought upon them.'

She knew not that both these heroes were already lying under the earth in their own land of Lacedaemon."

Homer, Iliad, Book 3. Translated by Samuel Butler.

After Kastor's death, Polydeukes asked Zeus to allow his twin brother share his immortality so that they could remain together. Zeus transformed them both into the stars today known as the Gemini (Latin for twins) constellation, the heavenly twins. Some ancient authors wrote that they shared immortality in turns. Even Homer, who had consigned them to beneath the earth in The Iliad, explained in The Odyssey that each was alive and then dead on alternate days:

"And I saw Lede, the wife of Tyndareus, who bore to Tyndareus two sons, stout of heart, Castor the tamer of horses, and the boxer Polydeuces. These two the earth, the giver of life, covers, albeit alive, and even in the world below they have honor from Zeus. One day they live in turn, and one day they are dead; and they have won honour like unto that of the gods."

Homer, Odyssey, Book 11, lines 298-304. At Perseus Digital Library.

They are sometimes called the Tyndaridae or Tyndarids (Τυνδαρίδαι, Tyndaridai), a reference to their father / stepfather King Tyndareos of Sparta. The worship of the Dioskouroi appears to have had its origins and centre at Sparta, where they were associated with the Spartan tradition of dual kingship, and there were many sanctuaries dedicated to the twins around the Peloponnese. The cult spread throughout the ancient Greek world, and they were also worshipped by the Etruscans (as Kastur and Pultuce), Romans and Gauls.

Two "Homeric Hymns" [5] are dedicated to the Dioskouroi, in both of which the brothers are referred to as the Tyndaridae, born to Leda below Mount Taygetos (Ταΰγετος), west of Sparta, after Zeus ("Son of Cronos") had slept with her.

"Sing, clear-voiced Muse, of Castor and Polydeuces, the Tyndaridae, who sprang from Olympian Zeus. Beneath the heights of Taygetus stately Leda bare them, when the dark-clouded Son of Cronos had privily bent her to his will.

Hail, children of Tyndareus, riders upon swift horses!"

Homeric Hymn 15, To the Dioscuri at Wikisource.

Hymn 33 also describes the role of the Dioskouroi as the protectors of seafarers, for which they were worshipped at places such as the Northern Aegean island of Thasos (see below).

"Bright-eyed Muses, tell of the Tyndaridae, the Sons of Zeus, glorious children of neat-ankled Leda, Castor the tamer of horses, and blameless Polydeuces. When Leda had lain with the dark-clouded Son of Cronos, she bare them beneath the peak of the great hill Taygetus, children who are deliverers of men on earth and of swift-going ships when stormy gales rage over the ruthless sea. Then the shipmen call upon the sons of great Zeus with vows of white lambs, going to the forepart of the prow; but the strong wind and the waves of the sea lay the ship under water, until suddenly these two are seen darting through the air on tawny wings. Forthwith they allay the blasts of the cruel winds and still the waves upon the surface of the white sea: fair signs are they and deliverance from toil. And when the shipmen see them they are glad and have rest from their pain and labour.

Hail, Tyndaridae, riders upon swift horses! Now I will remember you and another song also."

Homeric Hymn 33, To the Dioscuri at Wikisource.

The city of Tyndaris (Τυνδαρίς; also Tyndarion, Τυνδάριον; today Tindari) in northeastern Sicily was named after the Tyndaridae (Dioskouri) by refugees from the Peloponnese, Zakynthos and Naupaktos, who had been driven from Greece by the Spartans at the end of the Peloponnesian War and were resettled at the location around 396 BC the tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse (ruled 405-367 BC). [6] It was one of the last cities in Sicily to be founded solely by Greeks. They issued coins marked TYNΔΑPΙΤΑΝ (Tyndaritan) with depictions of the Dioskouri.

The twins were also known as Anakes (Ἄνακες, kings; also translated as "protectors", "guardians" and "on high"; Plutarch, Life of Theseus, 33.1), their annual religious festival the Anakeia (Ἀνάκεια), and their temple the Anakeion (Ἀνάκειον).

There was an Anakeion beneath the Sanctuary of Aglauros on the east slope of the Athens Acropolis. Pausanias described a sculpture group and paintings dedicated to them there:

"The sanctuary of the Dioscuri is ancient. They themselves are represented as standing, while their sons are seated on horses. Here Polygnotus has painted the marriage of the daughters of Leucippus, was a part of the gods' history, but Micon those who sailed with Jason to the Colchians, and he has concentrated his attention upon Acastus and his horses."

Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 18, section 1.

Pausanias also mentions that "at Kephale [in Attica] the chief cult is that of the Dioskouroi, for the inhabitants call them the Megaloi Theoi [Great Gods]".

Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 31, section 1.

According to the poet and collector of epigrams Meleager of Gadara (Μελέαγρος ὁ Γαδαρεύς, 1st century BC), the cyclamen (κυκλάμινος) was named after the Dioskouroi:

"... the Muses' cyclamen which takes its name from the twin sons of Zeus." [7]

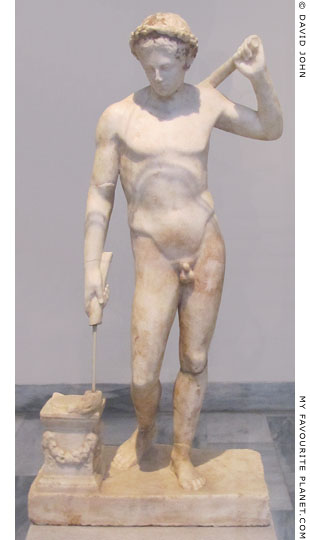

In Greek and Roman art the Dioskouroi are usually depicted as naked apart from a pilos (πῖλος) conical cap ( see Medusa), chlamys (χλαμύς, short cloak) and sometimes boots, each holding a spear and often on or with a horse. They are sometimes shown with a star above each head, particularly on coins (see coins above right and below, and a votive relief below). |

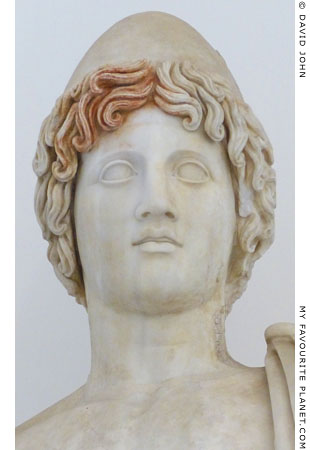

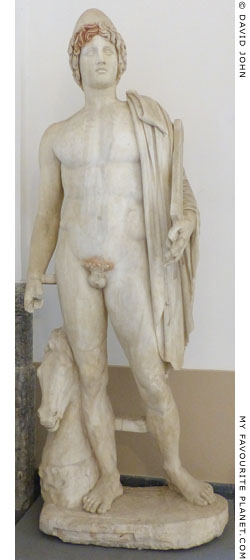

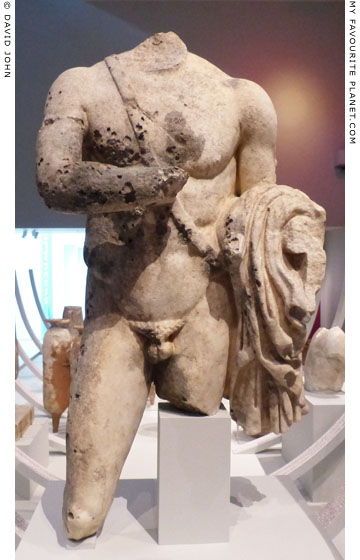

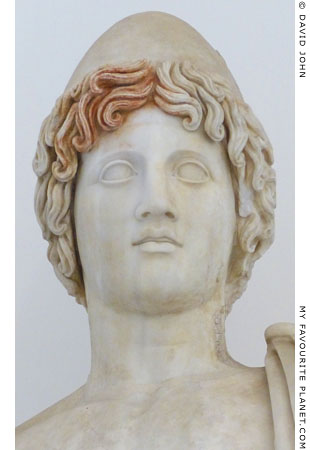

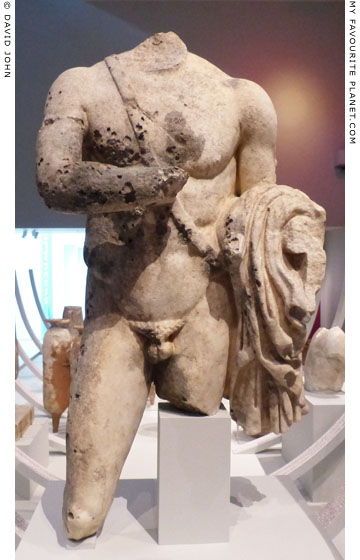

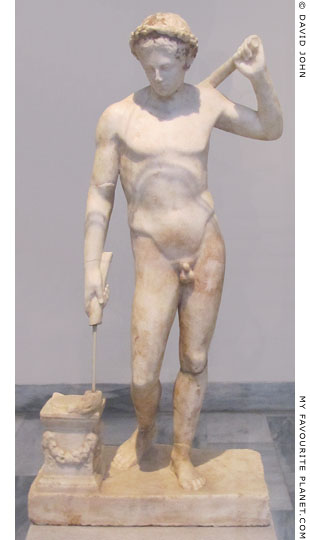

Detail of one of the Dioskouroi statues

in the Naples Archaeological Museum.

See photos below. |

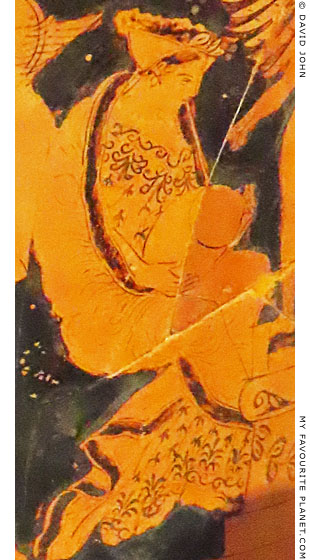

| |

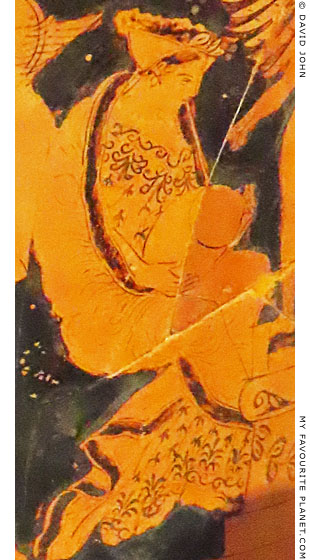

Detail of an Attic red-figure calyx-krater with

a depiction of Leda, seated and holding a

large egg from which Helen of Troy will be

hatched (see the rest of the painting on

the Hermes page).

Around 420-400 BC. Found in Ierissos

(Ιερισσός; ancient Akanthos, Ἄκανθος),

Halkidiki, Macedonia (see History of

Stageira and Olympiada - Part 1).

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. |

| |

The Dioscuri on a bronze coin of

the Roman Republic, 211-170 BC.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme,

National Museum of Rome. |

| |

The Dioscuri on a coin of the Roman

Republic, from Akragas (Agrigento), Sicily.

Agrigento Regional Archaeological Museum. |

| |

The Dioskouri on a coin of the child king

Antiochos VI Dionysus (Αντίοχος Διόνυσος,

circa 148–142/1 BC, aged 7-9) of Syria.

Hellenistic period.

Numismatic Museum, Athens. |

| |

Heads of the Dioskouri, one upright and

the other inverted, on a silver drachm

from Istros (Ίστρος), a Greek colony

founded by Miletus in the 7th century BC

on the Black Sea coast (near modern

Istria, Romania). Circa 400 BC. [8]

Alpha Bank Numsimatic Collection,

Athens, Greece. |

| |

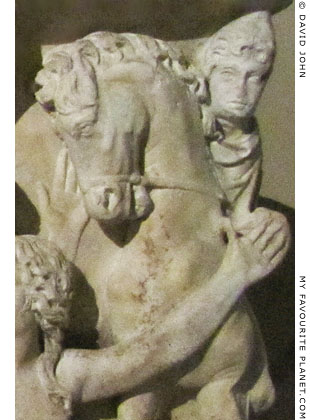

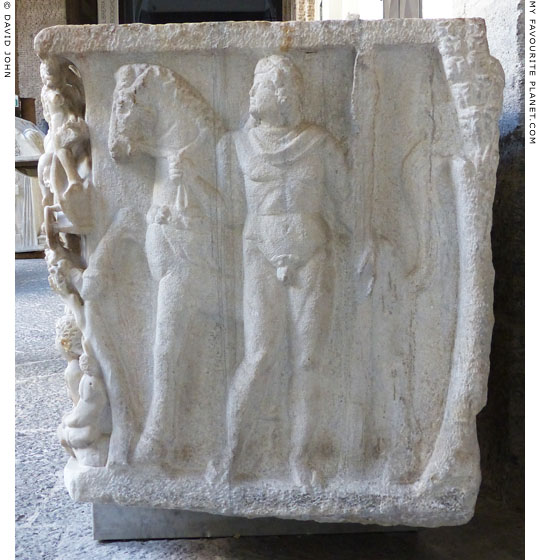

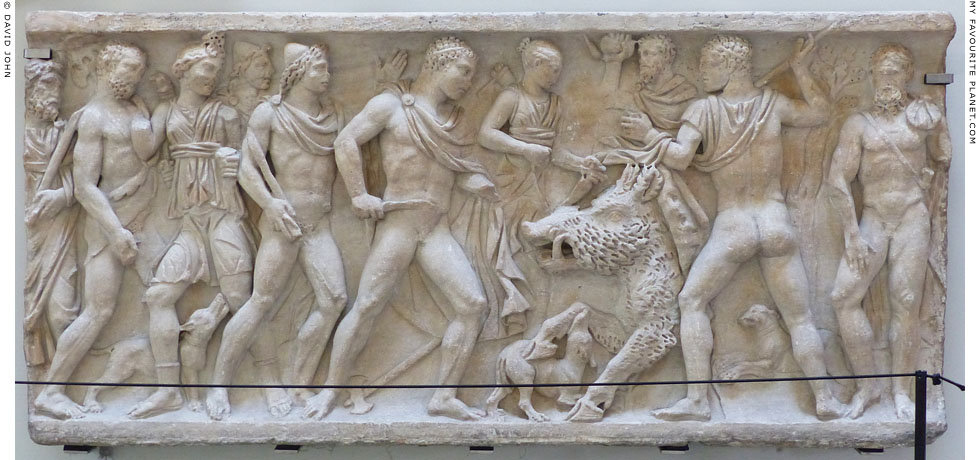

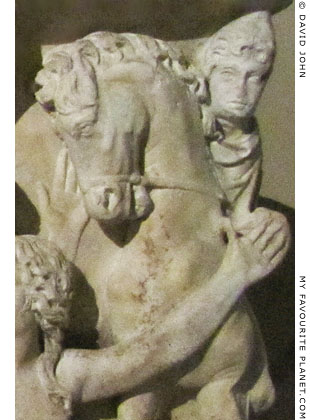

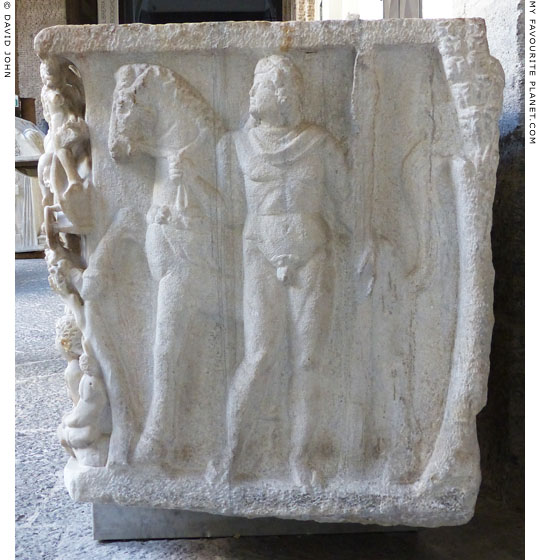

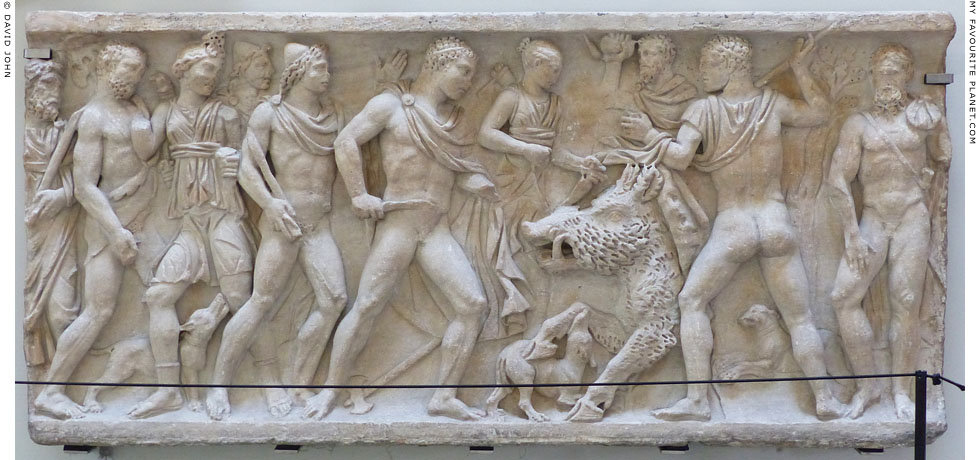

One of the Dioskouri on horseback,

on the corner of a marble relief on

the "Sarcophagus of Meleagros".

From Dyrrachium (Durres, Albania). Roman

period, first half of the 2nd century AD.

The Dioskouri twins sit on horseback on

either side of a relief frieze depicting the

myth of the Kalydonian hero Meleagros.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 2100 T. Cat. Mendel 4. |

| |

| |

Two charioteers, perhaps the Dioskouroi, among horsemen

on an Athenian black-figure spouted krater (large bowl).

Geometric period, 735-720 BC (LGIIa). From Thebes.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1899.2-19.1.

|

The other side of the krater has a painting of a man grasping a woman by the wrist as he turns towards a ship with two rows of oarsmen. Thought to be an early representation of a myth, perhaps Theseus abducting Helen, Paris abducting Helen, the cause of the Trojan war, or Theseus fleeing King Minos of Crete with Ariadne. If the woman is Helen, then the two charioteers may be her brothers Kastor and Polydeukes.

See the other side of the krater in Homer part 2.

See also the Judgement of Paris in Greek, Etruscan and Roman art on the Hermes page. |

|

|

| |

An Archaic high relief depicting a scene from the myth of the Dioskouroi and the Apharidae.

Part of a poros (limestone) metope of the Sikyonian "monopteros", an open

Doric colonnade at the Treasury of the Sikyonians, Delphi. Circa 560 BC.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece. Inv. No. 1322.

|

The five surviving metopes from the Sikyonian monopteros were excavated at Delphi in 1894, in and around the Sikyonian Treasury. [9]

The Kastor and Polydeukes are shown walking to the right, followed by their Theban cousin Idas (Ἴδας, one of the the Apharidae twins), leading cattle as booty from their raid on Arcadia. Around 20 centimetres of the left side of the relief are missing, and it is thought that Idas' twin brother Lynkeus (Λυνκεύς) followed him. Painted inscriptions (two barely visible, on the right) showed the names of the figures.

All three men are shown in profile, at the same size, identical in dress and pose, and walk in step with the left leg in front. Each is naked apart from a chlamys (short cloak), fastened at the right shoulder and open at the side, a thick belt and sandals. Each carries two spears in the left hand, resting on the left shoulder, and another two horizontally in the right hand.

The oxen, shown smaller in scale, walk behind the men in rows of three, with three sets of legs and three heads. The heads are shown one above the other, with those in the rear rows at the top. The heads in the two rear rows are in profile, while those in the front rows are turned to face the viewer frontally. Strangely, the horns and ears of the oxen are shown in front of the men's cloaks. The composition as a whole has surprising depth and a dynamic rhythm, and must have been even more impressive when it was first sculpted and painted.

The brightly painted metopes had an unusual width-to-height ratio of 3:2.

Approximate dimensions: height 58 cm, length 87 cm, depth 16 cm, depth of relief 8 cm. |

|

|

| |

Fragments of an Archaic high relief depicting the prow of the Argo ship. On the left,

Polydeukes (name inscribed), one of the Dioskouroi, disembarks from the ship on horseback.

On the right stand Orpheus (name inscribed) and an unidentified musician, both holding lyres.

Part of a poros metope of the Sikyonian "monopteros", Delphi. Circa 560 BC.

It is thought that the image of the ship occupied three

metopes along the short side of the monopteros.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece. |

| |

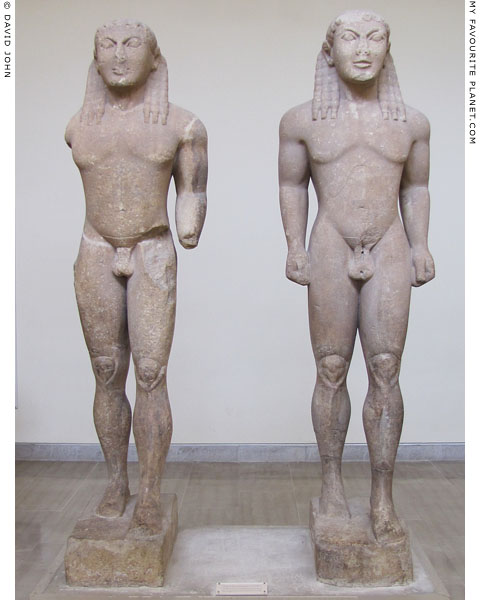

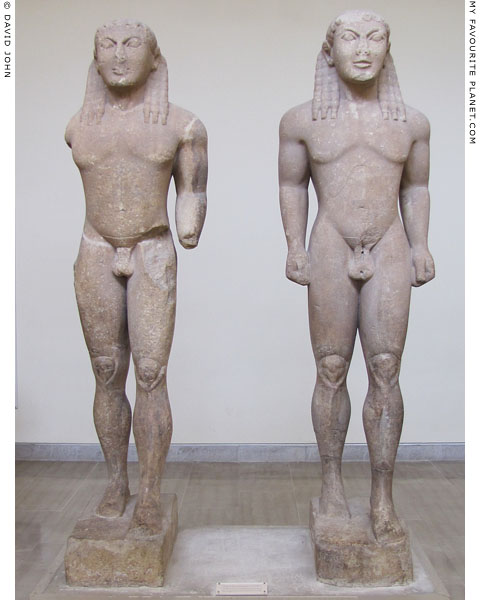

Twin marble kouroi statues in found in Delphi, originally identified as

the legendary or mythical brothers Kleobis (Κλέοβις) and Biton (Βίτων)

of Argos, but now thought by some scholars to depict the Dioskouroi.

Naxian marble. Circa 580 BC. Statue B (left): restored height 218 cm.

Statue A (right): height 216 cm; head height 30 cm;

base height 19 cm, width 38 cm, length 70 cm.

Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece.

Statue B Inv. No. 1524, base 4672. Statue A Inv. No. 467, base 980.

|

Each of the two almost identical over life-size marble kouros statues depicts a muscular young man, standing naked apart from a pair of boots covering his feet and ankles. He steps forward with his left leg in a rigid pose typical of Archaic kouros statues, with each of his arms held at his sides, the fingers of his closed fist resting on the outside of the upper thigh. The head is slightly raised and his gaze is fixed straight ahead. His face is almost triangular, with the top of the head flattish, the forehead low.

Also a typical feature of Archaic statues is the carefully arranged hair, with a row of curls across the top of the forehead, and three thick plaits hanging from behind each ear, resting on the top of the chest. From the rear (photo, right) it is clear that there is a double band around the head at the level of the top of the forehead, and another holding in place the six plaits that hang down to between his shoulders.

It is probable that both figures were made by the same sculptor. As with other statues of the Archaic period, the growing interest in anatomical proportion and detail is evident, but its expression is still a long way from the perfection aspired to during the Classical period. Here muscle bulk is emphasized, while some details such as the edge of the rib cage above the abdomen and the top of the pubic hair are indicated by linear incisions. The modelling of knees on kouroi often seem over-emphasized, great oval lumps sunk between the flesh of upper and lower leg.

The style of the figures, particularly the heads, has been described as "sub-Daedalic", that is with characteristics of the end of the Daedalic style of Archaic Greek sculpture, prevalent around 650-600 BC. Typical are the carving of the hairstyle and facial features, deeply cut brows and eyes, the full lips and the large ears, set far back.

They were discovered during the massive excavations at Delphi, directed by Jean Théophile Homolle (1848-1925), director of the French Archaeological School at Athens (l’École française d’archéologie d’Athènes) 1890-1903.

The first statue, "Statue A" (right in the photo above), was found in May 1893 between the Athenian Treasury (after 490 BC), the Potidean Treasury (circa 500 BC) and the remains of a slightly smaller building of the early 6th century BC, which may have been a sanctuary of the Dioskouroi. Part of its inscribed rectangular base was found in November the same year.

The fragments of the second statue, "Statue B" (left), were discovered in May 1894. Parts of the second base were discovered in 1907, built into a wall of the Roman baths, outside the gate of the sanctuary, at the side of the road to Arachova.

Statue A is almost complete, and the soles of the feet on one of the bases allowed archaeologists to match them. Statue B is more fragmentary and has been restored; the lower legs and part of the base are modern additions. Both statues and bases are badly weathered, but the figures still have a remarkable intensity and presence, despite - or maybe because of - their exaggerated anatomies.

The base of Statue A (Base B) is inscribed with the artist's signature, the first letters of which are no longer legible:

[---]ΜΕΔΕΣ ΕΠΟΙΗΣΕΗ ΑΡΓΕΙΟΣ

([---]medes of Argos made me)

There have been varying readings and interpretations (see images below). The name has been reconstructed by some scholars as Polymedes of Argos (Πολυμεδες Αργειος), while others believe the sculptor was called Agamedes of Argos (Αγαμεδες Αργειος). Neither these are otherwise known as names of sculptors. Another inscribed line and the inscription on the base of Statue B (Base A) are illegible. The perhaps optimistic reading of letters on Base A as part of the name Biton remains a subject of scholarly debate. [10]

The identification of the statues as depictions of the Argive heroes Kleobis and Biton appears to rest on the signature by an Argive sculptor and the questionable reading of Biton's name on Base A, tied to a mention of statues of the brothers by the Greek historian Herodotus.

Kleobis and Biton were two legendary or mythical brothers from Argos whose story was mentioned by Herodotus. The strong young men fell asleep and died after pulling their mother's ox cart 45 stadia (around 8.3 km) to a festival at the temple of Hera in Argos (the Heraion, between Argos and Mycenae) [11], and Herodotus reported that "the Argives made and dedicated at Delphi statues of them as being the best of men". (Histories, Book 1, chapter 31)

It should be noted that Herodotus was relating a story he said was told by the Athenian statesman Solon to King Croesus of Lydia in the first half of the 6th century BC (it is doubted by many modern scholars that these two men ever met); he did not write that he had seen these statues himself or that they still existed in his day. Cicero wrote that the story of Kleobis and Biton was well-known, and it was referred to by a number of later ancient writers, including Polybius, Plutarch, Hyginus, Valerius Maximus, Lucian of Samosata, Pausanias and Diogenes Laertius. However, none of these authors mentioned statues in Delphi. [12]

The theory that the statues were among several dedications to the Dioskouri in Delphi has also yet to be proved, and also rests on conjectural readings of the inscriptions. As in the case of many ancient Greek sculptures, especially Archaic kouroi and korai, without recognizable attributes associated with particular deities and other figures, positive identification remains elusive.

Isotopic ratio analyses of marble samples from monuments in the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi have shown that the statues are made of Naxian marble, from the Melanes or Apollonas quarry on Naxos, and not Parian marble as was previously thought.

See: Olga Palagia and Norman Herz, Investigation of marbles at Delphi. In: J. J. Hermann Jnr., N. Herz and R. Newman (editors), Asmosia 5: Ιnterdisciplinary studies οn ancient stone, pages 240-249. Archetype Publications Ltd., London, 2002. |

The back of the head of statue A.

Other kouros statues

on My Favourite Planet:

The colossal "Isches Kouros" from Samos,

"The Ram-Carrier of Thasos"

and smaller kouroi from Samos:

Samos photo gallery pages 4-5

A bronze kouros statuette in the Daedalic

style in the Delphi Archaeological Museum:

Daidalos page, MFP People

Various kouroi and korai statues:

Ancient Greek Sculptors A-D |

| |

A Roman period copper coin of Argos with

a depiction of Kleobis and Biton pulling their

mother's cart in the form of a chariot.

Source: Friedrich Imhoof-Blumer and Percy

Gardner, A numismatic commentary on

Pausanias, Plate K, XXXIV (text on page 37).

Richard Clay and Sons, London and Bungay,

1887. At the Internet Archve. |

| |

Kleobis und Biton pulling their mother's cart

on a Roman period copper coin of Argos.

Berlin State Museums (SMB).

Source of this drawing and that below:

Julius Friedlaender, Neue Erwerbungen des

K. Münzenkabinets. In: Archäologisches

Zeitung, 27. Jahrgang, pages 97-105,

Tafel 23, 9. Deutsches Archäologisches

Institut. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1869.

At the Internet Archve. |

| |

Kleobis and Biton pulling their mother's

cart on a gem of black glass paste.

100 BC - 100 AD.

Berlin State Museums (SMB).

Inv. No. FG 4372.

From the Stosch collection of gems,

purchased by Friedrich II of Prussia.

This gem was described in: Johann Joachim

Winckelmann, Description des pierres

gravées du feu Baron de Stosch,

Cat. no. IV,17, page 410. André Bonducci,

Florence, 1760. At the Internet Archve. |

| |

| |

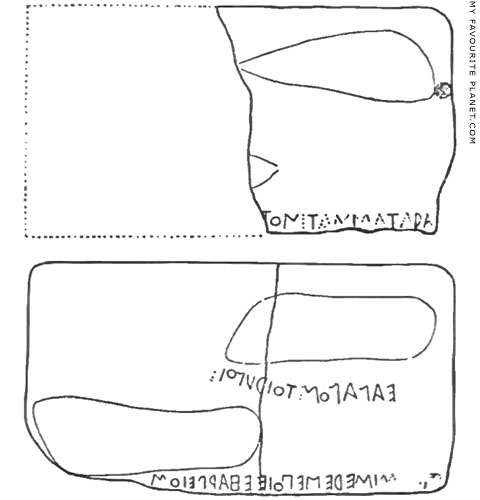

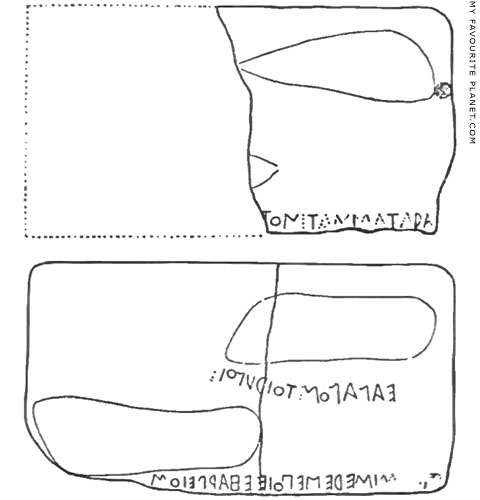

The inscription on the base of Statue A, with the sculptor's signature [---]ΜΕΔΕΣ ΕΠΟΙΗΣΕΗ ΑΡΓΕΙΟΣ

([---]medes of Argos made me), interpreted as either Polymedes of Argos (Πολυμεδες Αργειος)

or Agamedes of Argos (Αγαμεδες Αργειος). The various readings and attempted reconstructions

of the inscriptions on the bases include the ten variants of Syll.³ 5 (Syll.³ 5 - Syll.³ 5[10]).

See inscription Syll.³ 5 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

The other nine variants are on subsequent pages.

Wilhelm Dittenberger (editor) et al, Sylloge inscriptionum graecarum (SIG / Syll.),

3rd edition. 4 volumes. Leipzig, 1915-1924.

Each statue and its base were made from a single stone block.

"The figure, 2.16 metres in height, is of one piece with the base, which is rectangular in shape,

and follows the outside edges of the feet. Such a base, wrought out of the same block as the

statue, was called Σφέλας [sfelas], as is proved by the inscription on the colossal Apollo at Delos."

Frederik Poulson, Delphi, Chapter 6, The Delphian twins, page 90. Translated

by G. C. Richards. Gyldendal, London, 1920. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

Drawing of the bases of the Delphian twins statues. The image of the base

of Statue B (top) has been turned around for easier reading of the inscription.

Source: Frederik Poulson, Delphi, Chapter 6, The Delphian twins, page 95.

Translated by G. C. Richards. Gyldendal, London, 1920. At the Internet Archive.

(Taken from: Anton von Premerstein, Kleobis und Biton. In: Jahreshefte

des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien, Band 13,

pages 41-49, Fig. 28. Alfred Hölder, Vienna, 1910. At the Internet Archive.) |

| |

Jason, the leader of the Argonauts, places his hands over the eyes of the Thracian king Phineas

(Φινέας) to cure his blindness. Kastor and Polydeukes, right, assist. It has been suggested that

the female figure may be the earliest known representation of Queen Kleita (Κλειτα), wife of

Kyzikos, who Apollonias of Rhodes says played a role in the Argonauts' adventure. The names

of the figures are written near their heads.

Fragments of an inscribed black-figure Corinthian column krater, known as "the Argonauts

Krater", made in the workshop of the Cavalcade Painter, around 575-560 BC.

In the lower register is a standing lion. Another fragment shows Zetes and Kalais

(the Boreads, sons of Boreas, the North Wind) chasing the Harpies.

The fragments were discovered in the early 1970s by Stavros Andreadis on his family's

land, at what is now known to be the site of the Sanctuary of Artemis, Sani (ancient Sane),

Kassandra peninsula (ancient Pallene), Halkidiki. He donated them to the museum in 2005.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. MΘ 23656.

(According to the museum catalogue, Inv. No. MΘ 1.)

See: Eurydice Kefalidou, The Argonauts Krater in the Archaeological Museum

of Thessaloniki. In: American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 112, No. 4, October

2008, pages 617-624. The University of Chicago Press. At ajaonline.org. |

| |

Detail of a black-figure column krater (bowl for mixing wine and water)

with two youths flanked by their horses and dogs.

From Vulci. Made in southern Italy, around 540 BC.

Attributed to the Inscriptions Painter (Chalcidian Group).

The figures have not been identified. Perhaps the Dioskouroi or two other heroes.

Pausanias noted that at the Anakeion, the sanctuary the Dioskouroi in Athens,

they "are represented as standing, while their sons are seated on horses."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 18, section 1.

British Museum. GR 1843.11-3.38 (Vase B 15). Canino Collection. |

| |

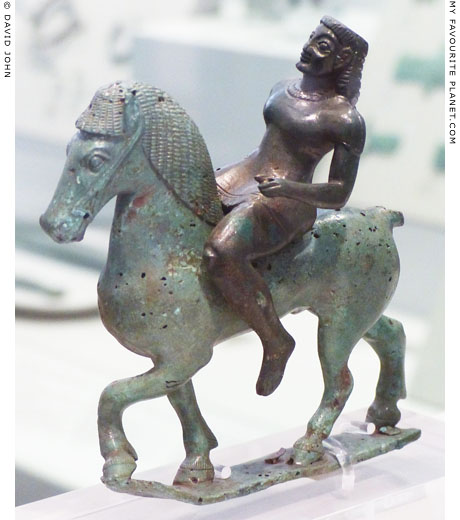

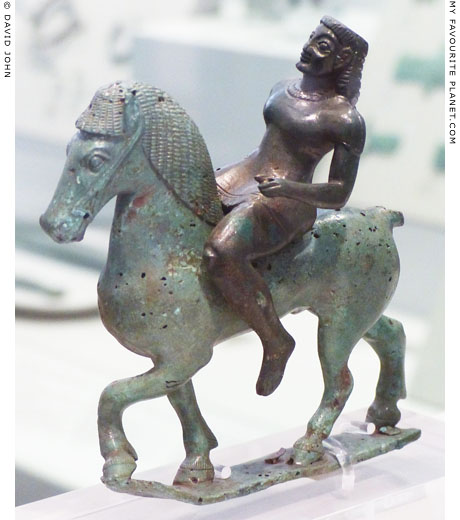

A bronze figurine of a horse and rider, perhaps one of the Dioskouroi.

Around 575-550 BC. From the Sanctuary of Zeus at Dodona, near Ionnina, northwest

Greece. Probably made by Corinthian metalworkers, perhaps living in the area.

The rider was found in 1875 during excavations at Dodona by Konstantinos Karapanos

(see note in Homer part 3). He looks masculine although he appears to have breasts.

He wears a short chiton (tunic), and is thought to have originally worn a petasos (broad-

brimmed hat), and to have held reins in his left hand and a spear in the right. The horse

was found in 1956 during excavations by Professor D. Evangelidis. A similar horse also

found at Dodona and now in the Louvre probably belongs to this rider, while the rider

of the horse above has not been found.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. Nos. καρ. 27 and 16547.

Rider from the Konstantinos Karapanos Collection. |

| |

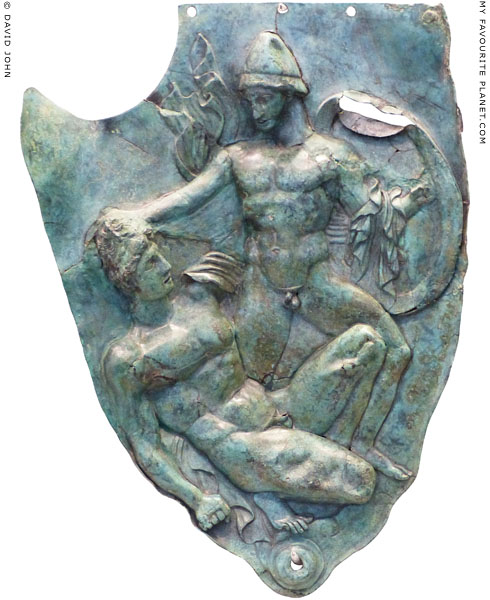

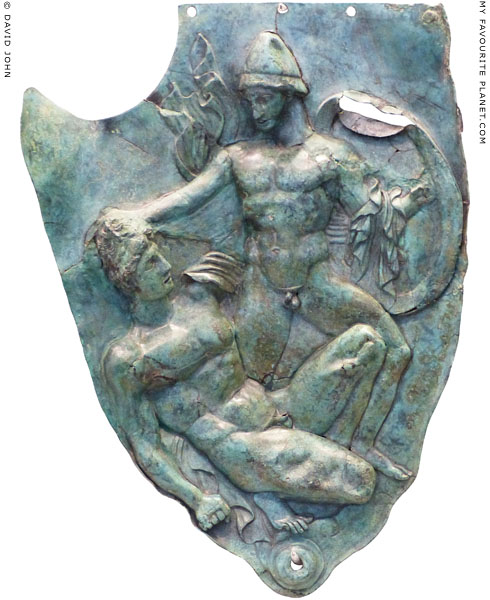

A bronze left cheekpiece of a helmet with a relief of two naked warriors fighting.

The warrior on the right wearing a pilos helmet (see Medusa part 6), a cloak

and carrying a round shield, appears to have defeated his opponent. Perhaps

Kastor fighting Lynkeus or Polydeukes fighting Idas [see note 4].

Late 5th - early 4th century BC. Found in 1875 in the Sanctuary of Zeus

at Dodona, near Ionnina, northwestern Greece, during excavations by

Konstantinos Karapanos (see Homer part 3).

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. καρ. 166.

From the Konstantinos Karapanos Collection. |

| |

Part of a ceramic oil lamp with a disc relief of two naked warriors.

The scene is very similar to that on the bronze cheekpiece above.

In addition, are a shield and a weapon (?) behind the fallen warrior

on the left, as well as what appears to be a Sphinx on a column.

The museum labelling states that they are a hoplomachus and a

Samnite, two popular types of gladiator. But this is unconvincing,

particularly as gladiators did not fight naked, they were equipped

with armour and weapons according to their type. [13]

1st century BC. found in Rhodes. Thought to

have been made in an Italian workshop.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum.

Part of the extended exhibition "Ancient Rhodes - 2400 years"

in the Palace of the Grand Master, Rhodes, 2020-2022. |

| |

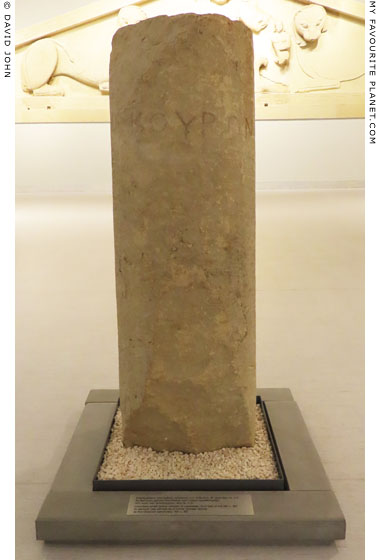

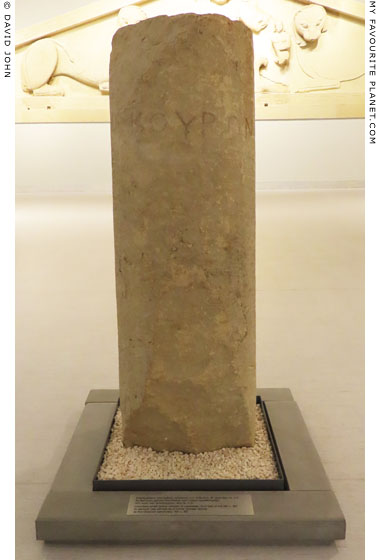

The inscribed limestone grave column of Lexeiatas, second half

of the 5th century BC, reused in the 4th century BC as a horos

(boundary stone) for a Dioskouroi sanctuary. Found in the 19th

century near the Monument of Menekrates in the Garitsa district,

south of the centre of Corfu town (ancient Korkyra). [14]. It

appears that the sanctuary itself has not yet been discovered.

The deceased's name ΛΕΞΕΙΑΤΑΣ (Λεξειάτας, Lexeiatas) is inscribed

retrograde (from right to left, with the letters reversed) and vertically

up the length of the column (see image below). Later ΔΙΟΣΚΟΥΡΩΝ

(Διοσκο̣ύρων, Dioskouron) was inscribed horizontally across the

column, near what is now the top. Height 142 cm, width 33 cm.

Corfu Archaeological Museum. Inscription IG IX 1² 4 883. |

| |

A drawing of the name ΛΕΞΕΙΑΤΑΣ (Λεξειάτας, Lexeiatas)

inscribed retrograde on the horos column in Corfu.

Source: Hermann Roehl, Inscriptiones graecae antiquissimae,

No. 345, page 81. Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1882. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

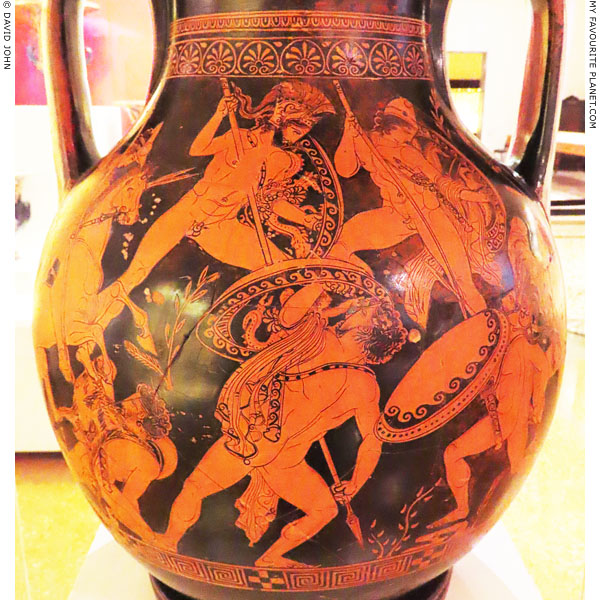

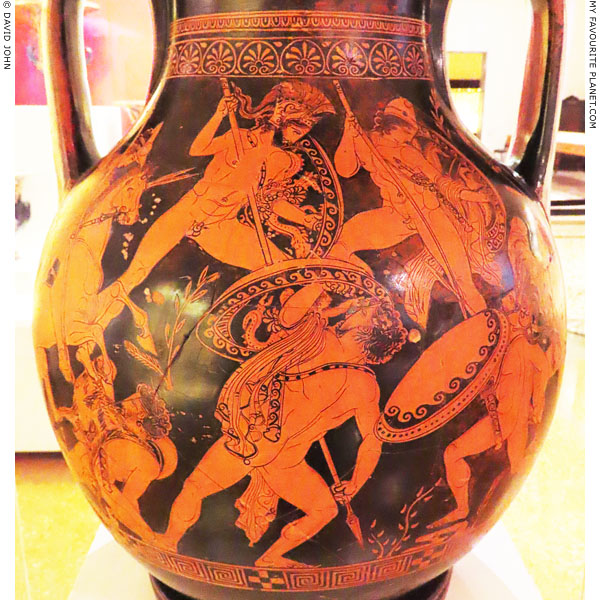

Ares, the Greek god of war, flanked by the Dioskouroi fighting in the Gigantomachy,

the epic battle between the Olympian gods and the Giants. Bearded Ares, wearing

a crested Attic helmet and carrying a spear with his right hand and a round shield

with the left, fights from above. To the right stands one of the Dioskouroi, wearing

a conical pilos helmet, and also armed with a spear and round shield. To the left,

the other heavenly twin rides a rearing horse. He wears a petasos (broad-brimmed

hat) and a chamlys (short cloak), which makes him the only one of the six figures

in the scene who is not nude. He carries a spear in his right hand and two more

in his left hand. The gods fight against three male Giants, similarly armed, who

fight with their back to the viewer.

On Side B: four youths, conversing, three standing, one seated. All a nude apart

from chlamydes (short cloaks) over their shoulders. Each holds two spears,

and has a petasos hanging behind his head. Plants suggest a rural setting.

An Attic red-figure pelike in the manner of the Pronomos Painter,

around 400 BC. From Tanagra, Boeotia, central Greece.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Vase collection. Inv. No. 1333. |

| |

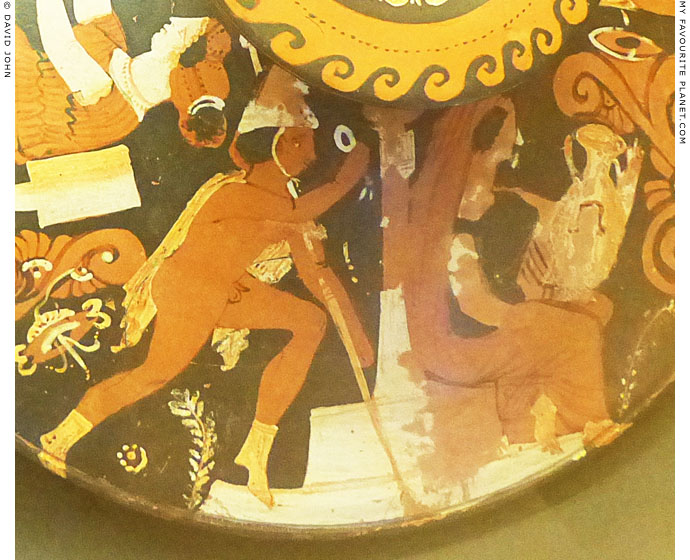

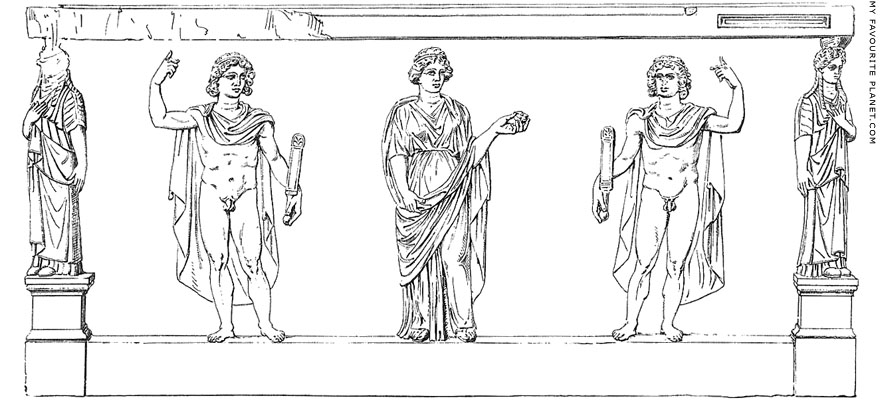

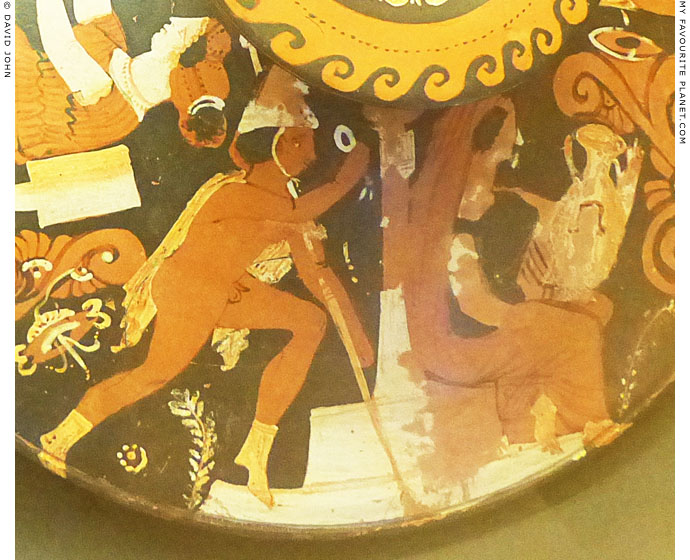

The lid of a Paestan red-figure lekanis [15] depicting a scene from the myth of

Orestes and Elektra: the Dioskouroi appear at the tomb of Agamemnon.

Attributed to the Floreale Painter, circa 330 BC. Excavated in 1954

at Tomb 5 in the necropolis at Laghetto, just northwest of Paestum.

National Archaeological Museum of Paestum, Campania, Italy.

|

In Greek mythology and literature, Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, was murdered on his return from the Trojan War by his wife Clytaemnestra and her lover Aigisthos. Orestes and Elektra, the children of Agamemnon and Clytaemnestra, avenged their father by killing their mother. The cycle of revenge and murder was mentioned in the poetry of Homer and Pindar and was the subject of plays by the Athenian tragedians Aeschylus, Euripides and Sophocles. At the end of Euripides' Electra (Ἠλέκτρα, written around 410-413 BC), the deified Dioskouroi appear and tell Orestes and Elektra that their mother's punishment was just, but they must nevertheless atone for their matricide and purge their souls.

At the front of this lekanis lid, as it appears in the photo above, Elektra sits mourning her father on his tomb. She is veiled and holds what appears to be a vase, perhaps Agamemnon's funerary urn. What appear to be two white teardrops can be seen in front of her face, but the paint is too worn to be certain. The Dioskouroi twins approach her from either side (see detail below; unfortunately the lekanis is displayed at the corner of a glass case, and its position and reflections made it it impossible to take a photo of both twins). Each is naked apart from a pilos (πῖλος) conical cap (see Medusa), chlamys (short cloak) and boots, and each holds a spear and another object which is offered to Elektra. It is uncertain what the twin on the left is holding, but his brother to the right of Elektra offers a golden wreath.

On other vases depicting this subject, two similar figures, dressed in the same way, have been identified as Orestes and Pylades, his cousin who, in some versions of the story, assisted in the killing of Clytaemnestra and Aigisthos.

See also:

Orestes killing Clytaemnestra on a bronze Etruscan mirror, in Homer part 3;

a "Melian" relief of Orestes and Elektra at the tomb of Agamemnon, in Homer part 3. |

|

|

| |

One of the Dioskouroi with Elektra on the lid of the Lekanis in Paestum. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

| |

| |

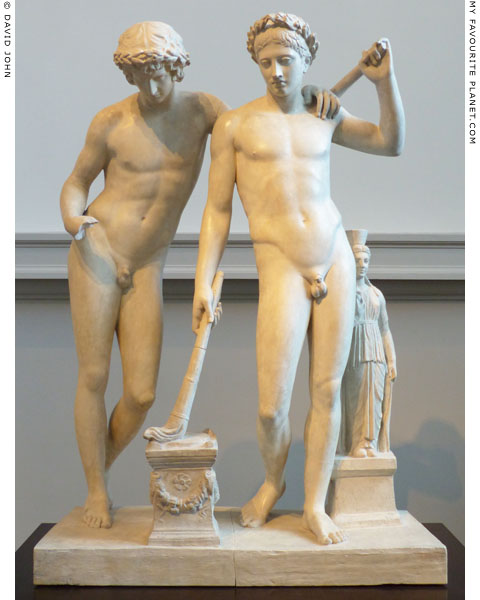

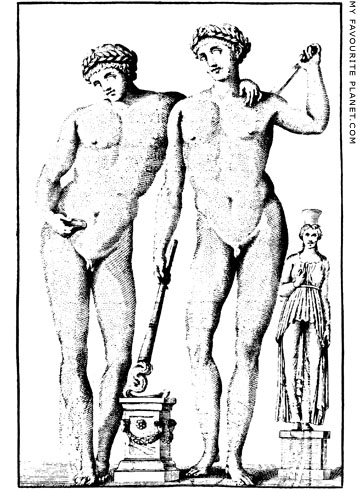

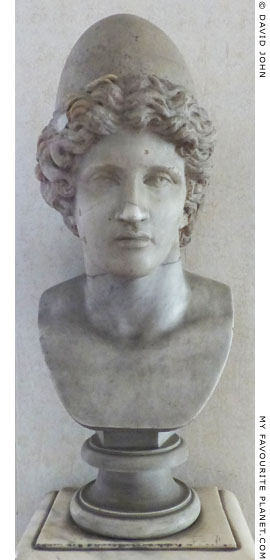

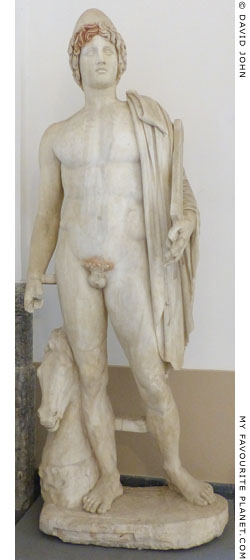

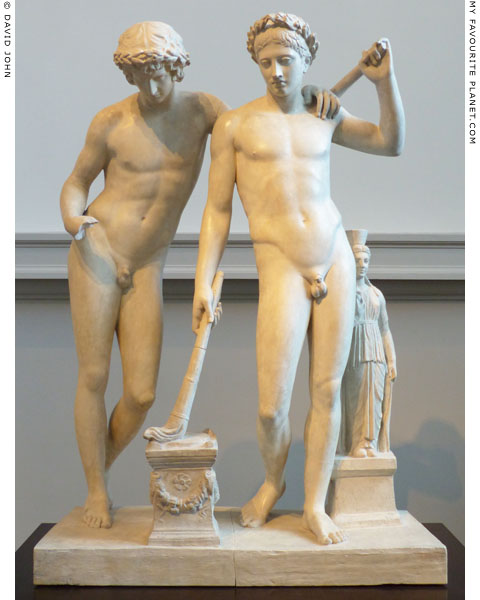

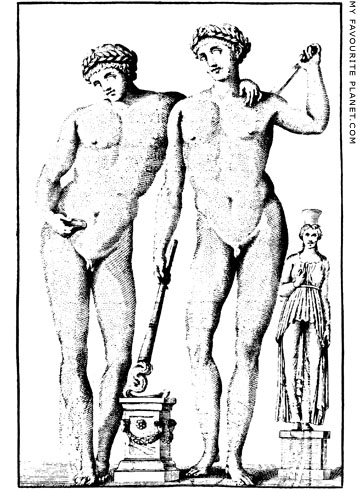

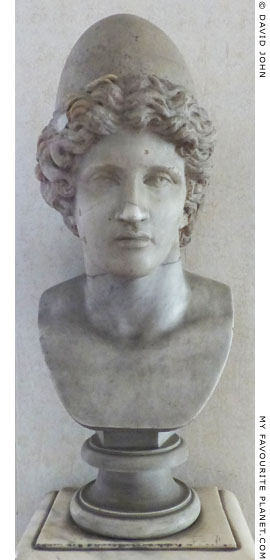

Colossal marble statues of Castor and Pollux, the Dioscuri.

2nd century AD, based on Greek models of the 5th century BC, particularly the

Doryphoros (spear carrier) of Polykleitos. Found at Baiae, in the Bay of Naples,

in the area of the baths, near the "Tempio di Venere" (Temple of Venus).

The twins are usually represented nude; each wears and pilos (πῖλος) conical cap

and a chlamys riding cloak. They are also nearly always shown with horses, here

reduced to a head and neck standing against the right leg of each figure and thus

doubling as a support for it. Both figures hold swords in their left hands.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. Nos. 131209 and 230872. |

| |

|

|

|

The statues of Castor and Pollux in the Naples Archaeological Museum.

There appears to be no indication of which twin is which. Traces of

dark red colour can be seen on the hair of the statue on the left. |

|

| |

|

|

|

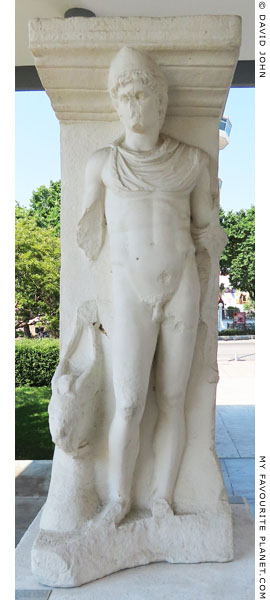

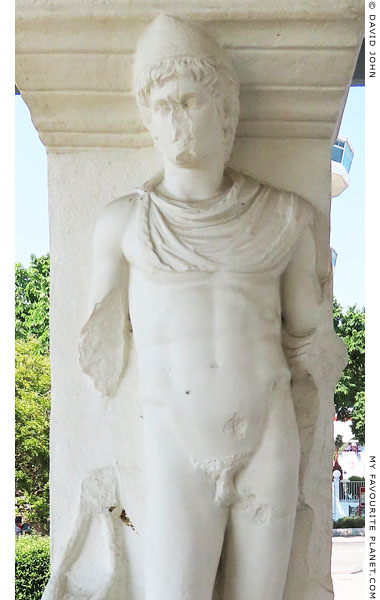

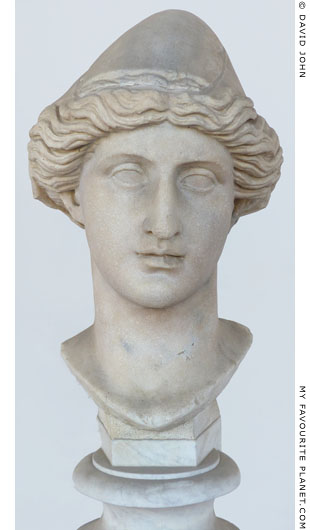

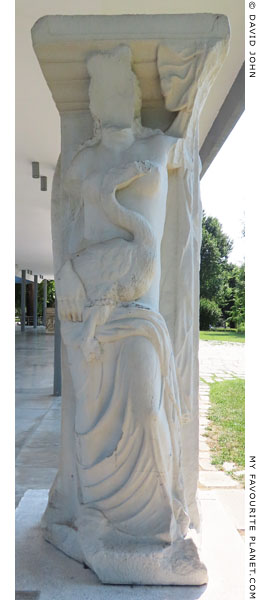

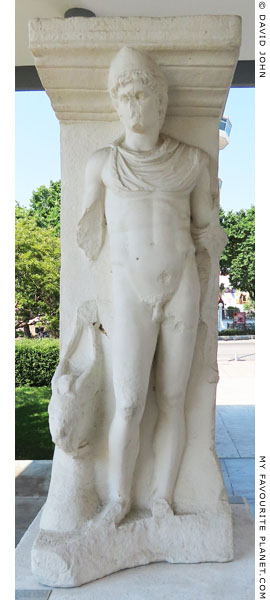

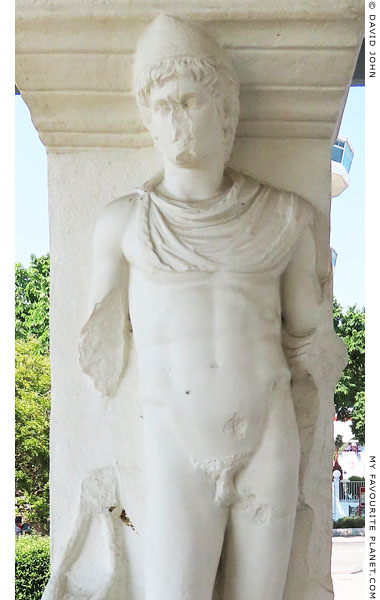

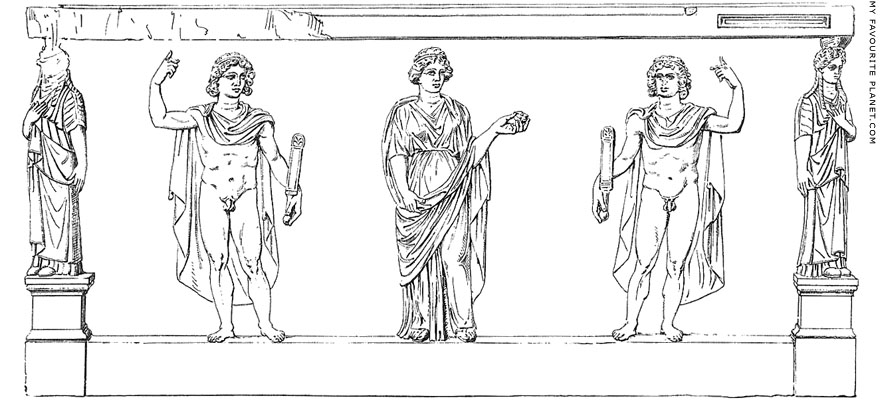

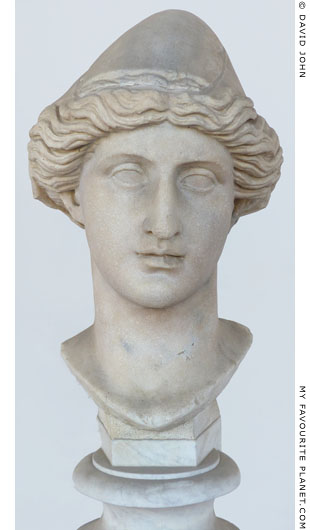

A replica of a marble high relief of one of the Dioskouroi on a pilaster from "Las Incantadas"

(the Enchanted Ones, see below) in Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece. The four pilasters

of the group have reliefs of Greek mythological figures on each side. On the other side

of this pilaster is a relief of Ariadne (see Dionysus).

Height 218 cm. The originals, of the late 2nd or early

3rd century AD, are now in the Louvre, Paris.

Like the Dioskouroi statues in Naples (above) and on the Roman Capitol (below), the

figure stands naked apart from a pilos cap and a cloak, in this case over his chest,

shoulders and part of his left arm. With his missing right hand he probabably held the

reins which rise from the head of the horse, which is shown only as a bust at his side.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

Original, Louvre, Paris. Inv. No. Ma 1392. |

|

| |

"Las Incantadas" standing in its original position in Thessaloniki in the mid 18th century.

A coloured print from a drawing by James Stuart, 1754. [16]

|

"Las Incantadas" (the Enchanted Ones) was the name given by Sephardic Jews of Thessaloniki during the period of Ottoman occupation to the 13 metre high remains of a two-storey marble colonnade that stood between Egnatia Street and the ancient Agora (today a park in the area where the statue of Eleftherios Venizelos now stands). It was known to the Greeks as "the Portico of the Idols" (η Στοά των Ειδώλων, i Stoa ton Eidolon), "The Enchantment" (Γοητειᾒα, Goeteia) or "the Magicians" (Οι Μαγεμένες, oi Magemenes), and to the Turks as "Suret-maleh" (angel figures).

A row of five columns with Corinthian capitals supported an inscribed epistyle on which stood four pilasters, each with a high relief of a Greek mythological figure on two sides. It is thought that originally the colonnade may have had more columns and at least one more pilaster, and that it may have been part of a baths complex.

During the Ottoman period the ruin of the colonnade became part of the courtyard of a Jewish merchant's house in the Rogos district, the city's only Jewish quarter above Egnatia Street. They were admired by a number of early European travellers who visited the city, notably James Stuart and Nicholas Revett [see note 16]. In 1864 the French palaeographer Emmanuel Miller, with the permission of the Ottoman authorities, removed the pilasters amid angry protests by local people, and sent them to the Louvre in Paris.

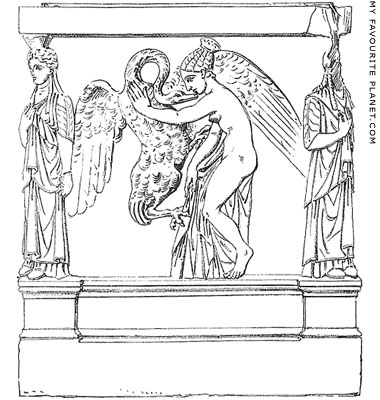

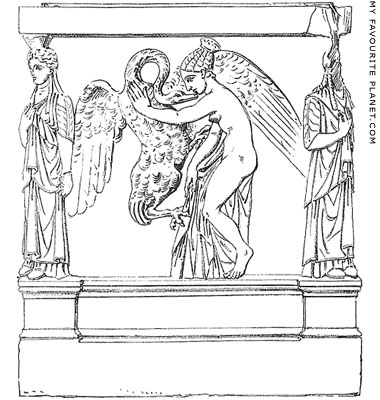

The order of the reliefs on the surviving pilasters, according to drawings by Stuart and Revett: along the north side of the colonnade (east-west), Nike, Aura, Dioskouros, Ganymede and the eagle (Zeus); along the south side (east-west) Maenad, Dionysus, Ariadne, Leda and the swan (Zeus).

The north side of each pilaster is usually referred to as Side A, and the south side as Side B. The pairs of reliefs on each pilaster, from east to west, and their respective Louvre inventory numbers:

Pilaster 1, Inv. No. Ma 1391

north side (A) Nike

south side (B) Maenad

Pilaster 2, Inv. No. Ma 1393

north side (A) Aura

south side (B) Dionysus

Pilaster 3, Inv. No. Ma 1392

north side (A) Dioskouros

south side (B) Ariadne

Pilaster 4, Inv. No. Ma 1394

north side (A) Ganymede and the eagle (Zeus)

south side (B) Leda and the swan (see photo below)

In 1997, during rescue excavations by archaeologists in Rogote Street (Οδός Ρογκότη) in the city centre, a fragment of another of the pilasters was discovered, with part of the head and a wing of a Nike relief (see photo, right). This is thought to be the only surviving part of the stoa now in Greece. Although the Roman period colonnade has generally been dated to the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD, according to the labelling of the Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum, the fragment was made around 225 AD.

As with the "Elgin Marbles", recent campaigns for the return of the pilasters to Greece have so far been unsuccessful, but did result in replicas made of Thassian marble being sent to Thessaloniki in September 2015. The copies cost 150,000 Euro, paid for by HELEXPO Thessaloniki International Fair (ΔΕΘ, TIF). Since September 2017 they have been exhibited in the open, roofed portico of the archaeological museum (see photo below). There are plans to move them to the small museum in the ancient Agora, which would be a good idea, as they are currently exposed to the weather and environmental pollution.

Update 2022: It appears that plans to move the pilaster replicas to the ancient Agora have been abandoned, and they are to remain in the porch of the Archaeological Museum for the forseeable future. |

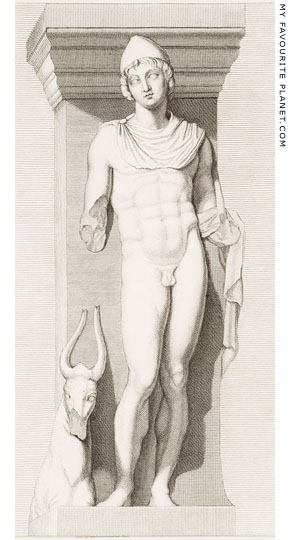

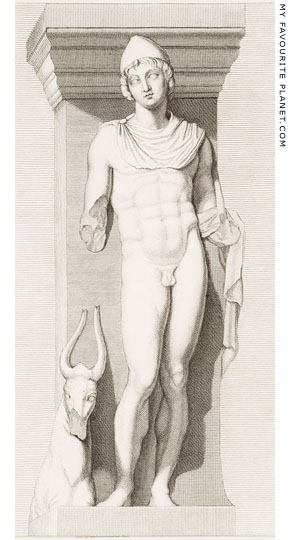

A drawing of the Dioskouros figure from

"Las Incantadas" by James Stuart and

Nicholas Revett, 1753-1754. |

| |

The fragment of the top of a pilaster

from Las Incantadas with part of a

relief of Nike. Found in 1997.

According to the museum labelling,

around 225 AD.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

The four copies of the pilasters from "Las Incantadas", as displayed in

the portico of Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. The view is hindered

by the columns. Left to right: Ganymede, Dioskouros, Aura, Nike |

| |

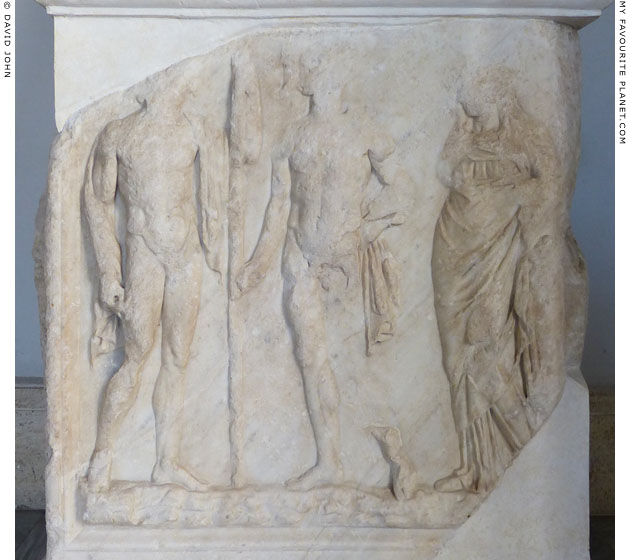

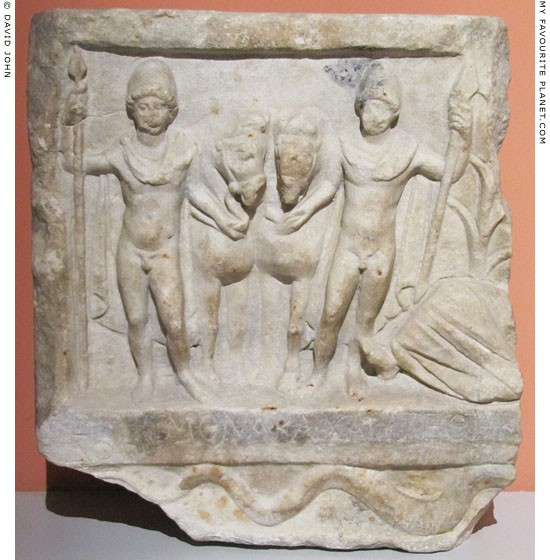

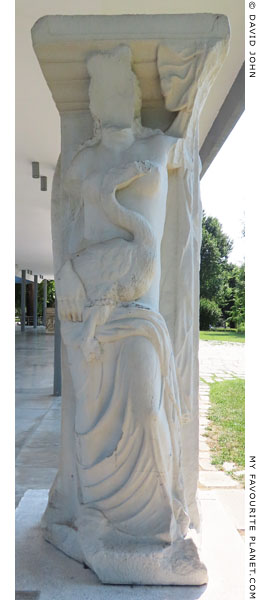

Fragment of an inscribed votive relief of Kastor and Polydeukes, the Dioskouroi,

and part of the reclining river god Strymon (Στρυμών), the personification of the

River Strymon, which flows though Amphipolis [17].

From Amphipolis, Macedonia, Greece. 2nd century AD. Roman Imperial period.

Amphipolis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 673.

|

The mirrored figures of the Dioskouroi stand either side of their horses, facing frontally. Each is naked apart from a pilos (πῖλος) conical cap, chlamys (χλαμύς, short cloak), and holds a spear in the outer hand and the reins of his horse in the other. Only the front parts of the horses are shown. A tree or large plant and a foot and the lower part of the himation (cloak) of the reclining river god Strymon can be seen on the right edge of the broken stele. Below the inscription on the bottom of the frame of the relief is a serpent, a common feature of hero reliefs (see Pergamon gallery 2, page 10). The snake appears to be drinking or feeding from a spoon or leaf shaped object.

The remains of the inscription below the relief:

[C]ΤΡΥΜΟΝΑ ΚΑΙ ΧΑΡΙΤΕCΘΗΚ - - - -

ΔΟ

The quality of the workmanship is poor, and, as ever, it is tempting to believe that it is a copy, a faint echo, of a much finer work of an earlier age. No such original masterpiece has yet been discovered, but the iconography appears in several surviving ancient works, mostly from the Roman period, as can be seen in other photos on this page. |

|

| |

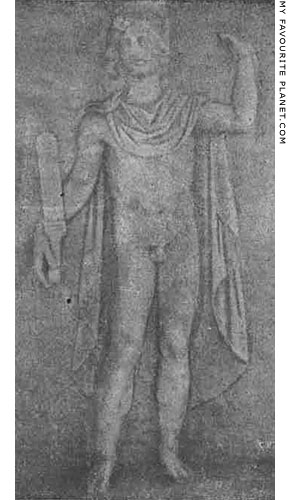

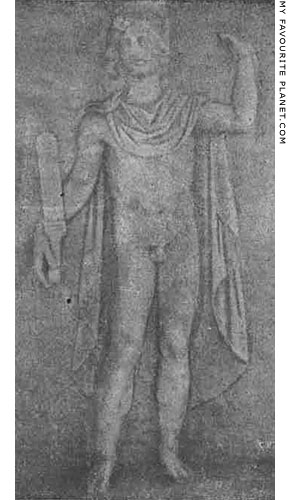

A Roman sandstone votive relief depicting one of the Dioscuri.

Roman. 2nd - 3rd century AD. Known since 1611 when it was recorded

among several ancient stone monuments in the Retscherhof, Speyer

(ancient Noviomagus / Civitas Nemetum, Germania Superior), Rheinland-Pfalz,

Germany. Height 42 cm, width 44 cm, present depth 17 cm.

Historisches Museum der Pfalz, Speyer, Germany.

The male figure, naked except from a cloak, stands in front of horse which faces left

and has one front leg raised. With his left hand he holds the horse's reins, and in

his left hand he holds an upright spear, the bottom of which rests on the ground.

The stone slab, the back of which is broken off, is thought to have been the base

for a column monument dedicated to Jupiter. It may have been one of a pair, each

showing one of the Dioscuri. On the left side is part of an inscription:

[---] Reg(inae?) / [---]orat- / [---]aug- / [---]ani- / [---]a

Inscription CIL 13, 11691.

See other Roman reliefs from Rheinland-Pfalz on the Hephaistos and Hermes pages. |

| |

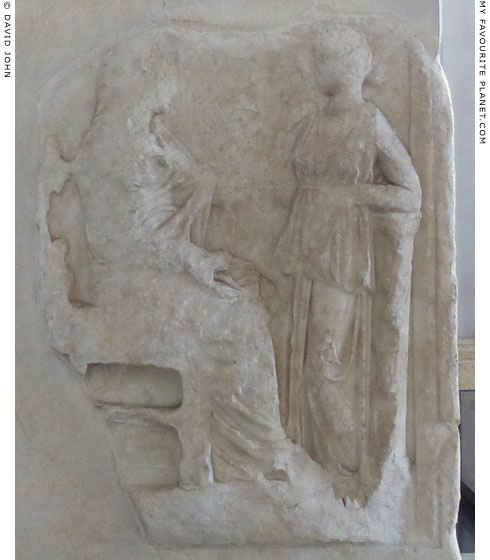

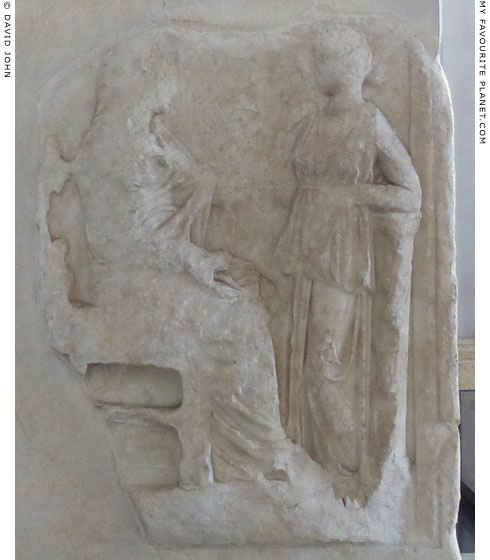

A relief of a youth with a horse, perhaps Castor

on the right side of a marble sarcophagus.

3rd century AD.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 6705.

|

The main relief on the highly polished front panel of the sarcophagus contains a complex scene representing the creation and destruction of man, which includes Prometheus among a number of gods and other mythological characters. The reliefs on the sides of the sarcophagus are more roughly carved. On the left side Atropos is shown determining the hour of death with a sun dial.

Since the theme of the reliefs is mortality, it has been suggested that the youth with a horse is Castor as the mortal twin of the Dioskouroi. He is shown bare-headed and naked, apart from a cloak over his shoulders. He stands frontally, with his head turned to the left. With his left hand he holds a spear and with his right hand he holds the reins of the horse that stands behind him, facing left with its right fore-hoof raised. |

|

| |

A bronze lamina (plaque) inscribed with a dedication in archaic Latin to the Dioscuri.

Castorei Podlouqueique qurois

To Castor and Pollux, youths

Late 6th century BC. Found at the Sanctuary of the Thirteen Altars,

Lavinium (today Pratica di Mare), an ancient port of Latium, around

30 km south of Rome and 22 km southeast of Ostia.

Height 5.0 - 5.3 cm, width 29.1 cm, thickness 0.10 - 0.15 cm.

Baths of Diocletian, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 135931.

Inscription CIL I(2): 2.4, 2883.

|

The lamina, known as "La Tabella Lanuvina", is broken in two pieces, which were discovered separately in August 1958, during excavations directed by Ferdinando Castagnoli (1917-1988) of the University of Rome. The five holes in the thin plaque, one at each corner and another in the centre, were for attaching it to another object, perhaps one of the thirteen altars.

The inscription, written in reverse letters and from right to left, is the earliest evidence of the cult of the Dioscuri in Latium. In this inscription their names and title appear to be direct transliterations into Latin from the Greek: Castorei (Κάστωρης, Kastores), Podlouquei (Πολυδεύκης, Polydeukes) and qurois (κούροις, kourois, youths), which has also been translated as "young knights" and "sons (of Zeus)". The twins were often referred to in Latin as the Castorei (Castores).

Ferdinando Castagnoli, Dedica arcaica lavinate a Castore e Polluce, in Studi e materiali di storia delle religioni, Volume 30, Fasc. 1, pages 109-117. Cesare Marzioli Editori, Rome, 1959. At Università degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza". |

|

| |

The three remaining Corinthian columns, part of the entablature and

the raised substructure of the Temple of the Dioscuri (Castores) on the

south side of the Sacra Via (right of the temple), in the Roman Forum.

|

Worship of Castor and Pollux, as the patrons of the knights, is thought to have been adopted by the Roman aristocratic party in the early 5th century BC. According to legend, two mysterious horsemen led the Romans to victory over the Etruscan Tarquins and Latins at the Battle of Lake Regillus around 499 BC. Shortly after, the pair, identified as the Dioscuri, appeared watering their horses at the Pool of Juturna, near the Temple of Vesta in the Forum, before announcing the Roman victory and then disappearing.

"And when the Romans conquered the Tarquins, who had taken the field against them with the Latins, two tall and beautiful men were seen at Rome a little while after, who brought direct tidings from the army. These were conjectured to be the Dioscuri.

The first man who met them in front of the spring in the forum, where they were cooling their horses, which were reeking with sweat, was amazed at their report of the victory. Then, we are told, they touched his beard with their hands, quietly smiling the while, and the hair of it was changed at once from black to red, a circumstance which gave credence to their story, and fixed upon the man the surname of Ahenobarbus, that is to say, Bronze-beard [Χαλκοπώγων, Chalcopogon]."

Plutarch, Aemilius Paulus, chapter 25, sections 1-2. At Perseus Digital Library.

The temple (also referred to as the Aedes Castoris) was probably built by the general and dictator Aulus Postumius Albus circa 484 BC [18]. The Roman knights held an annual parade in front of the temple on the 15th July. It was restored after 200 BC, and reconstructed in 117 BC by the consul Lucius Caecilius Metellus Dalmaticus following his victory over the Dalmatians. After being destroyed by fire in 14 or 9 BC, it was rebuilt during the reign of Emperor Augustus and inaugurated in 6 AD by Tiberius (later Augustus' successor). Although it was later restored several times, the existing remains are thought to be mostly from the Augustan period, apart from the podium which is that constructed by Metellus.

The peripteral temple, built on a podium approximately 32 x 49.5 metres and 7 metres tall, had 8 Corinthian columns, 12.5 metres tall, at either end, and eleven on each side. Like many of the ancient buildings of the Forum, it was built on a high substructure because of the marshy, uneven ground of the valley. The senate often met here and the building served as the office of the weights and measures inspectors. It had a tribune for orators and booths for bankers (or money changers).

Directly in front of the temple, the shrine of Juturna, the nymph of healing waters, was in the form of the Pool of Juturna (Lacus Juturnae) fed by a spring. Following the victory of the Roman consul and general Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus (circa 229-160 BC) over the Macedonian king Perseus at the First Battle of Pydna in 168 BC, the Dioscuri are said to have appeared again in the Forum. Aemilius Paullus built a fountain at the shrine, with a monumental basin in which were statues of the horses of the Dioscuri. The temple (or chapel) of Juturna was rebuilt during the reign of Trajan (98-117 AD). |

|

Roman denarius showing Castor and Pollux

with their horses drinking from a fountain.

Issued by C. Publicius Malleolus,

A. Postumius Albinus and

L. (Caecilius) Metellus, circa 96 BC.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme,

National Museum of Rome. |

|

| |

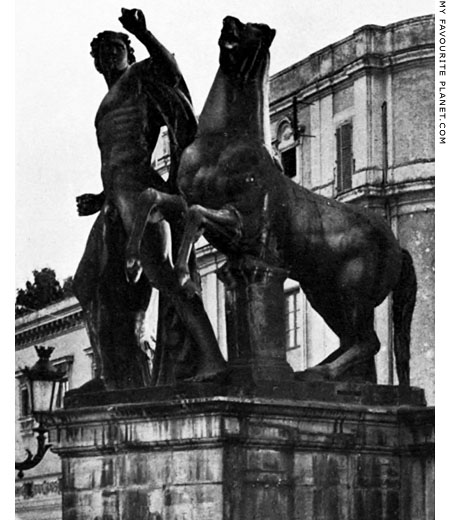

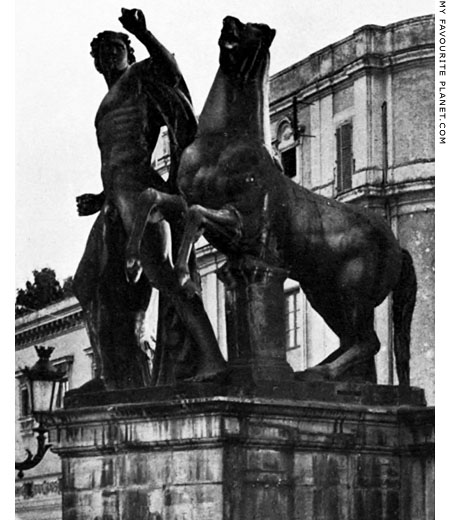

Colossal marble statues of Castor and Pollux standing with horses

on the balustrade flanking the top of the Cordonata, the stairway up

to the Piazza del Campidoglio, the square of the Capitoline Hill, Rome. |

| |

Colossal marble statues of Castor and Pollux with horses on the Piazza del Campidoglio, Capitoline Hill, Rome.

|

In the background is the Palazzo Senatorio, the 12th century senate house of the commune of Rome, now the offices of the city's mayor. It was restored by Michelangelo in 1546 and several times thereafter. The bell tower with the clock was added in 1582. The equestrian statue of Emperor Marcus Aurelius in the centre of the piazza has been replaced by a copy. The original is now in the Palazzo dei Conservatori of the Capitoline Museums, on the right of the piazza.

The balustrade, designed by Michelangelo, is decorated with several sculptures, previously intended to include two other colossal statues of Castor and Pollux which now stand on the Palazzo del Quirinale (see below).

The present statues were discovered either in the Ghetto or in the ruins of the Theatre of Pompey around 1561, during the time of Pope Pius IV (1559-1565). It is thought that they may have originally stood at the temple of the Dioscuri in the area of the Circus Flaminius (aedes Castori Polluci in Circo Flaminio), about which little is known. [19]

The account of the discovery of the statues by the contemporary Roman sculptor and antiquarian Flaminio Vacca (1538-1605):

"At the side of the Tiber, where at present they are making the Synagnogue of the Jews; in the time of Pius IV, there were found two giants holding two horses of statuary marble, which were transported to the Campidoglio, and collocated at the head of the stairs at the end of the Piazza, where at present they are to be found. And it was the opinion of some that said statues, were of Pompey, and of others, of Castor and Pollux from certain pumpkins like half eggs on their heads."

Flaminius Vacca, Memorie di varie antichità trovate in diversi luoghi della città di Roma (Memories of various antiquities discovered in diverse locations in the city of Rome), No. 59. Rome, 1594. Quoted in: Shakspere Wood, The Capitoline Museum of Sculpture, a catalogue, page 9. Printing office of the Propaganda Fide, Rome, 1872.

A more recent account by Wolfgang Helbig (1839-1915):

"The two Colossal Statues of the Dioscuri were discovered under Pius IV, apparently during the construction of the synagogue in the Ghetto *; and for a time lay, unrestored, behind the Balustrade. Some years later they were restored by the sculptor Valsoldo, and in 1583 they were erected on the Balustrade, at the head of La Cordonnata, or grand staircase ascending from the Piazza Aracoeli to the Capitol Square.

The figures are recognizable as the Dioscuri mainly by the pileus on their heads and by the horses which stand beside them. The horses are represented on a small scale in conformity with the principle of ancient art which emphasized the principal figures even at the cost of truth to nature. Each of the youths held his horse with one hand by the bridle, which was presumably added in bronze, while with his other he grasped a wooden or bronze spear. The execution is purely decorative in style and quite insignificant. In antiquity the two statues were probably placed as the ideal watchers of some monumental entrance."

* "Rom. Mittheilungen, VI, p. 33, According to the inscription on the back of the base of the figure to the right (as we look from the Piazza Aracoeli), both statues were found among the ruins of the Theatre of Pompey. The above statement, however, given on the authority of Flaminio Vacca (Berichte der philolog.-histor. Klasse der Sachs. Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften, 1881, p. 70, No. 52), seems more worthy of credence, as Vacca writes as an eye-witness of the discovery."

Wolfgang Helbig, Guide to the public collections of classical antiquities in Rome, Volume I, pages 287-288. Karl Baedeker, Leipzig, 1895.

The statue fragments were added to others found previously. Finally, Pope Pope Gregory XIII (1572-1585) decided to use the statues for Piazza del Campidoglio, and the fragments were restored and reassembled. Since the head of the statue now on the left had not been found, a new one was made using the head of the other statue as a model. In 1582 the finished statues were placed on pedestals similar to the one Michelangelo had designed by for the statue of Marcus Aurelius. |

|

The Dioscuri statue on the right side

of the steps up to the Piazza del

Campidoglio. Both statues show

the twins wearing a pilos (πῖλος)

conical cap and a riding cloak. |

|

| |

The Dioscuri statue on the left side as you climb the steps up

to the Piazza del Campidoglio, on the Capitoline Hill, Rome. |

| |

|

|

|

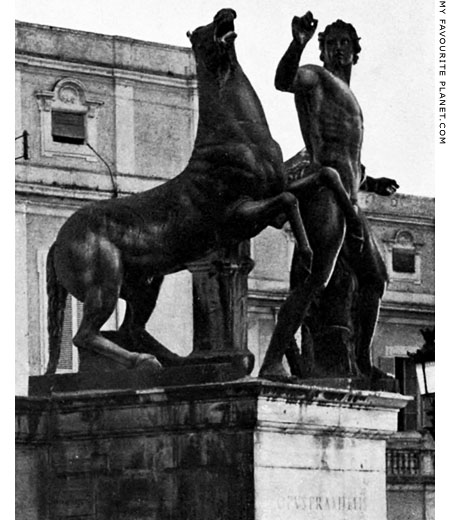

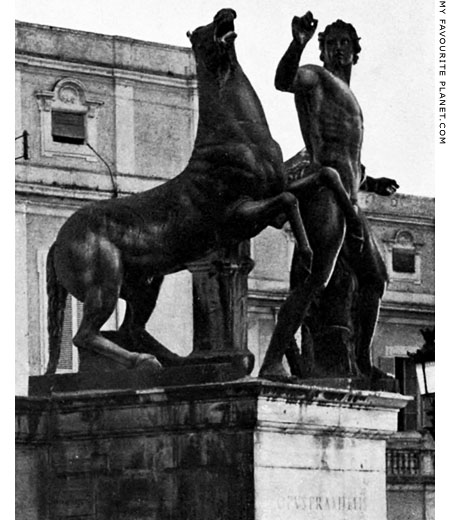

The statues of the Dioscuri on the Piazza del Quirinale, Quirinal Hill, Rome.

|

|

The two statues of Castor and Pollux with their horses, around 5.5 metres high, are thought to be Roman Imperial period copies of 5th century BC Greek originals. They stand on high pedestals in the middle of the square, flanking the Dioscuri Fountain and a 14.5 metre tall granite obelisk which previously stood in front of the Mausoleum of Augustus.

The statues, known as the horse tamers, had stood somewhere in the city since the fall of the Roman Empire, and during Medieval times were mentioned by authors and appeared in images of Rome. The false inscriptions on the pedestals, "Opus Phidiae" (work of Pheidias; statue in the left-hand photo) and "Opus Praxitelis" (work of Praxiteles; photo right), have been dated to circa 450 AD. They were discovered in the ruins of the early 4th century AD Baths of Constantine (Thermae Constantinianae) on the Quirinal Hill where they may have stood in antiquity. It has recently been suggested that they may have originally been set up at the entrance to the Temple to Serapis built by Emperor Caracalla (reigned 198-217 AD). This may also help explain why the heads of the two, much restored statues resemble portraits of Alexander the Great, since Caracalla developed an obsession for the Macedonian king (see Alexander the Great).

Pope Sixtus V (pontificate 1585-1590) commissioned Domenico Fontana to set the statues up on the square in 1588 and the hill became known as "Monte Cavallo" after them. The obelisk was added by Pope Pius VI in 1786, and in 1818 Pope Pius VII moved the fountain's dark grey granite basin there from in front of the church of S. Maria Liberatrice in the Forum Romanum, where it had been used as a cattle trough.

Photo source: Edmund von Mach (editor), University prints. Series A: Greek and Roman sculpture; 500 plates to accompany a handbook, plate A 129. University Prints, Boston, Mass., 1916. At the Internet Archive. |

|

| |

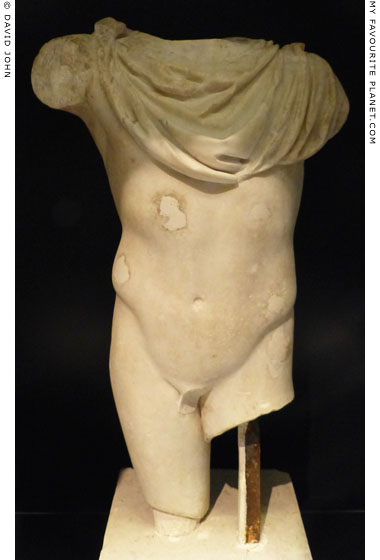

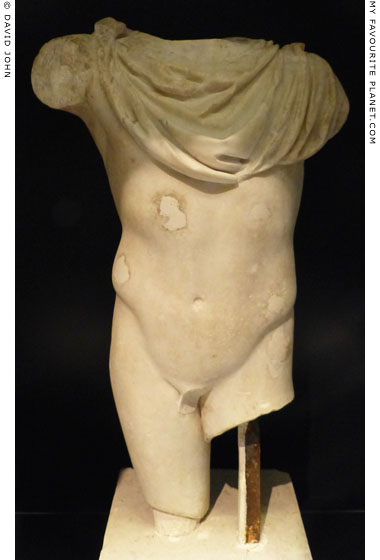

The torso of a marble statuette of a youth wearing a

cloak over his chest and shoulders. Perhaps one of the

Dioskouroi or Hermes (see similar statues of Hermes).

Probably 1st half of the 2nd century AD.

Height 60 cm, width 33 cm, depth 19.5 cm.

Skulpturensammlung, Albertinum, Dresden. Inv. No. Hm 249. |

| |

A marble statue of a warrior, perhaps one of the Dioskouroi.

Roman period, 200-1 BC. Found in the

sea off the coast Marsala, west Sicily.

The naked figure carries a small round shield and a military

cloak on his left arm and a sword belt across his chest.

Lilibeo-Baglio Anselmi Regional Archaeological Museum, Marsala. Inv. No. 4583. |

| |

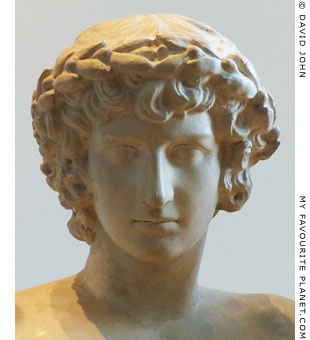

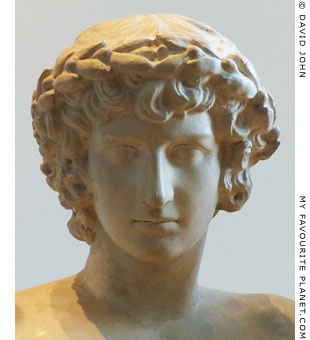

Plaster cast of the "San Ildefonso Group", marble staues of two youths,

perhaps the Dioscuri. The head of the figure on the left has been

replaced with a portrait of Antinous of the Apollo-Antinous type.

Augustan and Hadrianic periods, 1st century BC - 2nd century AD.

Height 160 cm, width 112 cm, depth 58 cm.

Abguss-Sammlung (Cast Collection), Semperbau, Dresden. Inv. No. ASN 2379.

Acquired in 1783 with the cast collection of Anton Rafael Mengs (1728-1779).

|

The original statue group, made of white Carrara marble, is in the Museo del Prado, Madrid (Inv. No. 28-E). Also known as the Ildefonso Group, it was named after San Ildefonso in Segovia, Spain, where it was kept at the palace of La Granja until 1839 when it was acquired by the Prado.

Probably found in the early 17th century in Rome, the earliest record of the sculpture is in 1623 when it was in the collection of Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi at the Villa Ludovisi, Rome. After the cardinal's death it became the property of Cardinal Camillo Massimo, then of Queen Christine of Sweden, and in 1724 it was acquired by King Felipe V of Spain.

It is thought that the sculpture was made during the reign of Augustus (27 BC - 14 AD), and at some point the head of the youth on the left was replaced by a portrait of Antinous, Emperor Hadrian's deified favourite. This may have occurred either during Hadrian's reign (117-138 AD) or, more probably, when it was restored around 1623 by Ippolito Buzzi (1562-1634).

There is no other known statue group of this type, which is thought to be a Neo Attic creation inspired by works of 5th and 4th century BC Greek sculptors such as Polykleitos and Praxiteles. However, a late 1st century BC statuette in Athens is clearly a version of one of the right-hand figure of the group (see photo below). It has been suggested that the group may be a work by Pasiteles or his school.

Two idealized nude youths, wearing laurel wreaths, stand next to each other. The figure on the left leans on the other who holds two torches, with one of which he ignites a garlanded altar. The youths have been variously identified as Castor and Pollux, Orestes and Pylades, Hypnos and Thanatos (Sleep and Death), and Corydon and Alexis.

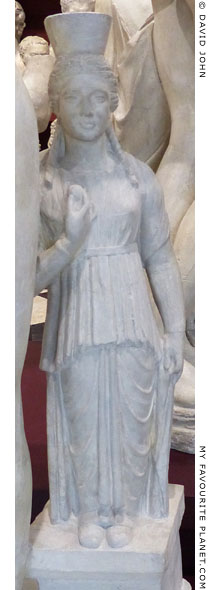

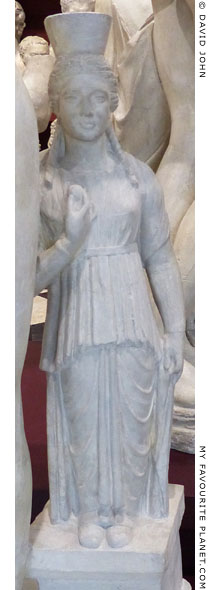

Behind the right-hand figure stands a small Archaistic female figure (see photo, below right) wearing a polos and a peplos, thought to be a statue of a goddess, perhaps Persephone or Artemis. Her right arm is bent, and in her raised right hand she holds a small round object, interpreted as an egg or a pomegranate, to her breast.

Although I have so far seen no other reference to this idea, I am reminded of figures of Helen of Troy wearing a polos or kalathos on reliefs depicting her standing between her brothers, the Dioskouroi (e.g. Sparta Archaeological Museum, Inv. Nos. 201, 202 and 203; see also reliefs of the Dioskouroi and Helen below). As mentioned above they were all said to have been born from eggs. Similar figures appear, for example, on the 2nd century AD "Leda sarcophagus" (see below), found in Kephissia, Attica. The relief on the left side of the sarcophagus depicts Leda and the swan (Zeus), and on the front Helen stands between the Dioskouroi. Each of the four figures on the corners, referred to as Caryatids or Helen-statues, wears a polos (or kalathos), peplos and hairstyle very similar to that of the San Ildefonso figure. They stand in the same pose, holding a small object between the forefinger and thumb of one hand which is pressed against her breast, while her other lowered hand clutches at the side of her garment.

See drawings and photos of the "Leda sarcophagus", as well as photos of two of the Spartan reliefs of the Dioskouroi and Helen:

Ellen E. Perry, Iconography and the dynamics of patronage: a sarcophagus from the family of Herodes Atticus. In: Hesperia, Volume 70, Issue 4 (October - December 2001), pages 461-492, particularly pages 474-475, figures 1 and 3 (Caryatids on the "Leda sarcophagus"), 6 and 7 (Spartan reliefs). American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA). At jstor.org.

A large number of casts and copies in various materials (bronze, marble, cast iron, porcelain) have been made of the San Ildefonso Group, and many are now in collections and museums.

The Dresden cast is well finished and polished, and is in remarkably good condition considering its history. It has been transported a number of times, and has survived the World War II bombings, confiscation by the Soviet army and the flooding of the River Elbe in 2002.

Until 2016 it was exhibited with the Sculpture Collection (Skulpturensammlung) in the Albertinum, Dresden (where the photo above was taken), but is presently (2018) displayed with other casts of ancient sculptures in a room in the Semperbau (or Semper-Galerie) of the Zwinger, which exhibits paintings of the Old Masters (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister). The cast collection as well as the antiquities collection of the Dresden museums have been without a permanent home since 2002, although there are plans to house them in part of the Semperbau in the near future.

For further information about the Dresden Cast Collection

and Mengs, see the Niobe page. |

Head of Antinous of the Apollo-Antinous type

on the San Ildefonso Group cast in Dresden. |

| |

The small female figure of the

San Ildefonso Group in Dresden. |

| |

| |

A marble statuette of a youth

of the Ildefonso type.

Around the end of the 1st century BC.

Provenance unknown.

"Probably Pentelic marble".

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 3631. |

|

Anonymous engraving of the San Ildefonso Group,

published by Johann Winckelmann in 1767. The

print was produced after the group was sent to

Spain, and the original drawing may have depicted

a plaster cast, made around 1687-1706, which

stood in the French Academy in Rome.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Monumenti

antichi inediti spiegati ed illustrati da

Giovanni Winckelmann, Volume I (Unedited

antique monuments, described and illustrated

by Giovanni Winckelmann). An unnumbered plate

in the preface, between pages XIII and XIV.

Rome, 1767. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

| |

A relief of the Dioskouroi and their sister Helen of Troy on the front of the "Leda sarcophagus",

an Attic marble sarcophagus in Kifissia, northeast of Athens. Mid 2nd century AD.

|

Known as the "Leda sarcophagus", this is the largest of four sarcophagi in a marble tomb discovered in September 1866 near the church of Agia Paraskevi (used as a mosque, then a barracks, later demolished) on Platanos Square (Πλατεία Πλατάνου, Plateia Platanou), Kifissia, northeast of Athens. The sarcophagi are now displayed in situ in a small, purpose-built building. The area is thought to have been part of the estate of Herodes Atticus and Annia Regilla, and the sarcophagi the graves of four of their six children who died at a young age. This sarcophagus may have been made for Elpinike (Ἐλπινίκη), their second child and first daughter.

Sarcophagus height 112 cm; length 227 cm (front), 233 cm (back);

width 94 cm (left side), 89 cm (right side). [20]

The fragmentary gabled lid currently on the sarcophagus does not belong to it, and the original lid was probably a kline sculpture, depicting one or more figures lying on a kline (couch). Such sculptures usually depict the deceased (see an example of a kline sculpture on a Roman sarcophagus below, and on Etruscan cinerary urns in Homer part 2), and in this case may have been a portrait of Elpinike, and perhaps also her husband. A marble fragment of a reclining female figure (now missing) found in the tomb was probably part of the lid.

On the front is a relief of the Dioskouroi standing either side of their sister Helen of Troy. The twins are almost mirror images, arranged symmetrically, standing frontally with their heads turned towards Helen in the centre. In the lowered inner hand each holds an upturned, sheathed sword by its hilt, and the raised outer arm originally held a metal spear which was probably stolen by grave robbers. The figures stand in a contrapposto pose, with the weight resting on the outer leg and the other slightly bent. Each is naked apart from a fillet (headband) and a cloak which covers the chest and shoulders, and hangs to behind the mid calfs. On both figures the cloak is fastened at the right shoulder.

Helen faces frontally, with her head turned slightly to her left. She wears a fillet, a long, sleeved chiton girdled at the waist, and a himation (cloak), which rests on her shoulders, with the lower right side crossing in front of her lower torso and draped over her raised left forearm. In her left hand she holds a small object, perhaps an apple or a pomegranate.

The Classicistic relief on the left side of the sarcophagus depicts Zeus, disguised as a swan, attempting to copulate with a nude Leda (see image, above right), who appears to be trying to fend him off. His successful seduction or rape resulted in the birth of Helen and at least one of the Dioskouroi. Instead of webbed feet the huge swan has the talons of a bird of prey, presumably an eagle, a symbol of Zeus. This work has been compared to reliefs of Leda and the swan from Brauron (Athens National Museum, Inv. No. 1499) and Argos (British Museum, Inv. No. 1973,0302.1, Sculpture 2199).

On the right side is a relief of winged infant Eros stringing his bow, perhaps as a prelude to the erotic scene on the other side. The figure is of a type known from a number of other sculptures. The relief on the back shows a Nereid riding on the tail of a Triton.

At each of the four corners of the sarcophagus a "Caryatid", perhaps representing a statue of Helen (see above), stands on a statue base. The top of each figure's polos touches and appears to be supporting the upper moulding of the casket, in the way that Caryatid statues were used as columns to support the roofs of buildings (see, for example, the Caryatids of the Erechtheion on the Athens Acropolis). In this case, the moulding represents the frame of the kline, and the Caryatids its legs. Each figure wears a polos (or kalathos) and peplos, and holds a small object between the forefinger and thumb of one hand which is pressed against her breast. Her other lowered hand holds the side of her garment. The Caryatids at the edges of the front of the sarcophagus are mirrored for the sake of symmetry, so that the figure on the left holds the object in her right hand, and that on the right has it in her left hand. On the back the relative positions are reversed.

As is often the case with such reliefs, those on the front and two sides have been considered to be copied from or influenced by statues. The composition and frame of the Triton relief suggest that it may have been modelled on a two-dimensional work, perhaps a relief, painting or mosaic.

See: Ellen E. Perry, Iconography and the dynamics of patronage: a sarcophagus from the family of Herodes Atticus. In: Hesperia, Volume 70, Issue 4 (October - December 2001), pages 461-492. American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA). At jstor.org.

Drawings of the sarcophagus made in Autumn 1886 by the Swiss artist and archaeological draughtsman Émile Gilliéron (1851-1924).

Source of drawings: Carl Robert (1850-1922), Die antiken Sarkophag-reliefs Band II, Mythologische Cyklen, No. 9, pages 9-10 and Tafel III, 9 and 9a. G. Grot'esche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin, 1890. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

The discovery of the tomb was first published in: Otto Benndorf, Römishes Grab in Kephisia. In: E. Hübner (editor), Archäologisher Zeitung 26, pages 35-40 (Tafel 5, 2). Georg Reimer, Berlin, 1868. At the Internet Archive. |

An early photo of the right-hand Dioskouros on

the front of the "Leda sarcophagus" in Kifissia.

Source: Carlo Anti, Lykios, Fig. 8, page 32. In:

Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica

Comunale di Roma, Anno 47 (1919), pages

55-138. P. Maglione & C. Strini, Rome, 1921.

At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

Leda and the Swan on the left side of

the "Leda sarcophagus" in Kifissia. |

| |

| |

The myth of Leda and the Swan on a limestone block from a frieze sculpted in high relief.

In the centre, Leda is seen from behind, nude, holding the Swan (Zeus) by the throat

with her left hand. The bird has its left foot on her right calf. to the left of Leda is the

head of a bearded male, perhaps Zeus (or Tyndareos?). To either side of her stands

a Nymph holding an egg, symolizing the conception of Leda's children, Clytaemnestra,

Helen, Kastor and Pollux. In early Christian Egypt this pagan myth remained a popular

motif for memorials to fertile married women.

Around 400-500 AD, Late Roman period. Probably from a woman's tomb at Oxyrhynchus, Egypt.

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Inv. No. AN1970.403. |

| |

Inscribed votive relief of Helen (of Troy) standing between the two mounted Dioskouroi.

Found in 1928 near a Byzantine chapel in the area of the necropolis of Thasos, Macedonia,

Greece. According to the inscription, roughly incised above the heads of the three figures,

the relief was dedicated by Pola, daughter of Herakleides.

Πόλα Ἡρακλίδου εύχήν

Late Hellenistic period. Height 30 cm, width 45 cm.

Thasos Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 22.

|

The relief shows the Dioskouroi on horseback, each with the outer arm (which may have held a spear) raised, and facing a woman in the centre, standing at an altar. It is thought that she may be their sister Helen. Two cockerels stand on either side of her, below each of the horses.

The popularity of the Dioskouroi on the northen Aegean island of Thasos (Θάσος) may be due to the influence of Paros, which colonized the island around 680 BC (see History of Kavala). The annual Dioskouria festival included public feasts (symposia). The main Dioskouroi sanctuary of Thasos is thought to have been at a location known as Patargia (also referred to the "Plain of Patargia"), the area of the necropolis, outside the southern city walls, where this and other reliefs depicting the twins with a woman, perhaps Helen, have been discovered (e.g. Thasos Archaeological Museum, Inv. Nos. 145 and 1286). At Alyki (Αλυκή), on the southeast coast of the island, a sanctuary built between the 6th and 5th centuries BC may also have been dedicated to the twins. Graffiti inscriptions found there are prayers to the Dioskouroi for "salvation from the dangers of the sea" and "safe voyages".

Similar reliefs depicting the Dioskouroi with a female figure, probably Helen, have been found at a number of other locations, including Sparta, Amphipolis (see below) and Telmessos. They may have been worshipped at these places as a triad. Helen was included in the worship of the Dioskouroi at many of their sanctuaries, particularly at Sparta (perhaps from the 2nd or 1st century BC), and it has been suggested that in some places she may have become syncretized (amalgamated) with a local deity.

Pausanias mentioned an ancient image of Helen between the Dioskouroi among several mythological scenes on the "chest of Kypselos" (or "chest of Cypselus"), a richly decorated Archaic cedar-wood chest dedicated by the Corinthians, in the Temple of Hera, Olympia (see the description of the chest in Homer part 2).

"On the chest are also the Dioscuri, one of them a beardless youth, and between them is Helen."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 19, section 2. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

| |

An unlabelled limestone relief outside Amphipolis Archaeological Museum depicting

two horsemen, each wearing a pilos, cloak and short chiton (χιτών, tunic), either

side of a woman with her right arm raised. Perhaps the Dioskouroi and Helen.

Amphipolis (Ἀμφίπολις) in Thrace was colonized by Athens in 437 BC, but captured by the Spartan

general Brasidas in 424 BC, during the Peloponnesian War (see History of Stageira part 5).

The Spartan influence on the culture of the city may explain the iconography of the relief.

Amphipolis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ834.

See another relief of the Dioskouroi from Amphipolis below. |

| |

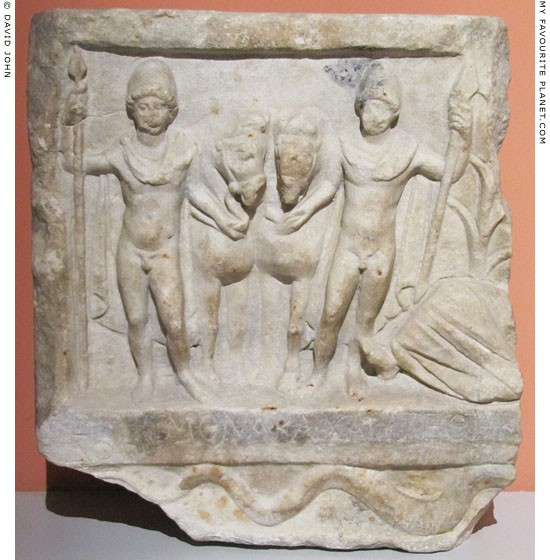

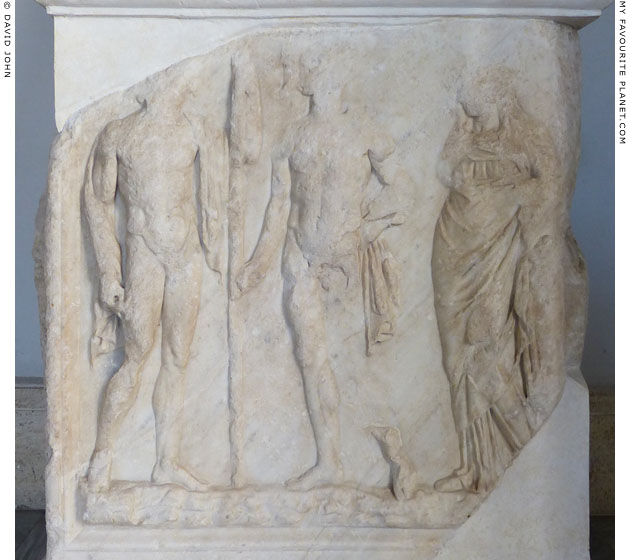

Bottom part of a fragmentary inscribed votive relief with a depiction of the Dioskouroi as

Roman infantry men. They stand facing frontally, either side of a female figure, who stands

on a plinth or altar on the front of which the name MANTA is inscribed. Manta was the local

variation of Helen, the sister of the twins, who was worshipped together with them. The top

of the relief and the head of the figures are now missing. The Latin inscription at the bottom

of the relief is now illegible, but the words Dioscuris and Manta can still be discerned.

Found in Drama (Δράμα), East Macedonia, Greece.

2nd - 3rd century AD, Roman Imperial period.

Drama Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. Λ 97. |

| |

Detail of an Etruscan bronze mirror with incised decoration depicting three figures,

interpreted as three of the Cabeiri (Κάβειροι, Kabeiroi), also known as "the Great

Gods" (Μεγάλοι Θεοί, Megali Theoi). The Dioskouroi were known to the Etruscans

as Kastur and Pultuce, and together as the Tinas Cliniiaras (Sons of Tinia, the

Etruscan equivalent of Zeus). They sit either side of an unidentified deity in a

temple, indicated by an Ionic column and part of an architrave.

Mid 3rd - early 2nd century BC. Diameter 13 cm, length (including handle) 27cm.

Civic Archaeological Museum, Milan. Inv. No. A 0.9.1002.

From the Ancona Collection, then the Seletti Collection. |

| |

Fragmentary marble statue base with a relief of the Dioscuri with their sister Helen of Troy.

30-20 BC, Roman period copy of a 4th century BC original.

The side of the base to the left has part of a relief of Helen standing

in front of their mother Leda (see photo below). The Hellenistic statue

of Juno/Hera known as the "Juno Cesi" now stands on the restored base.

Sala del Galata (Hall of the Gaul), Palazzo Nuovo,

Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 1961. |

| |

Fragmentary relief of enthroned Leda with Helen of Troy

on the left side of the statue base above. |

| |

An Egyptian sandstone votive stele with a relief of the Dioscuri on horseback.

The two figures are mirror images, each wearing armour, holding a spear in the outer

hand and with a star above his head. Between them is the full figure of the Egyptian

falcon-headed god Horus (the moon god Khonsu has also been suggested). At the centre

above the frame of the main relief is the Egyptian sun-disk symbol with two serpents.

Late Hellenistic or early Roman Imperial period. Place of origin unknown. Purchased in Egypt

in winter 1900-1901 by the Italian Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaparelli (1856-1928), director

of the Museo Egizio di Torino, 1894-1901. Height 53 cm, maximum width 52 cm, depth 9 cm.

Museo Egizio, Turin. Inv. No. S. 01321. [21] |

| |

A marble votive relief with the Dioskouroi and a procession of worshippers.

Palazzo Altemps, National Museum of Rome. Inv. No. 182595. Brancaccio Collection.

|

On the left, Castor and Pollux sit on rock-hewn seats holding spears, with their horses at their sides. They face right, towards an approaching woman holding a wine jug and a phiale (libation bowl). Behind her a family of worshippers, a man and a woman holding ceremonial branches and two boys, depicted at a smaller scale, also approach the twins. The inscription below the relief is modern, museum labelling in stone.

The composition is based on a common type of Attic votive relief (see similar reliefs dedicated to Asklepios, Pan and the nymphs, Demeter, and Plouton and Persephone) and it is thought this may be a Greek original of the first half of the 4th century BC. Found in the area of the Horti Maecenatiani (Gardens of Maecenas), Rome, it may have belonged to a Roman collector. |

|

| |

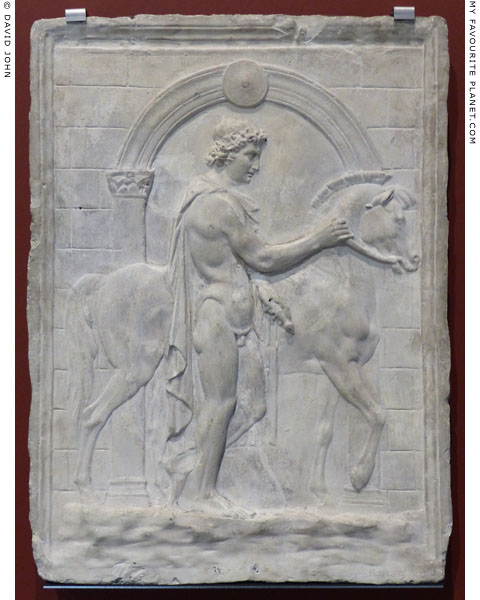

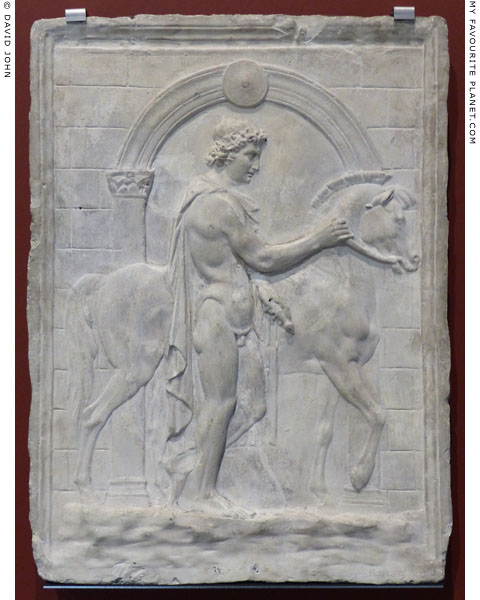

Plaster cast of a marble relief of one of the Dioscuri (a Dioskouros

or Dioscurus) leading a horse to the right, past an arched gateway.

The original is from the Roman Imperial period.

Height 82 cm, width 62 cm, depth 6 cm.

Abguss-Sammlung (Cast Collection), Semperbau, Dresden. Inv. No. ASN 4406.

|

So far I have discovered little about the original relief, which may be a Neo Attic work and is of fine quality. It is in the Pio Clementino Museum of the Vatican Museums, Rome, and according to the Dresden museums website is of the "middle of the Imperial period", presumably the 2nd century AD.

One of the 19th century catalogues of the Dresden Cast Collection describes the relief as "Castor with the horse" (Matthäy, 1831, Hautreliefs im fünften Fenster, Cat. No. 91, page 29). Two others claim it depicts Bellerophon with Pegasus before gates of Corinth (Chalybaeus, 1843, Reliefs im fünften Fenster, Cat. No. 52, page 37; Hettner, 1881, Cat. No. 139, page 105), although the horse does not appear to have wings.

For further information about the Dresden Cast Collection and

details of the catalogues see the note on the Niobe page.

For further information about Bellerophon and Pegasus