|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > People > Demeter and Persephone |

|

back |

Demeter and Persephone - Part 1 |

|

Part 1 of 2 |

|

|

| |

Demeter and Persephone

Part 1

The mother goddess Demeter (Δημήτηρ), the daughter of Cronus and Rhea and sister of Zeus and Hera, was one of the twelve Olympians, the major deities of the Greek pantheon. Her Roman equivalent was Ceres (the origin of the word cereal).

She was associated with harvests and credited with the gift of agriculture to humans. She was given the epiphets Sito (Σιτώ, She of the Grain) as the giver of corn, and Thesmophoros (Θεσμοφόρος, Law Bringer; from Θεσμός, thesmos, divine order, law, and φόρος, phoros, bringer, bearer) for her part in agricultural society in which civilization and the rule of law developed.

Along with her daughter Persephone (Περσεφόνη, she who destroys the light; to the Romans Proserpina), also known as Kore (Κόρη) and Despoina (Δέσποινα), the Maiden [1], who was abducted by Plouton (Πλούτον, also known as Pluto or Hades, ᾍδης or Ἁιδης), Demeter was associated with the underworld and the cycle of the seasons, life and death. In the Homeric Hymns she is referred to as "rich-haired Demeter, awful goddess", and "Queenly Demeter, bringer of seasons and giver of good gifts". [2]

As with other ancient Greek deities and mythological figures, the tales and traditions concerning Demeter and Persephone varied in different parts of Greece from prehistoric times, and the age, history and nature of their religious significance continue to be subjects of debate. And as ever, many theories have been developed, questioned and refuted. Even their names, attributes and roles in myths, as well their relationships to other deities, particularly Zeus, Poseidon, Plouton, Dionysus and Hekate, remain uncertain. The confusion is deepened by the deliberate secrecy which surrounded the cults of the chthonic (underworld) gods (for example at Samothraki) and the Eleusinian Mysteries.

The name Da-ma-te in Mycenaean Greek inscriptions, written in Linear B script, appears to refer to Demeter, and some scholars believe she may have even been a Great Goddess of Minoan religion. In modern times she has been seen as primarily an agricultural deity, worshipped by farmers as the goddess who taught humans the arts of crop-growing. However, the relationships of Demeter and Persephone to other deities as forces of nature above, on and beneath the earth, point to more essential, pre-agricultural questions of existence, such as the workings of nature, the cycle of the seasons and life beyond death.

The various stories, beliefs and practices from across the Greek world, with influences from other cultures, were adapted and developed over centuries or even millenia. The earliest literary mentions of Demeter and Persephone appeared from the time of Homer and Hesiod, and the Homeric and Orphic hymns, while most information is provided by writers of the Roman period, such as Pausanias.

The local stories of Demeter and Persephone differ in several details, but the generally accepted narrative of classical Greece is that Demeter was responible for seasonal growth and regeneration on the earth. Persephone was the virgin daughter of Demeter and Zeus, although in some places Poseidon was believed to be her father (see below). She was abducted by Plouton, perhaps with the collusion of Zeus, and taken to his underworld kingdom. Unaware of this, Demeter searched for her missing daughter above the earth without success, and as she grieved she neglected her duties; the progression of the seasons and the growth of plants ceased, and all life was threatened with extinction.

Eventually, Zeus intervened and sent Hermes to persuade Plouton to release Persephone. Plouton agreed, on condition that she returned to spend part of each year with him in Hades. According to some versions of the myth, Persephone ate, or was tricked into eating by Plouton, a number of pomegranate seeds on her return from the underworld, and was bound to remain there each year for one month for each seed eaten. On Persephone's return, Demeter once again allowed the seasonal growth to continue.

Thus Persephone represented the fecundity of the earth, and while she was above ground with her mother plant-life thrived, but during her period in the underworld growth ceased. Although the latter period has been thought by some to be winter, it may have been the dry summer months, when in Greece and around the Mediterranean many plants wither and die. Modern Greek farmers have to artificially water plants in summer, a luxury option unavailable to their ancient counterparts, and many of the crops which are now grown through the summer months, such as maize, tomatoes, tobacco and cotton, were not cultivated in ancient Greece.

According to other tales, while Demeter was searching for her daughter and in despair, she was offered hospitality in Eleusis by King Keleos (Κελεός) and Queen Metaneira (Μετάνειρα), in return for which the goddess taught their son Triptolemos (Τριπτόλεμος) the secrets of grain cultivation and sent him on a winged chariot with the mission of spreading the knowledge to humanity (see below and Part 2). Such stories also feature other characters included in the Eleusinian Mysteries, such as Demophon and Eubouleus (see Part 2).

Worship of Demeter and Persephone included a mystery cult, particularly popular among women, which had its most important centre at Eleusis, northwest of Athens (see below). Most of the details of the cult are unknown since initiates were sworn to secrecy. As the Greek historian Herodotus wrote of the Thesmophoria, the annual festival of secret rituals traditionally connected with fertility and marriage customs, and intially attended only by women:

"And of the mystic rites of Demeter, which the Hellenes call Thesmophoria, of these also, although I know, I shall leave unspoken all except so much as piety permits me to tell." [3]

Over 500 years later the travel writer Pausanias, when describing Eleusis, also declined to reveal details of the interior of the sanctuary or what went on there:

"My dream forbade the description of the things within the wall of the sanctuary, and the uninitiated are of course not permitted to learn that which they are prevented from seeing." [4]

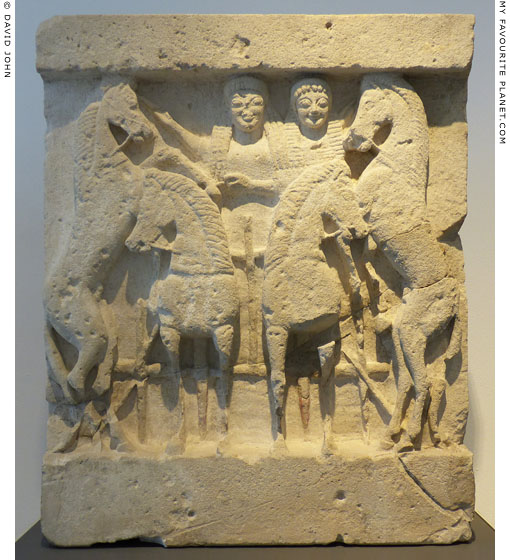

The cult spread throughout the Greek world from at least the Archaic period, and sanctuaries were established as far afield as Dion, Pella (see below) and Amphipolis in Macedonia, Megara Hyblaia and Selinous, Sicily, and particularly at Gela on the south coast of Sicily (see Part 2), an important cult centre. [5]

As in the case of other Olympian gods, Demeter's cult probably assimilated the worship of more ancient local deities such as the Phrygian mother goddess Kybele at the Greek cities of Anatolia (Asia Minor).

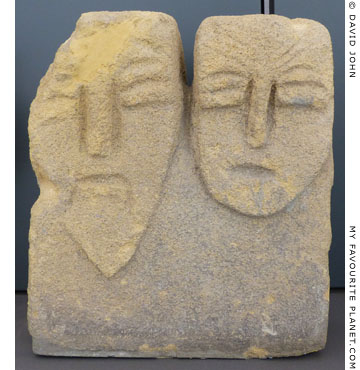

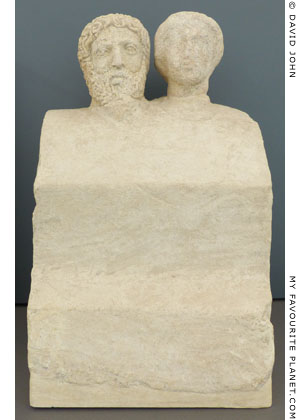

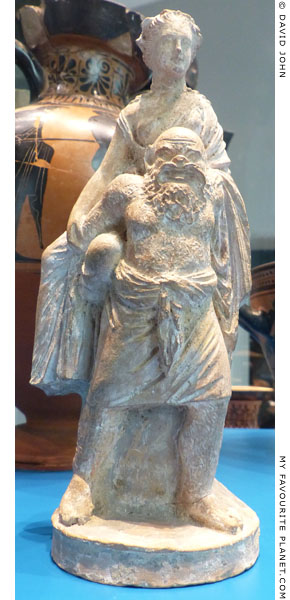

In myth and worship, Demeter and Persephone were in many cases inseparable, and of the many extant statues, figurines, busts and reliefs associated with their cult it is often impossible to say whether the mother or daughter is depicted due to the lack of distinguishing attributes.

Demeter is often shown seated (enthroned) with Persephone attending her, standing with a long torch. However, according to variations on the myth, Hekate took the place of Persephone while the latter was in the Underworld. Some representations of this scene have been interpreted as seated Artemis attended by Hekate (for example, a votive relief dedicated by Attic Launderers, see below).

"Hail, goddess, and save this people in harmony and in prosperity, and in the fields bring us all pleasant things! Feed our kine, bring us flocks, bring us the corn-ear, bring us harvest! and nurse peace, that he who sows may also reap. Be gracious, O thrice-prayed for, great Queen of goddesses!"

Callimachus (Καλλίμαχος, circa 310–240 BC), Hymn VI To Demeter, lines 134-138, translated by Alexander William Mair. In: Callimachus, Lycophron, Aratus, pages 125-135. English translations by Alexander William Mair and Gilbert Robinson Mair. Loeb classical Library. William Heinemann, London and G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1921. At the Internet Archive.

| |

References to Demeter

on My Favourite Planet |

| |

The sanctuaries of Demeter and Isis

in Dion, Macedonia, Greece:

Dion: the garden of the gods

at The Cheshire Cat Blog |

|

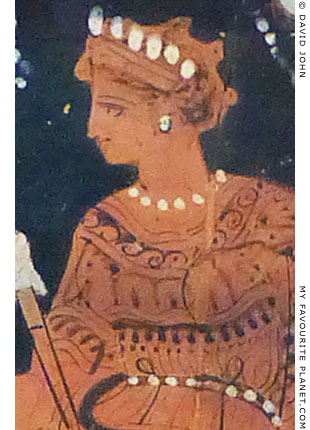

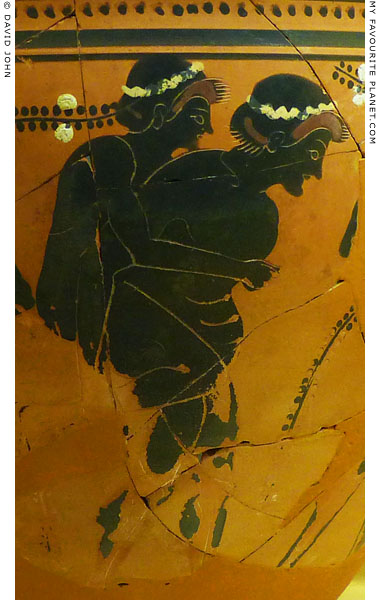

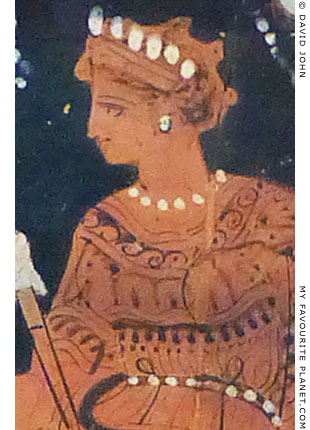

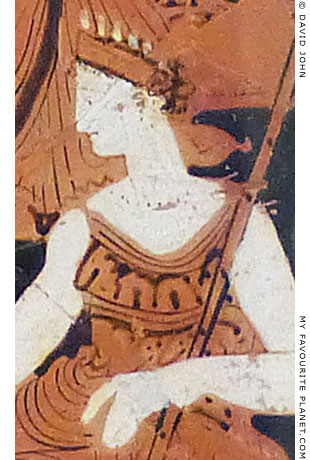

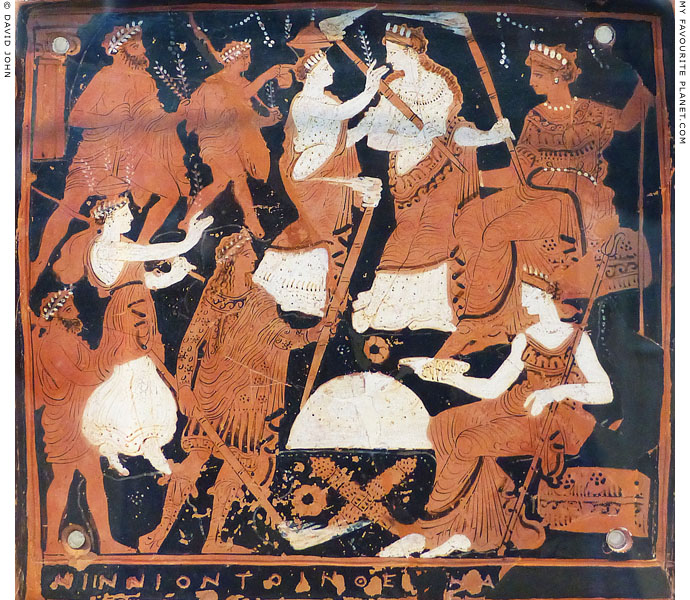

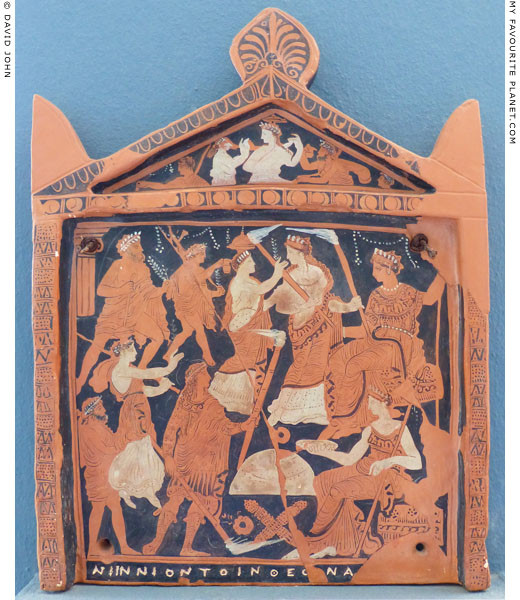

Demeter at the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Detail of the "Ninnion Tablet" from Eleusis.

See Further details below. |

| |

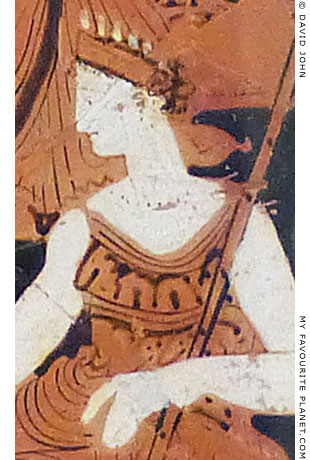

Persephone at the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Detail of the "Ninnion Tablet" from Eleusis. |

| |

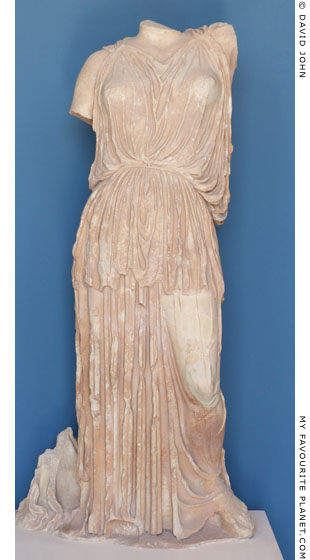

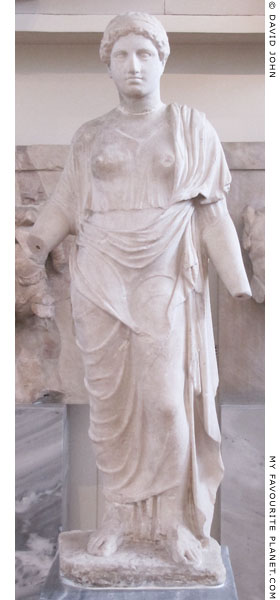

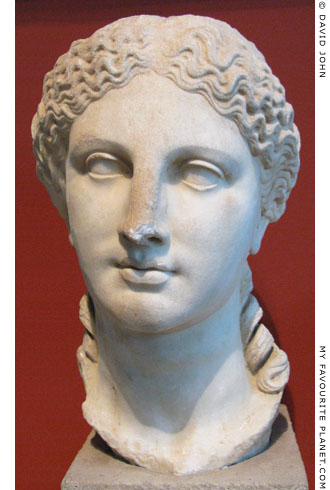

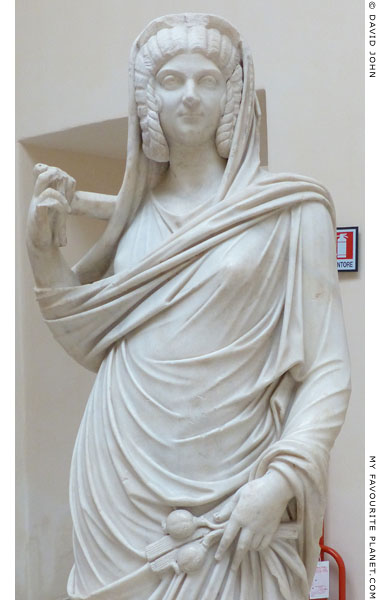

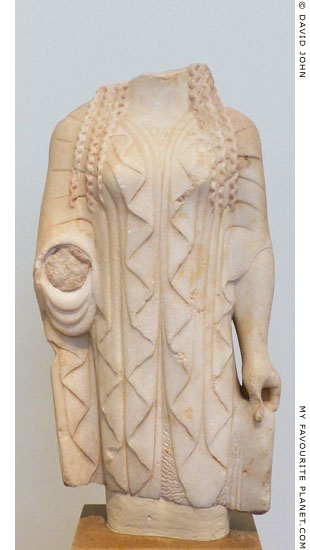

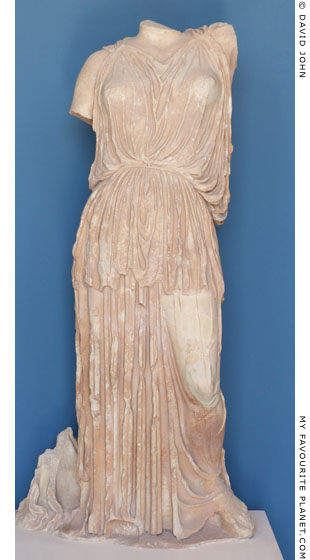

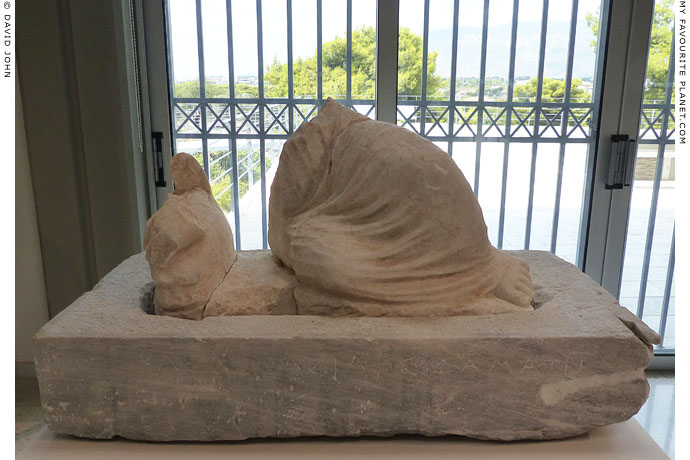

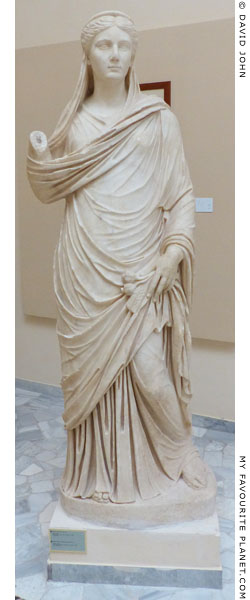

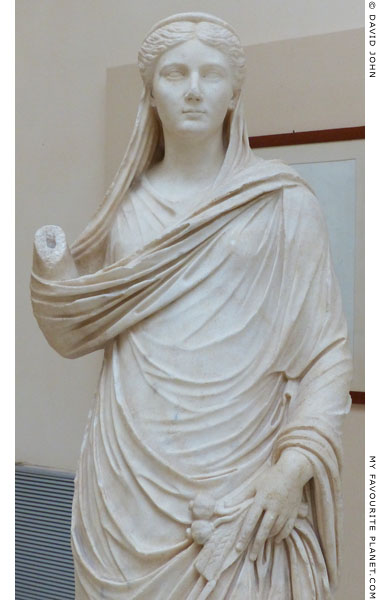

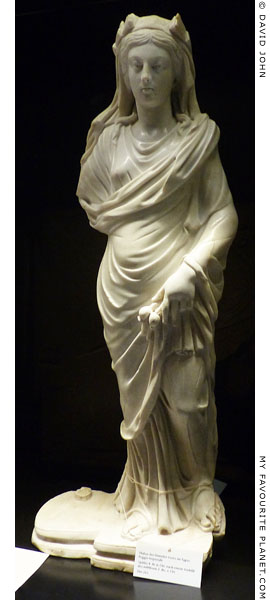

An over-lifesize marble statue of Demeter

from Eleusis. Thought to have made in

the workshop of Agorakritos of Paros,

circa 420 BC.

Pentelic marble. Height 180 cm.

The goddess wears a sleeveless Ionic

chiton and a Doric peplos, and was

probably lifting the edge of her peplos

over her left shoulder with her left

hand, as in the relief below.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 5076. |

| |

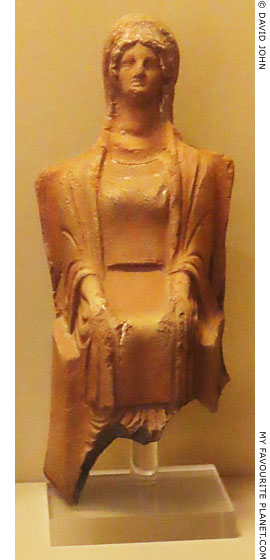

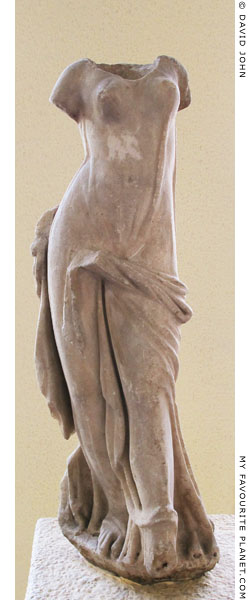

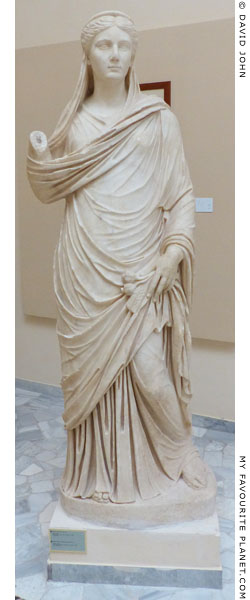

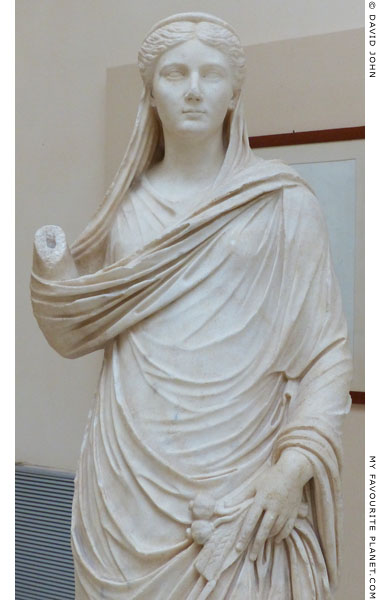

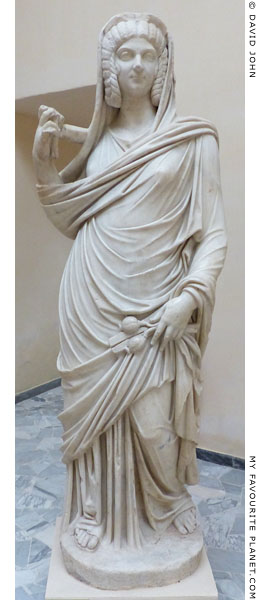

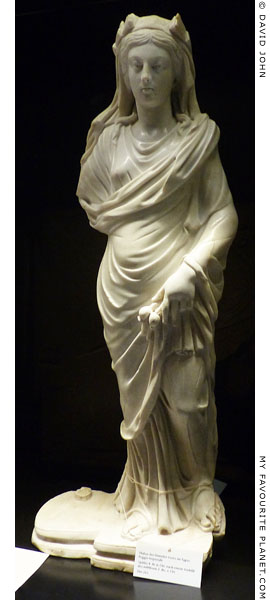

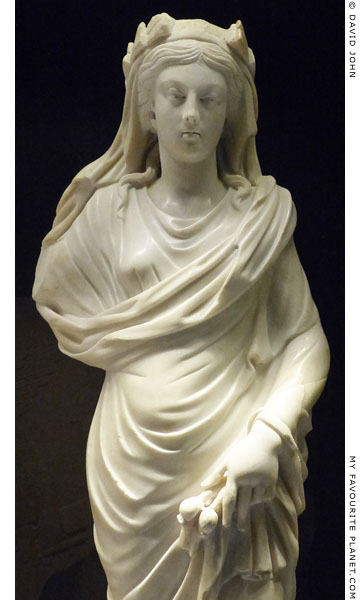

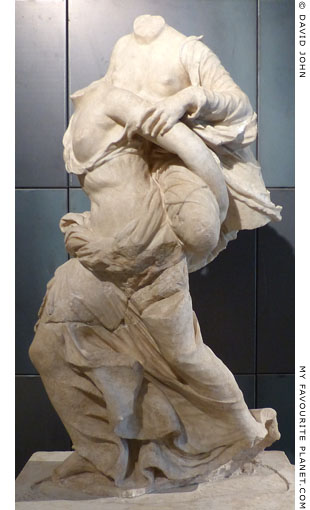

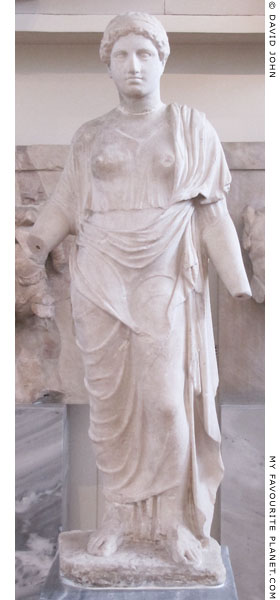

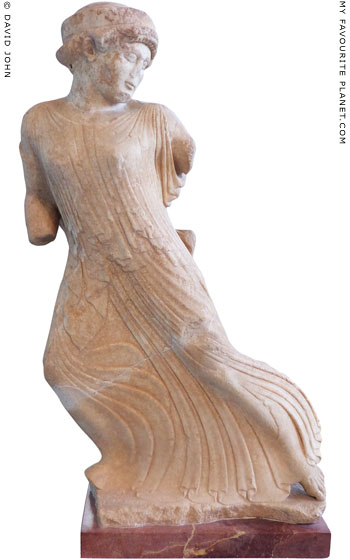

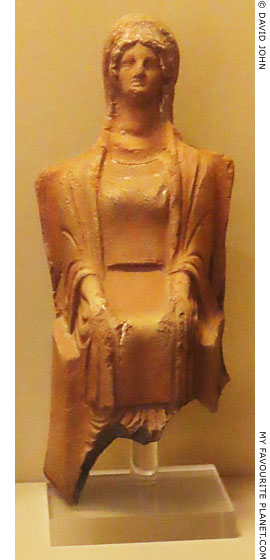

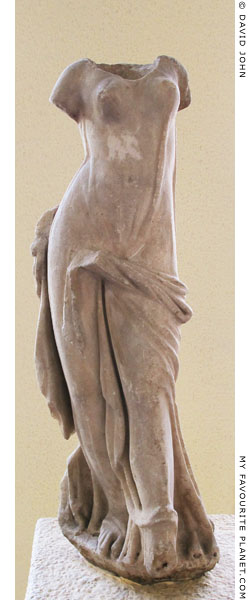

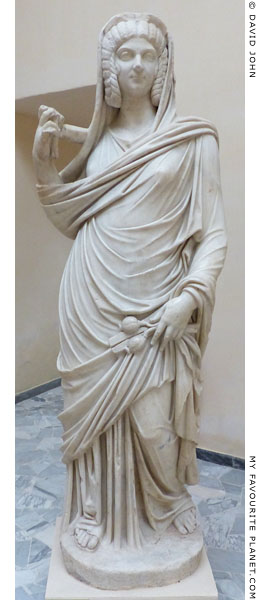

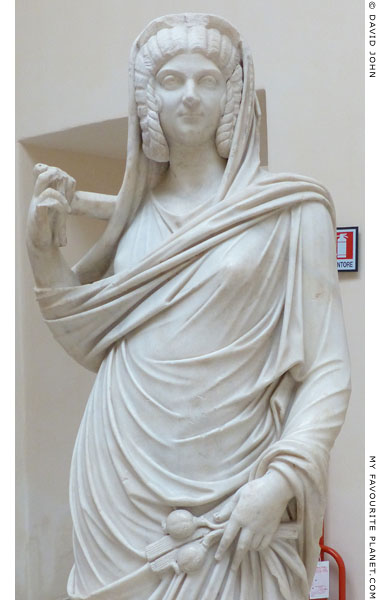

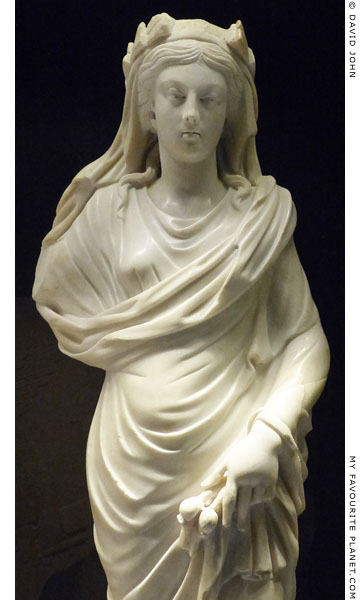

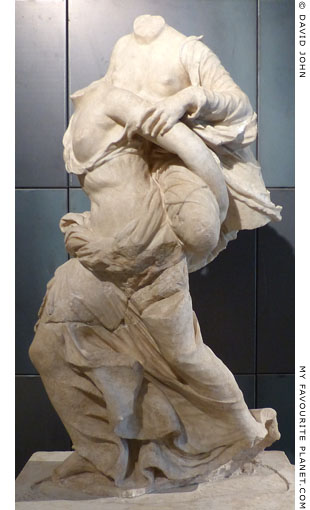

Marble statue of Persephone.

Pentelic marble. Work of the school of

Agorakritos of Paros, circa 420-410 BC.

Found on the hill of Mounychia, Piraeus.

The goddess would have originally

held a torch in each hand.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 176.

See more depictions of Demeter,

Persephone and related deities in

Demeter, Persephone Part 2. |

| |

| |

| |

Sanctuaries of Demeter and Persephone

Eleusis |

|

|

| |

Part of the seating area of the Telesterion in the Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis.

|

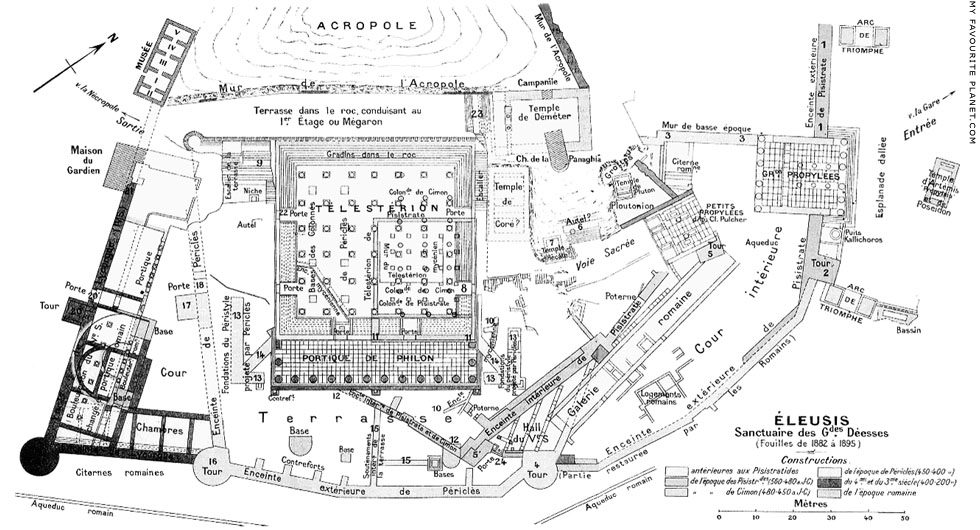

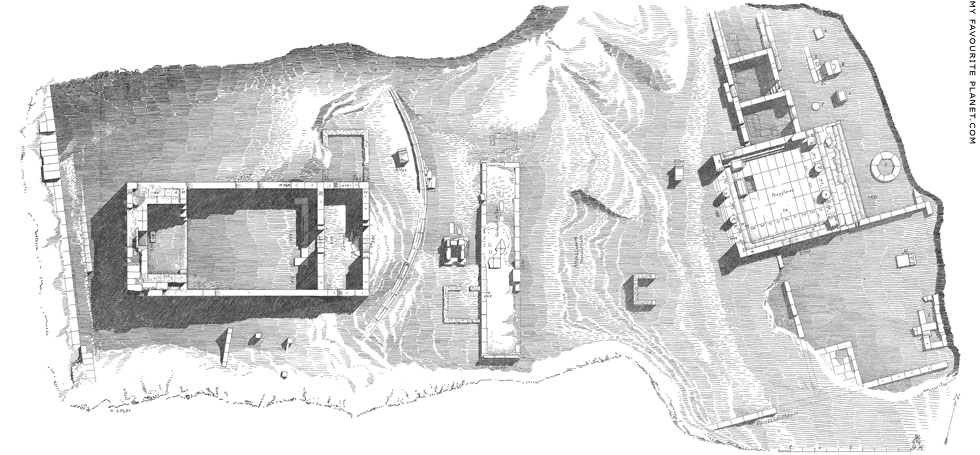

Eleusis (Ἐλευσίς; today Elefsina, Ελευσίνα), on the west coast of Attica, northwest of Athens, was the centre of the mystery cult of Demeter and Kore, and the main focus of the annual festival of the Greater Mysteries [6]. The Telesterion (Τελεστήριον, thank-offering for success), the temple of Demeter and Persephone, was an enormous hypostyle hall in which initiation to the Mysteries took place. According to ancient authors, the rituals of the initiation, which included the recital of sacred texts and the display of sacred objects (hiera) by the Hierophant (Ιεροφάντης, Revealer of Sacred Things), the high priest of the Eleusinian cult, produced a transcendental experience and encouraged a positive view of life after death.

"... among the many excellent and indeed divine institutions which your Athens has brought forth and contributed to human life, none, in my opinion, is better than those mysteries. For by their means we have been brought out of our barbarous and savage mode of life and educated and refined to a state of life and educated and refined to a state of civilization; and as the rites are called 'initiations', so in very truth we have learned from them the beginnings of life, and have gained the power not only to live happily, but also to die with a better hope."

Cicero (1st century BC), De legibus, 2.14.36.

The hall was gradually increased in size over centuries, and expanded around the Anaktoron, the original 7th century BC cult building. There were tiers of seating on all four sides of the hall from which initiates observed the rituals. In the photo above are the remains of the northwest corner of the building, with seats carved from the rock of the foot of the acropolis hill. The Roman architect and author Vitruvius (circa 80-70 - circa 15 BC) placed the Telesterion among four renowned temples of outstanding quality in the Graeco-Roman world, and named Iktinos (mid 5th century BC) and later Philon of Eleusis (mid-late 4th century BC) as two of the architects who enlarged the building.

"There are, in fact, four places possessing temples embellished with workmanship in marble that causes them to be mentioned in a class by themselves with the highest renown. To their great excellence and the wisdom of their conception they owe their place of esteem in the ceremonial worship of the gods ...

At Eleusis, the cella of Ceres and Proserpine, of vast size, was completed to the roof by Ictinus in the Doric style, but without exterior columns and with plenty of room for the customary sacrifices.

Afterwards, however, when Demetrius of Phalerum was master of Athens, Philo set up columns in front before the temple, and made it prostyle. Thus, by adding an entrance hall, he gave the initiates more room, and imparted the greatest dignity to the building."

Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, Book 7, Introduction. At Project Gutenberg.

The final building was destroyed by fire around 170 AD and was reconstructed by Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

See also:

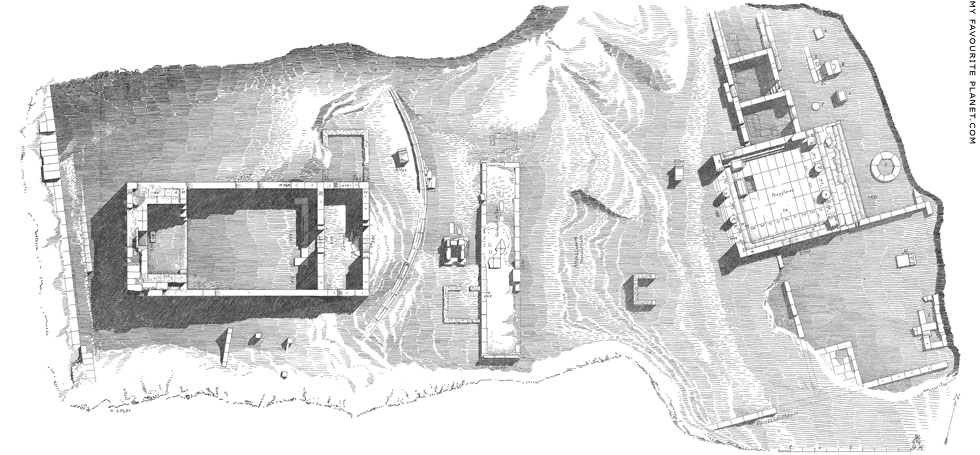

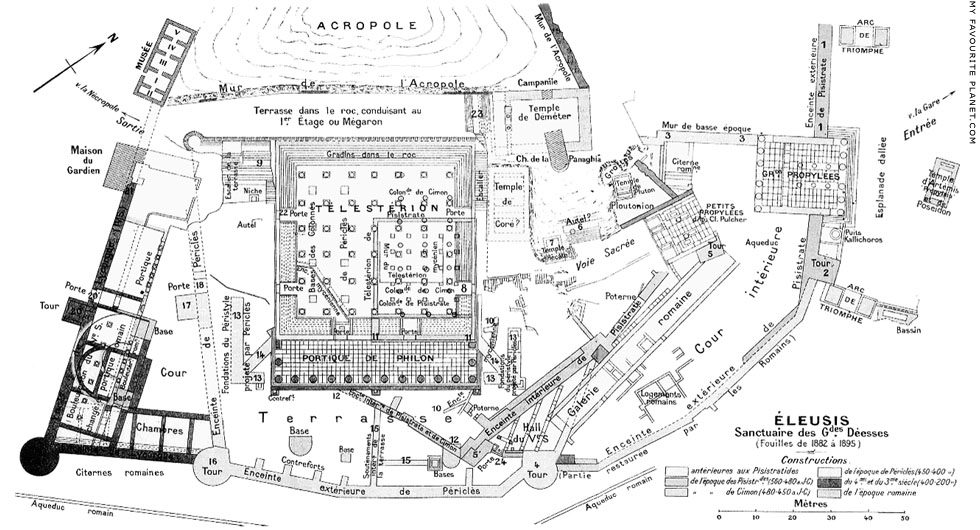

A plan of the Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis below.

The "Ploutonion" at Eleusis in Part 2. |

|

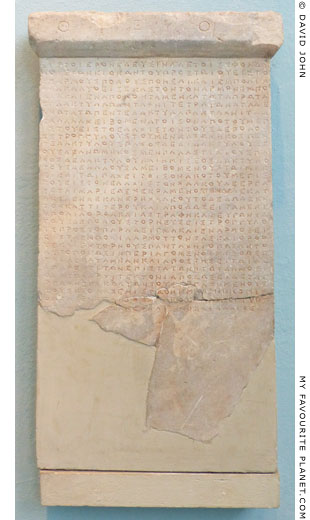

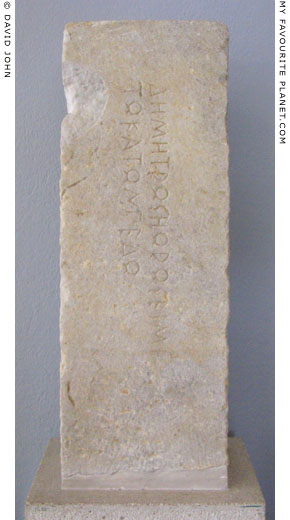

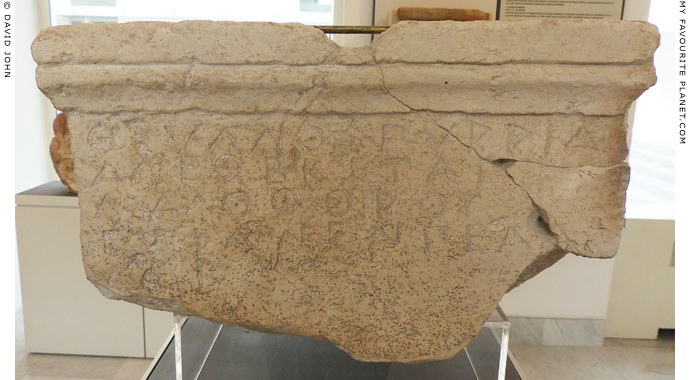

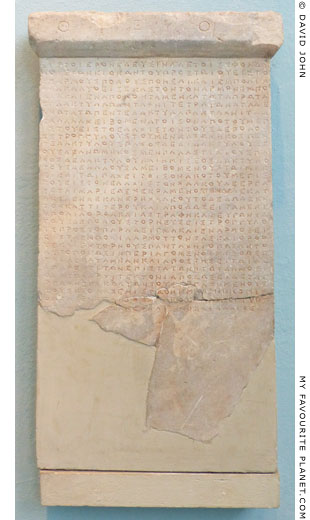

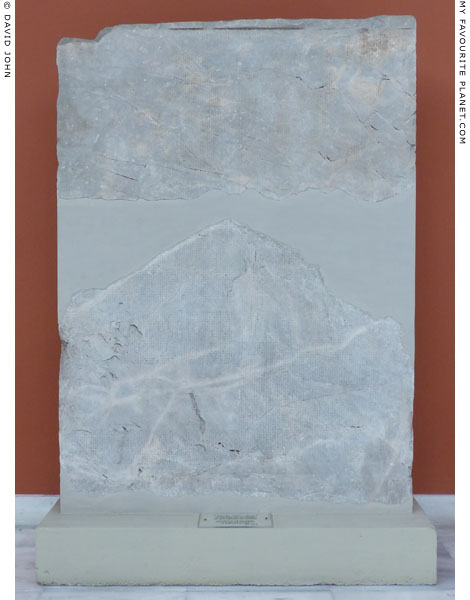

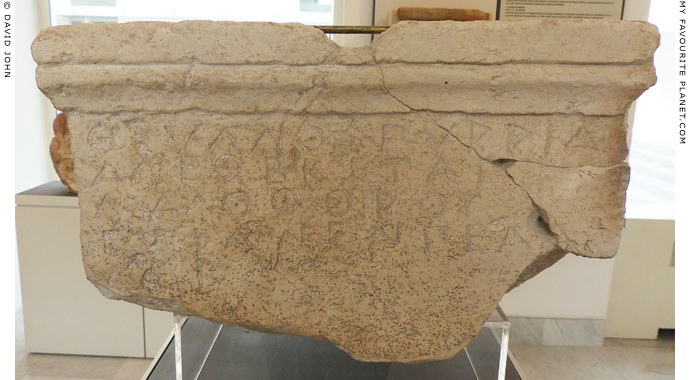

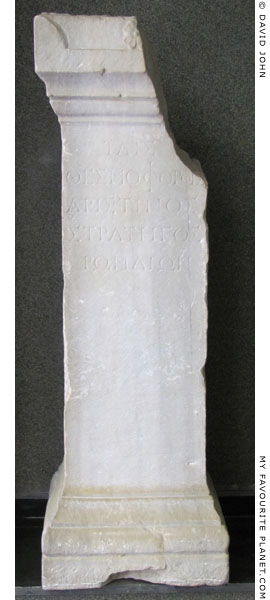

Three fragments of a stele of Eleusinian

marble with an inscription referring to

the manufacture of bronze dowels (poloi

and empolia) for the columns of the Stoa

of Philon (or Philonian Stoa).

Circa 336 BC. Found in Eleusis in 1893

by Demetrios Philios [see note 8].

Eleusis Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 5040.

Inscription IG II² 1675 (I.Eleusis 157). |

|

| |

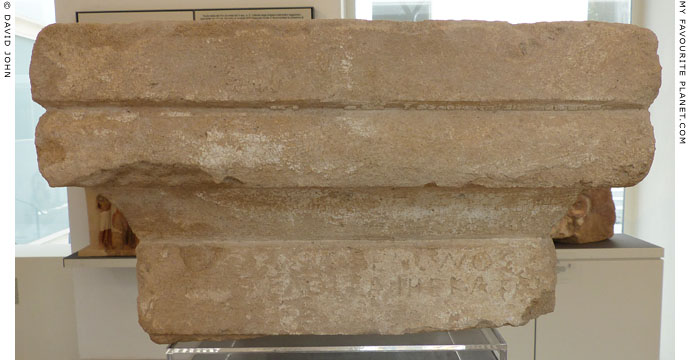

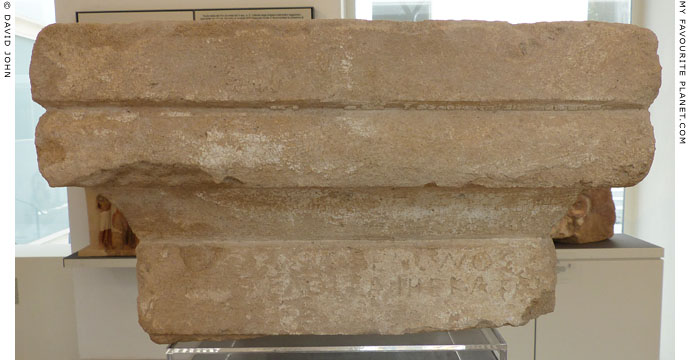

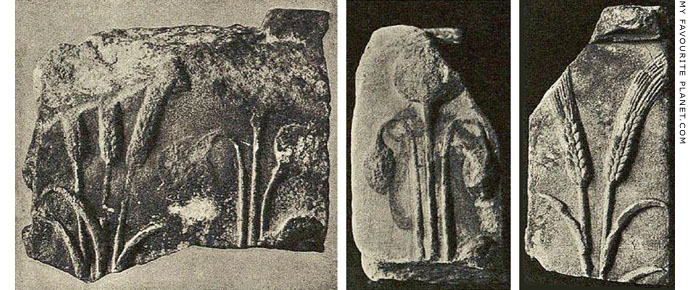

Part of the inscribed marble entablature of the outer facade of the Lesser Propylaia,

the inner gateway of the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis, built circa

50-48 BC, late Roman Republican period.

Eleusis archaeological site. Inv. No. 1039. Inscription: Corpus inscriptionum latinarum I 619.

|

The Roman period Lesser Propylaia, protected by a fortification wall, replaced the Archaic north gate, the main entrance to the sanctuary, built in the 6th century BC during the Peisistratid period. The sanctuary was later extended northwards to the Greater Propylaia (an exact copy of the central section of the Propylaia of the Athenian Acropolis), built by Emperor Marcus Aurelius (reigned 169-180 AD).

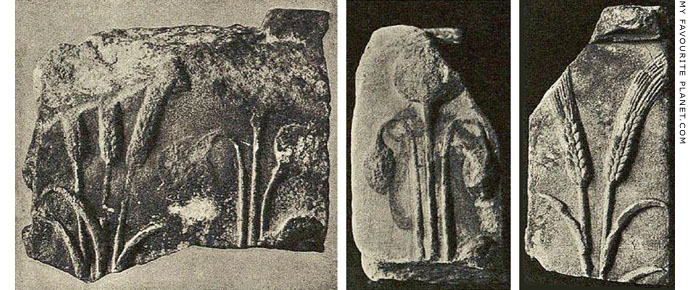

The triglyphs of this fragment are decorated with a relief of a sheaf of wheat (left), a symbol of Demeter, and the sacred kiste, the container in which the sacred objects of the Mysteries were kept. The metope has a relief of a rosette, thought to be a stylized poppy, another symbol of Demeter. Unusually for Eleusis, the inscription is in Latin rather than Greek, due to the gateway's dedication by Appius Claudius Pulcher, who was Consul in Rome in 54 BC. Pulcher died before the propylaia was built, and it was completed by his nephews Claudius Pulcher and Marcius Rex.

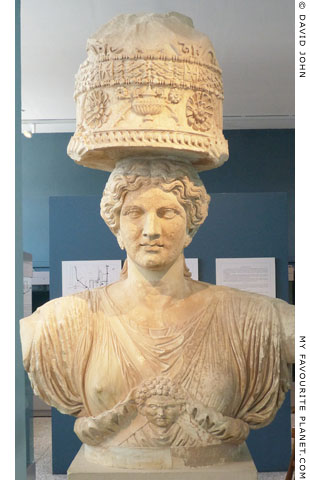

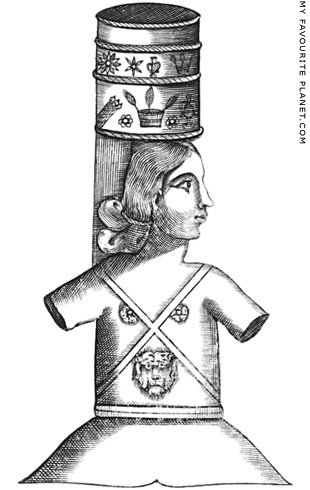

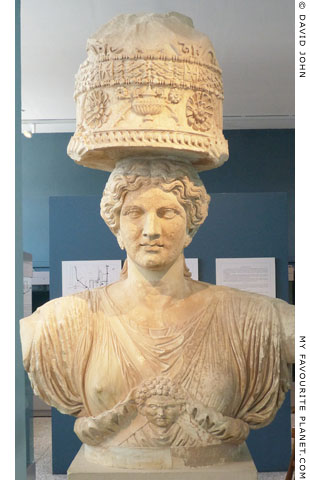

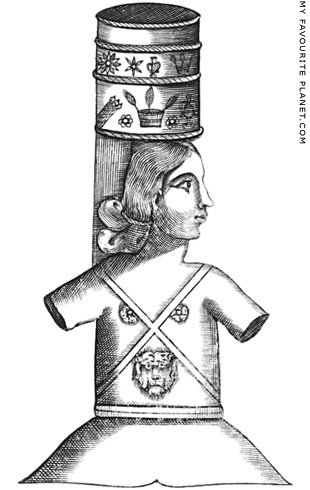

The roof on the inner facade, on the side facing the Telesterion, was supported by two kistephoros caryatids. Each of the sculpted female figures wears crossed bands around the shoulders, supporting a Gorgoneion (head of the Gorgon Medusa) between the breasts. On each head is a cylindrical kiste decorated with reliefs of a kernos, ears of corn, poppies and rosettes.

One of the caryatids is now in the Eleusis Archaeological Museum (see photo, right). The other, not so well preserved caryatid was seen by early northern European travellers to Greece in the 17th and 18th centuries, who believed it to part of a statue of Demeter or Persephone. It was removed from Eleusis by Edward Daniel Clarke in 1801, and is now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, Inv. No. GR.1.1865 [7].

See the marble bust of Marcus Arelius from the pediment of the Greater Propylaia on the Medusa page. |

|

A caryatid (or kistephoros) from the

facade of the Lesser Propylaia.

Pentelic Marble. Circa 50 BC.

Height 196 cm, width 150 cm.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 5104. |

|

| |

Marble votive statue of a piglet from the sanctuary at Eleusis.

Roman period. Pentelic marble. Length 40 cm.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 5053. |

| |

Each initiate to the cult of Demeter (μὐστης, mystis; plural, μὐσται, mystai) was obliged to sacrifice a small pig at the beginning of the celebration of the Greater Mysteries (Μεγάλα Ελευσίνια, Megala Elefsinia). In the early morning of the second day all participants, who were still in Athens after the celebration of the Lesser Mysteries (Μικρά Ελευσίνια, Mikra Elefsinia), would shout, "To the sea, o Mystai!" and travel to the seaside (perhaps Phaleron or Piraeus) to cleanse themselves and their pig in the sea as part of the purification process. After bathing each had to sacrifice their own pig, probably after they had returned to Athens.

See also a figurine of a pig from the Pella Thesmaphorion below.

Pausanias related a strange custom concerning piglets in the megara of the sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone at Potniae, near Thebes:

"Across the Asopus, about ten stades distant from the city, are the ruins of Potniae, in which is a grove of Demeter and the Maid. The images at the river that flows past Potniae ... they name the goddesses. At an appointed time they perform their accustomed ritual, one part of which is to let loose young pigs into what are called 'the halls' (megara). At the same time next year these pigs appear, they say, in Dodona. This story others can believe if they wish."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 8, section 1. At Perseus Digital Library.

According to the Roman mythographer Hyginus, the first sacrifice of a pig to Demeter was made by Triptolomos, who he also credited with establishing the Thesmophoria (see part 2):

"Ceres showed how to tame oxen, and taught her foster-son Triptolemus [to sow grain]. When he had sown it, and a pig rooted up what he had planted, he seized the pig, took it to the altar of Ceres, and putting grain on its head, sacrificed it to Ceres. From this came the custom of putting salted meal on the victim."

Hyginus, Fabulae, sections 200-277, section 277, First inventions. At the Theoi Project.

For further information about Hyginus, see the note in Homer part 2. |

|

An Athenian coin with Eleusinian symbols.

On this side a pig, tghe sacred animal of

the Eleusinian Mysteries. On the other

side Triptolemos, the mythical king of

Eleusis, in his flying chariot (see part 2).

4th century BC.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

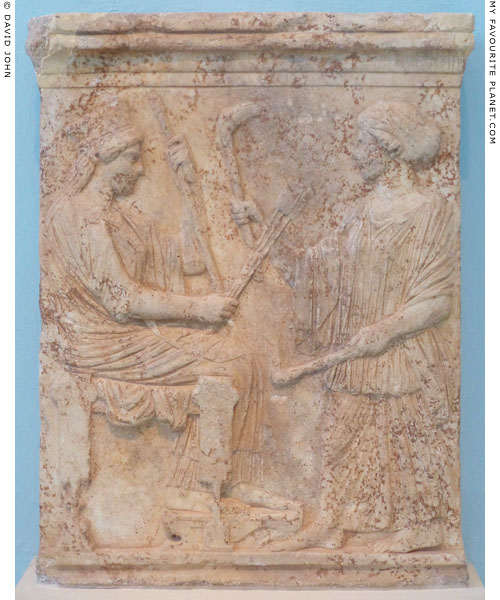

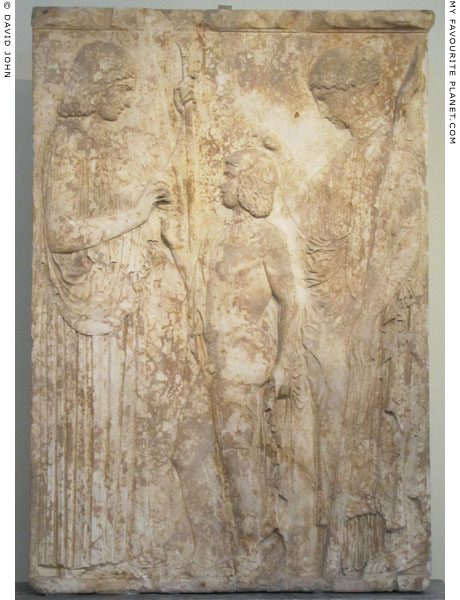

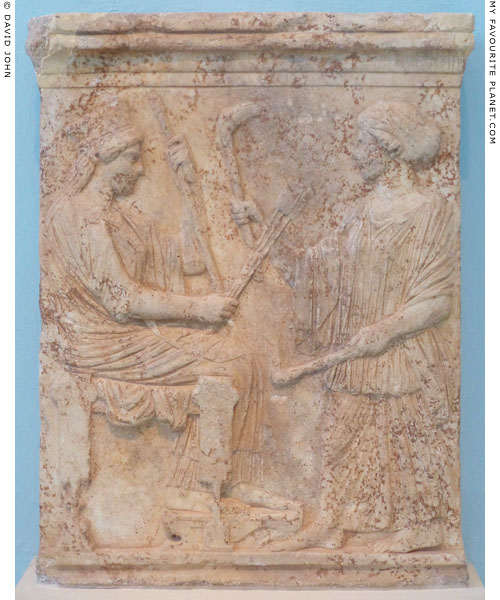

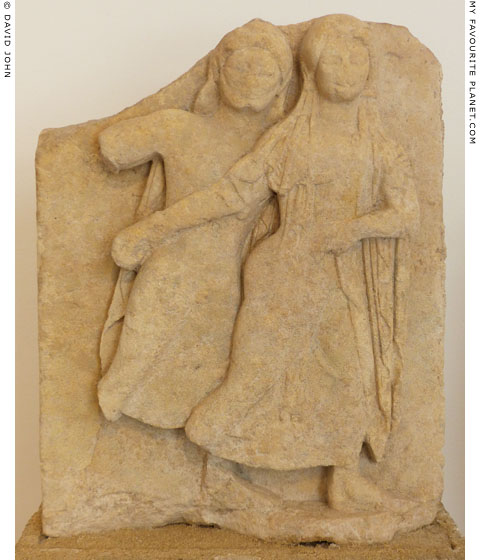

Marble votive relief depicting Demeter enthroned, and Persephone (Kore)

or Hekate standing with two torches, one raised and the other lowered.

From Eleusis. First quarter of the 5th century BC.

Height 78 cm, width 56 cm, thickness 9-12 cm.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 5085.

|

| This is the oldest surviving sculptural representation of Demeter from Eleusis. According to George Mylonas [see note 6] and others, the figure on the right may be Hekate, or even a priestess, rather than Persephone. There are several variations on the myth of Demeter and Persephone. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Hekate assists Demeter in her search for Persephone who has been abducted by Hades, and later becomes Persephone's attendant in the Underworld. |

|

|

| |

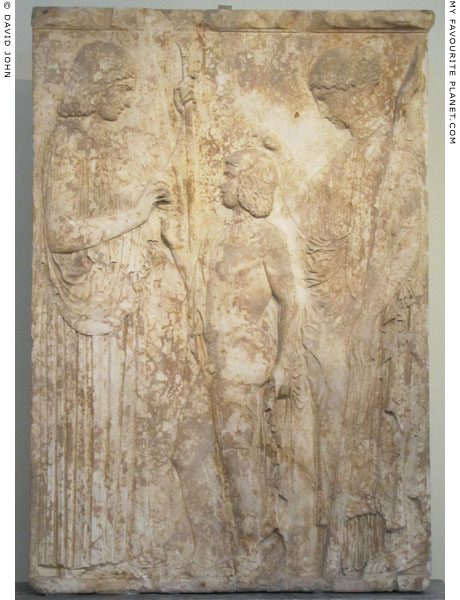

"The Great Eleusinian Relief", a marble stele from Eleusis with

a votive relief showing Demeter, Triptolemos and Persephone.

Pentelic marble, circa 440-430 BC. Found in Eleusis in 1859.

Height 218 cm, width 152 cm, depth 21.5 cm, depth of relief 3 cm.

The figures are slightly over life-size.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 126.

|

The discovery of the stele was a chance find. It had been reused as a paving stone on the floor of the Church of Saint Zacharias (Άγιος Ζαχαρίας), outside the sanctuary. [8]

This relief is thought to depict a scene central to the cult of Demeter and Persephone, the myth of how Demeter (left, holding a sceptre) gave ears of wheat to the young Triptolemos (Τριπτόλεμος, threefold warrior), son of the Eleusinian King Keleos, as the gift of agriculture to mankind (see note 11 and photos in Part 2). However, it has also been suggested that the boy may be Iakchos, Ploutos, Demophon, Eumolpos, Initiate from Hearth, Nisos or even an ordinary initiate. The wheat and the goddess's crown are not visible on the relief and were probably attachments or painting. Demeter's daughter Persephone, standing to the right with a torch, blesses the boy by placing her right hand over his head.

Pausanias wrote that there was a temple of Triptolemos at the entrance to the sanctuary at Eleusis.

"The Eleusinians have a temple of Triptolemus, of Artemis of the Portal, and of Poseidon Father, and a well called Kallichoros (Lovely dance), where first the women of the Eleusinians danced and sang in praise of the goddess. They say that the plain called Rharium was the first to be sown and the first to grow crops, and for this reason it is the custom to use sacrificial barley and to make cakes for the sacrifices from its produce. Here there is shown a threshing-floor called that of Triptolemus and an altar."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 38, section 6. At Perseus Digital Library.

The Kallichoros well is to the left of the entrance to the sanctuary. The location of the plain of Rharium (or Rarian meadow) is unknown. For further information about the cakes used in the cult of Demeter and Persephone see Corinth and Isthmia, Pella and Delos below. |

|

|

| |

Fragment of a marble votive relief depicting Demeter disguised as an old woman, facing left,

sitting on the "Mirthless Stone" (ot "Mirthless Rock"; Αγέλαστος Πέτρα, Agelastos Petra,

literally smile-less stone or stone without laughter) on which she rested during her search

for Persephone. She is approached from the left by five worshippers, conventionally depicted as

a smaller scale: three men, a woman and a girl, perhaps a slave, carrying a basket on her head.

From Eleusis. Around 330-320 BC. Length 46 cm.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 5066. |

| |

The upper part of the "Rheitoi Decree" stele, an inscribed marble stele with a decree

concerning the building of a bridge over the Rhetoi Lake (Λίμνη Ῥειτοὶ, today called

Lake Koumoundourou, Λίμνη Κουμουνδούρου), actually a lagoon next to the sea, on

the marshy Thrasian Plain near Eleusis. The 1.5 metre wide bridge was part of the

Sacred Way (Iera Odos) between Athens and Eleusis.

The relief at the top of the stele shows four female figures, from left to right:

Demeter, Persephone and the personification of the Demos of Eleusis clasping

hands with Athena, personifying Athens.

421-420 BC. Found in fortification wall near Greater Propylaia of Eleusis in 1887.

Present height of stele 90 cm, width 53 cm.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 5093. Inscription IG I³ 79.

|

| The relief depicts four figures standing side by side, three females and a male. All the female figures wear peploi. On the far right of the relief Athena, wearing a crested Attic helmet and holding a spear, is shown frontally with her head turned to the left to face a young man wrapped in a himation, depicted as slightly smaller and in profile, thought to be either the personification of the Demos of Eleusis or a local hero, perhaps Triptolemos. On the left Demeter and Persephone are shown frontally. Demeter lifts the edge of her peplos over her left shoulder (as in another relief from Eleusis, see Part 2). Persephone holds two torches, that in her left hand is raised, while the one in her right hand is lowered, mirroring the pose of the figure in the relief above. |

|

|

|

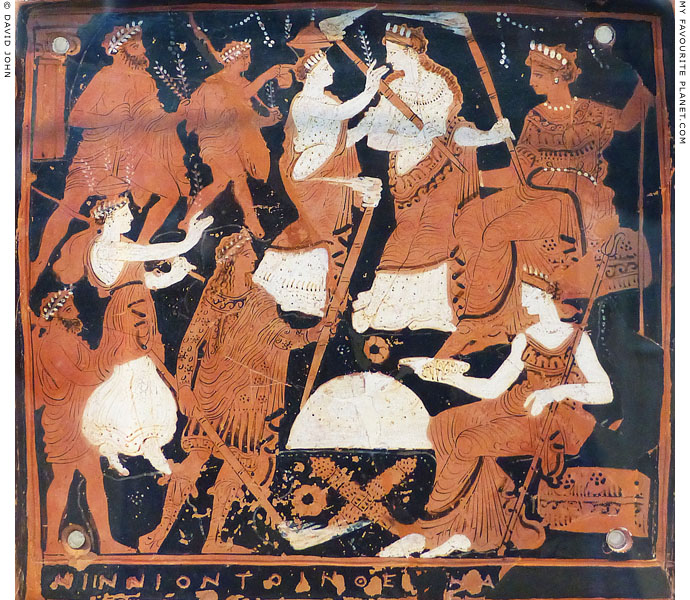

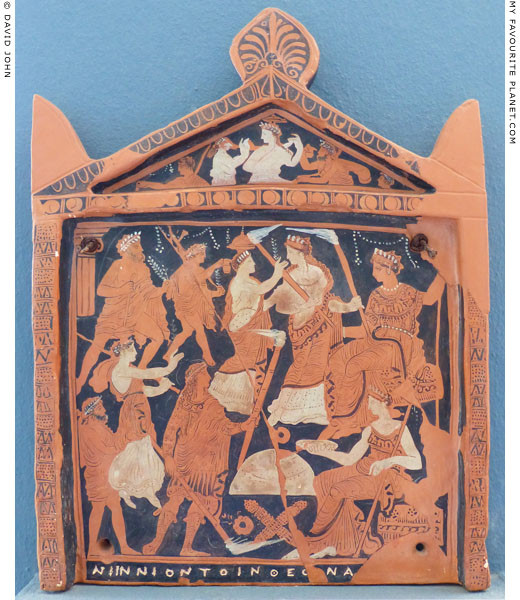

The "Ninnion Tablet", a terracotta votive pinax (painted plaque) [9], dedicated by a

woman named Ninnion to Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis. The pinax, in the form

of a naiskos (ναΐσκος, small temple), depicts the religious rites of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Made in Attica, dated to around 370 BC. Found in Eleusis in 1895.

Height 44.5 cm, width 33 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inv. No. 11036.

|

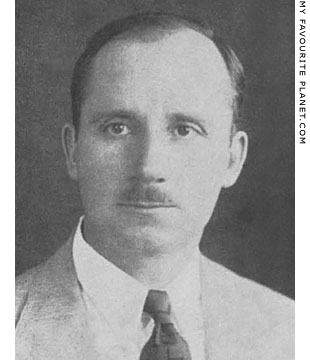

The "Ninnion Tablet" was found in nine fragments, to the south of the Telesterion at Eleusis, during excavations directed by the Greek archaeologist Andreas Skias (Ανδρέας Σκιάς, 1861-1922). The four holes in the pinax indicate that it was hung on a wall, perhaps at the Telesterion itself.

The inscription on the base states that the pinax was dedicated by a woman named Ninnion to the "two goddesses": ΝΙΝΝΙΟΝ ΤΟΙΝ ΘΕ[ΟΙ]Ν Α[ΝΕΘΗΚΕN] (NINNION TOIN THEOIN ANETHIKEN). It was scratched on the ceramic surface after it had been fired, and it has been suggested that the pinax was sold ready-made and then dedicated by the purchaser.

It is generally agreed by scholars that the pinax is unique in depicting one or more rituals of the secret Eleusinian Mysteries (Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια). However, the very secrecy surrounding the Mysteries and the puzzling iconographies of surviving ancient artworks associated with them have so far made an entirely convincing interpretation of the persons, objects, symbols and activities painted on the plaque impossible. There have been several attempts to decipher exactly who and what is represented, whether the main scene depicts one ritual or two separate phases of the rites, or whether the action takes place at the Lesser or Greater festival. [note 6]

Below is an attempt to describe the paintings on the pinax, roughly following the museum labelling, with caveats, probablys and maybes. |

|

|

| |

Detail of the pediment (gable) of the naiskos on the "Ninnion Tablet".

|

The pediment of the naiskos is topped by an akroterion in the form of an ancathus leaf.

The painting on the pediment may depict participants at the pannychis, the sacred all-night feast. The central figure, perhaps a deity, priestess or initiate, wearing a wreath and with a kernos (a sacred vessel) fastened to his/her head, is surrounded by four figures, also wreathed. The two outside figures are youths; the female figure left of the central figure appears to be playing pipes (the surface is too damaged to be certain); the bearded male figure to the right holds a jug or cup.

The central figure is too indistinct to make a certain identification, and the depiction of the faces of the figures in the main scene (see below) too similar to make a comparison. White has been used for all the female figures on the pinax, except Demeter, whereas all the males are completely red. The facial features, hairstyle and garment (white with a pattern of black dots) of this figure are very similar to those of the female torch-bearer in the main scene. It is, then, most likely a female (Persephone or Hekate?), although it has been suggested that it could be Dionysus, who was associated with the Mysteries. The archaeologist George E. Mylonas [note 6] was of the opinion that Dionysus does not appear on the pinax.

Below this is a row of what appear to be lunar discs and crescents in various positions. It is not known whether these have an astronomical significance, but they may be related to the myth of Demeter and Persephone or the rites and festivals. |

|

|

| |

The main scene of the "Ninnion Tablet".

|

The main scene appears to depict the arrival of initiates at the sacred rites, and their meeting with Demeter and other deities.

The figures are arranged in two rows. At the top right Demeter, holding a staff in her left hand and seated on the "cista mystica", the secret chest (kiste) which contained the sacred objects of the Mysteries. According to another interpretation she is sitting on the "Mirthless Stone" (see above). Left of her stands Persephone, holding two torches, and below her Iakchos (Ἴακχος) the torch-bearer, receive a procession of men and women initiates arriving at the sanctuary, all crowned with myrtle wreaths and holding blossoming branches and staffs. Each woman has a kernos, a sacred vessel (see photos below), fastened to her head.

In the centre of the lower row are the wreathed omphalos above intersecting bakchoi (a bakchos was a mystic myrtle staff), symbols of the mystery rites. The seated female figure at the bottom right may be a deity, a priestess of Demeter or Ninnion herself.

Alternatively, The female figure with the torches to the left of Demeter may be the goddess Hekate, and the seated figure below may be Persephone. |

|

|

| |

A modern copy of the "Ninnion Tablet" in the museum at Eleusis.

The replica was commissioned by the Greek Ministry of Culture,

and made in 2009 by Thomas Kotsigiannis.

Another replica of the pinax was made by the Swiss artist

Émile Gilliéron (1850–1924) shortly after its discovery.

The copy has the advantage of not being displayed behind glass,

and therefore it is easier to look at without reflections or shadows.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Fragment of a statue base with a relief showing Eleusinian initiates in

a procession, each carrying a bakchos (βάκχος), the mystic myrtle staff.

Pentelic marble. Roman period, around 150 AD, during the reign

of Antinonus Pius (138-161 AD). Height 124 cm, width 95 cm.

Outside the Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. E 1143.

|

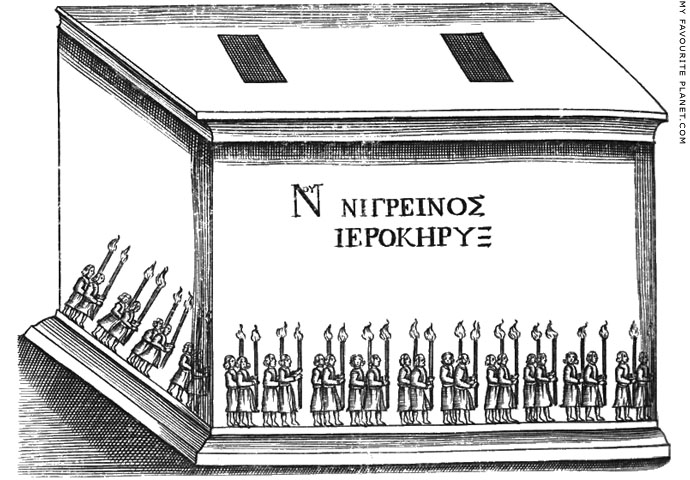

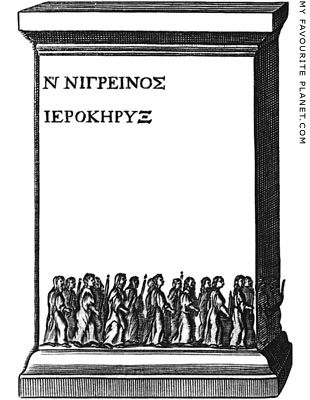

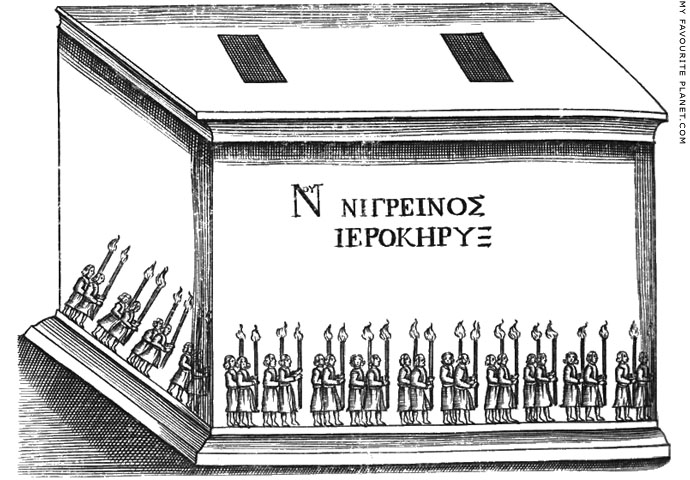

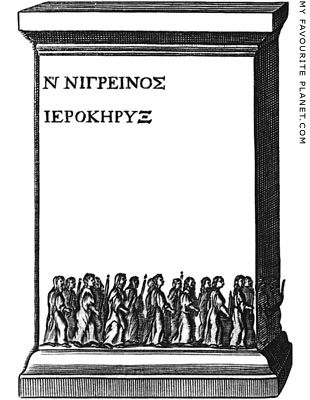

This is one of two fragments of the statue base displayed unlabelled in the courtyard of the Eleusis museum. The base is believed to have supported a now lost bronze portrait statue of Lucius Nummius Nigreinos from the Attic deme of Gargettos (Γαργηττός), who served as a sacred herald (ἱεροκῆρυξ, hierokerys) in the Eleusinian Mysteries, probably erected in the sanctuary shortly after his death.

It was decorated on three sides by similar low reliefs of male and female bakchos-bearing initiates of the Eleusinian mysteries. The reliefs may represent the Great Procession of intitiates from Athens to Eleusis led by priests and cult officials. It has also been argued that they are repetitions of a single scene rather than a continuous tableau, and that Nummius Nigreinos himself appears on all three. The best preserved relief, in the photo above, may show him in the centre of the front row.

The subject of the statue was identified by the dedicatory inscription at the top of the base, which is now broken off and lost, but which was copied by both Jacob Spon and George Wheler in 1676 (see drawing below).

Νού[μμιος] Νιγρεῖνος ἱεροκῆρυξ

Noummius Nigreinos, sacred herald

Inscription IG II² 3574 (I.Eleusis 462).

From George Wheler, A journey into Greece, pages 428-429. London, 1682.

See: Iphigeneia Leventi, The relief statue base of Nummius Nigreinos, sacred herald of the Eleusinian mysteries. The iconography of Eleusinian cult initiates and officials in Roman Imperial times. In: Cristina-Georgeta Alexandrescu (editor), Cult and votive monuments in the Roman provinces. Proceedings of the 13th International Colloquium on Roman Provincial Art, 2013, pages 63-72. Mega Publishing House, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2015. At academia.edu.

The illustrated article discusses the reliefs, also with reference to the "Ninnion Tablet" (see above) and the hierophant relief from the Olympieion in Athens (see below). Includes a bibliography. |

|

|

| |

A drawing by George Wheler of what is thought to be the same statue base

in Eleusis, made in 1676, when the base was still intact and with the inscription.

|

Like other illustrations in Spon and Wheler's accounts of their journey together through Italy, Turkey and Greece, which they published separately, the drawing of the base is rough and bears little resemblance to the actual object. They believed it to be the base for the caryatid they also saw in the sanctuary, which they took for a statue of Demeter (see above).

"A little higher on the brow of the hill we found a large basis for a statue, which we judg'd to belong to that of the goddess. There was written upon it only ΝΟΥ ΝΙΓΡΕΙΝΟΣ ΙΕΡΟΚΗΡΥΞ Noumilius Nigrinos, priest; which perhaps, was the name of him that erected the statue. But that which is most remarkable about it, is a small basso-relievo, representing the Procession of Ceres, used to be made by the Athenians, in memory of her going about the world, in search of her daughter Proserpina, stollen by Pluto, after she had lighted her torches at Mount Aetna. The whole multitude carry flambeau's they call Δαδία; and to them belonged officers, whom they call'd Δαδῦχοι; being, I suppose, the chief regulators of that ceremony."

George Wheler, A journey into Greece in company of Dr Spon of Lyons, Book VI, pages 428-429, drawing on page 429. William Cademan, Robert Kettlewell, and Awnsham Churchill, London, 1682. At Googlebooks.

Another drawing of the base appeared in Spon's book (image right). Both illustrations show a relief at the bottom of the front of the base depicting pairs of people, walking to the right, each holding a lighted torch. However, Spon's base, which is taller and with the inscription in the top left corner, has seven pairs, while Wheler's has ten. The passages in both books describing the bases are almost indentical, but Spon's (in French) refers to the dedicator as "Noumenius Nigrimus" (a printing error?), "Héraut sacré des Desses" (sacred herald of the goddess).

Jacob Spon and George Wheler, Voyage d'Italie, de Dalmatie, de Grece, et du Levant, faités années 1675 et 1676, Tome II, pages 216-217, drawing on page 216. Henry & Thedore Boom, Amsterdam, 1679. At the Internet Archive. |

|

The drawing of the statue base

in Jacob Spon's book. |

|

| |

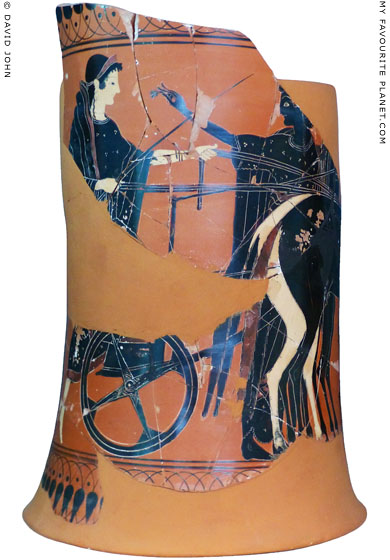

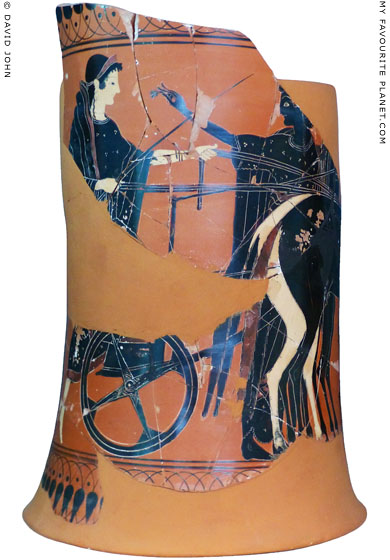

Restored fragments of a black-figure krater stand with a painting

of a goddess, perhaps Demeter, on a four-hourse chariot.

Apollo (?), holding a kithara, offers her a flower. At the front of

the horses (not visible in photo) stand Artemis (?) and Hermes.

Found in Pyre B', the Telesterion, Eleusis. Made in the workshop

of the Madrid Fountain Painter, around 520-510 BC.

The other side shows Artemis (?) and Hermes.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 468. |

| |

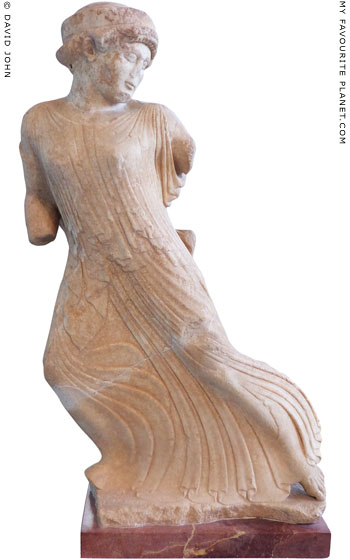

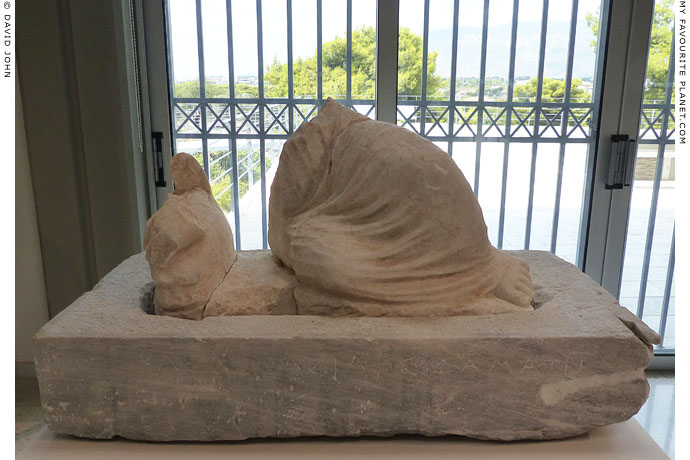

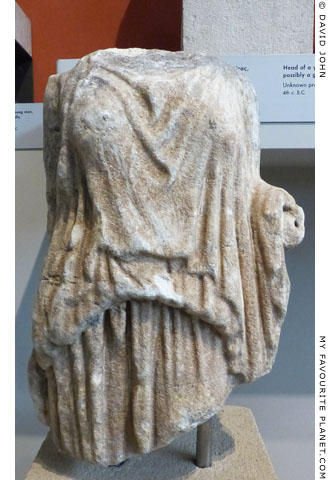

Statue of a fleeing maiden from the pediment

of the Sacred House in Eleusis. 490-480 BC.

Height 64.5 cm.

The relief on the pediment depicted the

abduction of Persephone, and this figure may

represent one of the daughters of Okeanos.

Eleusis Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 5235. |

|

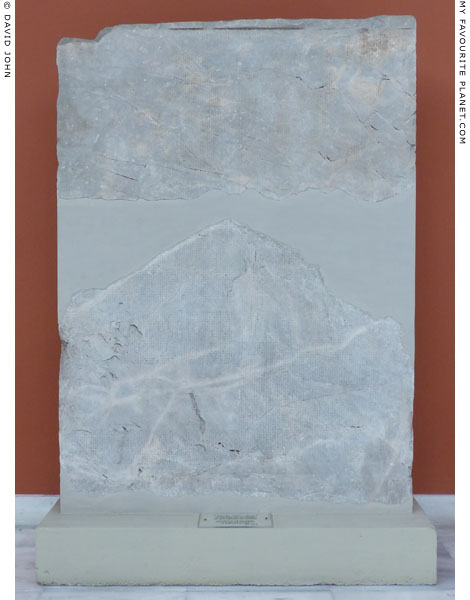

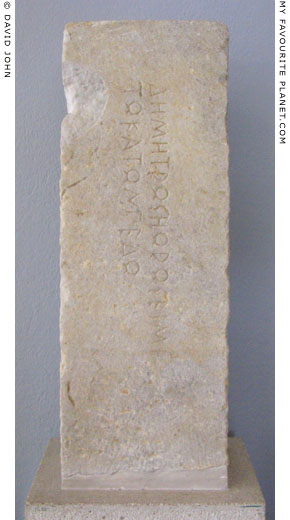

Marble stele inscribed with an Athenian

decree concerning the Eleusinian first

fruits of the harvest (ἀπαρχαί, aparchai)

for Demeter and Kore. [10]

From Eleusis. Circa 422 BC.

Height 133 cm, width 50 cm, depth 9.5 cm.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. EM 10050. Inscription IG I³ 78. |

|

| |

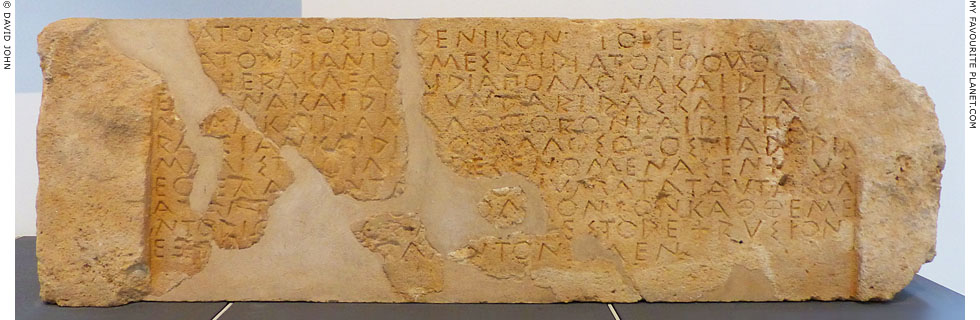

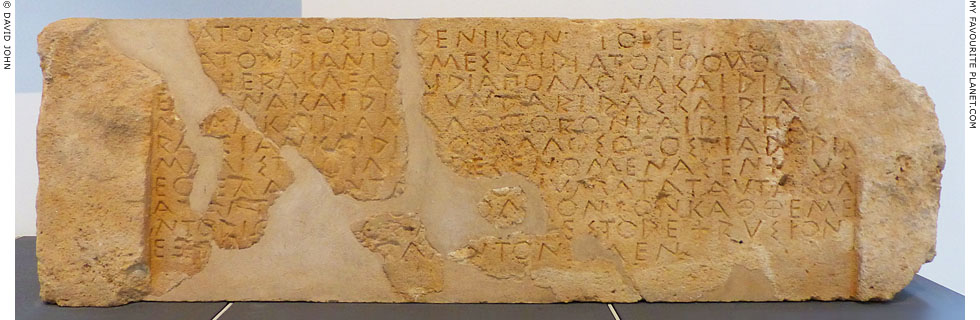

Fragmentary marble stele inscribed with the accounts of the Eleusinian

Epistatai and the treasures of Demeter and Kore. 329/328 BC.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. Nos. EM 10048 + 10051.

Inscription IG II² 1672. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

| |

| |

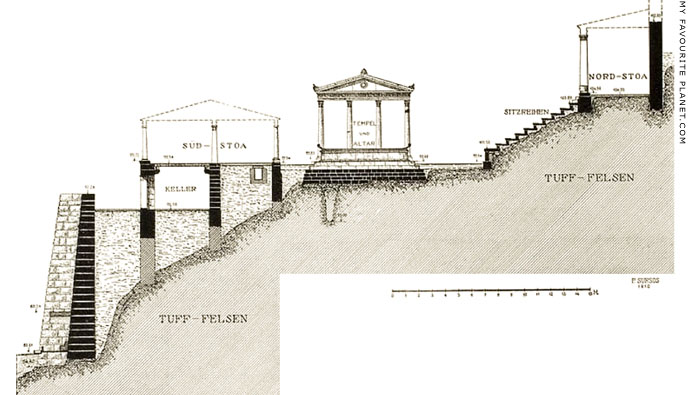

Plan of the Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis.

Source: Gustave Fougères, Grèce I: Athènes et ses environs.

Guides Joanne, Libraire Hachette, Paris, 1906. |

| |

| |

Sanctuaries of Demeter and Persephone

Athens |

|

|

| |

The site of the sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone in Athens,

known as the City Eleusinion (Ελευσίνιον), on the east (left) side

of the Sacred Way, between the Agora and the Acropolis. |

| |

The main sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone in Athens was known as the City Eleusinion (Ελευσίνιον), in which the sacred cult objects (ἄρρητα ἱερά, arreta hiera) were kept during the first four days of the celebration of the Greater Mysteries, before the participants made their way to Eleusis. Located to the southeast of the Athenian Agora, along the Sacred Way up to the Acropolis, the sanctuary contained a temple of Demeter and Persephone and a temple of Triptolemos. [11]

There was also a temple of Demeter near the gates to the city at Kerameikos, northwest of the Agora, which contained statues of Demeter, Persephone and Iakchos by Praxiteles [note 11]. Another sanctuary for the Eleusinian Mysteries stood near the River Ilissos, to the south of the Acropolis (see below).

An inscribed horos (boundary stone) of the 4th century BC, found in the the Athenian Agora, marked the sanctuary of Demeter Azesia (----- ΙΕΡΟΥ ΔΗΜΗΤΡΟΣ ΑΞΗΣΙΑ), who is also known from a fragment of Sophokles. The location of the sanctuary is unknown. [12]

See a statuette of Demeter sitting on the sacred kiste found in the Agora in part 2. |

|

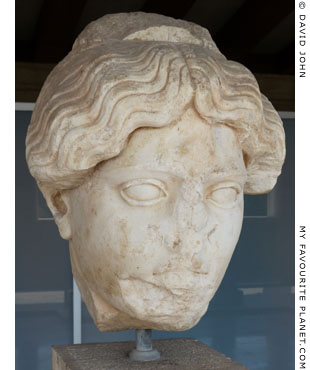

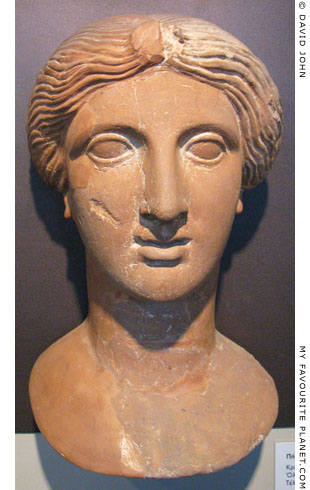

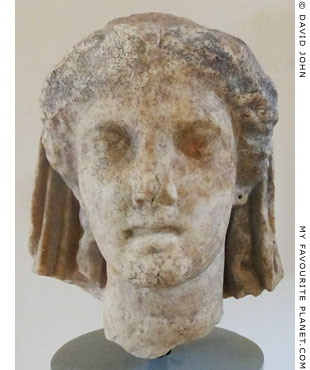

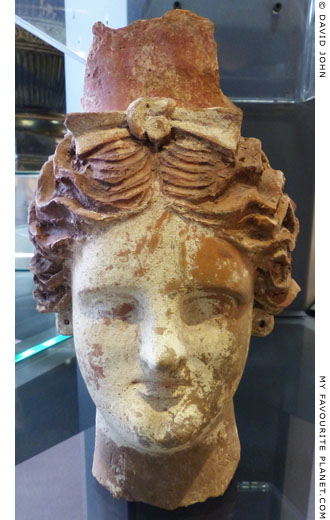

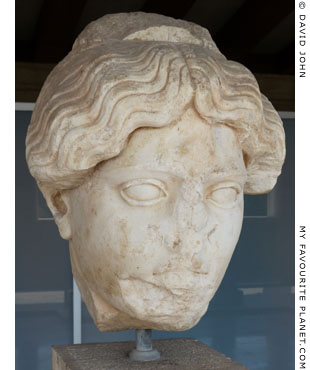

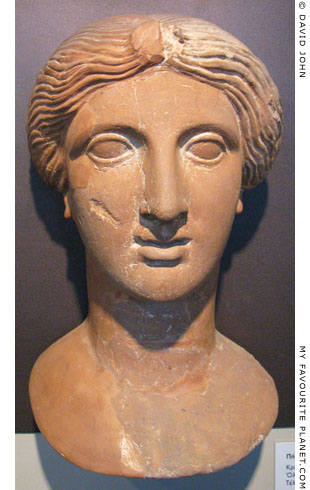

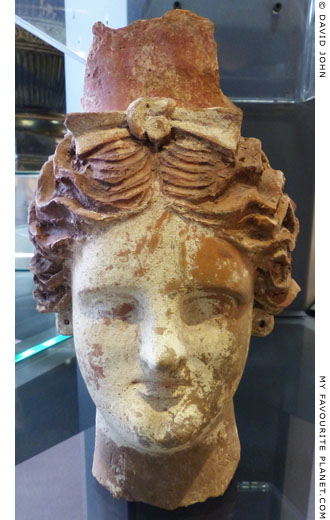

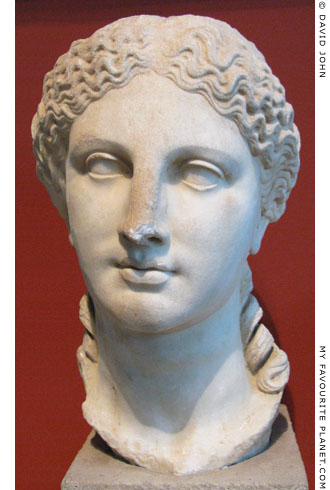

Marble head of a goddess,

probably Persephone.

From the Athens Agora. 2nd century AD,

copy of an early Classical work.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 547. |

|

| |

Marble votive relief of Demeter, Kore, Iakchos and worshippers, from the City Eleusinion, Athens.

Late 4th century BC. Found 11 June 1947 at the west foot of the Areopagus.

Pentelic marble. Height 21.8 cm, width 31.2 cm.

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. S 1251.

|

| Demeter, enthroned left, holds out a phiale (φιάλη, libation bowl; Latin, patera) in her right hand, and a staff in her left. Right of her stand Persephone, holding a long torch diagonally, and Iakchos (Ἴακχος: Latin, Iacchus), carrying the infant Ploutos (Wealth) who holds a cornucopia. On the right are three smaller worshippers, a woman, a man and a child, probably the dedicators of the relief. The detailing of the low relief is much finer than can be seen under the flat lighting in the museum. |

|

|

| |

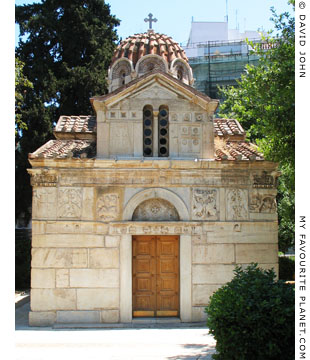

Part of an ancient frieze above the south door of the Byzantine "Little Metropolis"

church in central Athens, thought to be from the City Eleusinion.

|

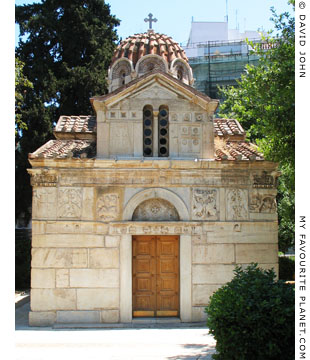

The small Byzantine church of Panagia Gorgoepikoos (Παναγία Γοργοϋπήκοος, the swift-hearing Virgin), also known as the Little Metropolis (Μικρή Μητρόπολη, Mikri Mitropoli), and for a short while renamed as the church of Agios Eleutherios (Άγιος Ελευθέριος), acted as the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens during the Turkish occupation, until the much larger modern cathedral was built next to it 1842-1862.

It is not known when the church was built, perhaps as early as the 9th century or as late as the 15th century. It was constructed using marble spolia, material from various older pagan and Christian buildings, and also contained ancient inscriptions and a Roman period sundial, which is now in the British Museum (see Athens Acropolis gallery page 36). Attempts have been made to identify the parts of ancient reliefs built into the walls of the church.

This Doric frieze, above the south door, is part an entablature, with triglyphs and metopes decorated with the following motifs in relief (left to right): two crossed myrtle torches and three poppies; a phiale (libation bowl); a plemochoe (see below); a boukranion (ox skull) with a fillet. All these symbols are also found on building decorations at the Sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis. It is thought that the frieze is from the City Eleusinion, south of the Athenian Agora, probably from the Hellenistic propylon (monumental gateway), built in the 2nd century BC on the west side of the sanctuary, facing the Sacred Way to the Acropolis (see photo on Athens Acropolis gallery page 1).

See:

Monica Haysom, Time and religion in Hellenistic Athens: An interpretation of the Little Metropolis frieze. PhD thesis, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University, 2015.

Bente Kiilerich, Making sense of the spolia in the Little Metropolis in Athens. In: Estratto dalla rivista Arte Medievale, nuova serie anno IV (2005), 2, pages 95-114.

The marble lintel above the frieze is decorated with reliefs of three elaborate crucifixes, each in a different style.

The plemochoe (πλημοχόη), a vessel also known as a little kotulos, shaped like a spinning top, was particularly associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries. According to the Greek rhetorician Athenaeus of Naucratis (Ἀθήναιος Nαυκρατίτης, 2nd - 3rd century AD), two plemochoai were used in the rituals of the Greater Mysteries at Eleusis and gave their name to the last day of the celebrations there.

"There is the plemochoe, too. This is an earthenware vessel, shaped like a top, not very steady; and some people call it the cotyliscus, as Pamphilus tells us. But they use it at Eleusis on the last day of the Mysteries, which day they call Plemochoai, from the cups. And on this day they fill two plemochoae, and place one looking towards the east, and the other looking towards the west, saying over them a mystic form of words; and the author of the Pirithous names them (whoever he was, whether Critias the tyrant, or Euripides), saying:

That with well-omen'd words we now may pour

These plemochoae into the gulf below."

Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists, Book 11, chapter 93. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

The "Little Metropolis" church,

Mitropoleos Street, Athens. |

|

|

Inscribed facade of a statue base dedicated to Demeter and Kore and signed by Praxiteles.

Pentelic marble. Around 360-350 BC. Found in May 1936 in the Athenian Agora, north

of the Hephasteion. Height 67.2 cm, width 135 cm, width of left side 67.5 cm.

In the lower colonnade of the Stoa of Attalus,

Agora Museum, Athens. Inv. No. I 4165.

|

Two statues stood on the base: the first, by Praxiteles, depicted Kleiokrateia, daughter of Polyeuktos of Teithras (a deme of east Attica); the second portrayed her husband Spoudias of Aphidnai. The signature of the sculptor of the second statue, "(..)usicles" is incomplete. The Praxiteles signature is written in letters much smaller than the rest of the inscription, and not so deeply cut, so that it is difficult see except when lit from the side (mid-late afternoon).

[Δή]μη[τ]ρι καὶ Κόρει

[Σπο]υ[δίας]

— — — —

[Ἀφι]δ[ναῖος].

vacat

—υ̣σ[ι]κλ̣[ῆς ἐποίησεν].

vacat

Κλειοκράτεια

Πολυεύκτου

Τειθρασίου

θυγάτηρ

Σπουδίου γυνή.

Πραξιτέλης ἐποίησεν.

Inscription SEG 17:83.

It is thought that the statues were originally set up in the City Eleusinion. The base probably had a poros limestone core faced with marble slabs, parts of which were found reused in a 1st century BC wall, between the Hephaisteion and the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherius, and on a wall of a modern canal.

In the late 360s Demosthenes wrote an oration (Oration No. 41) against Spoudias, who was in dispute with Kleiokrateia's family over the repayment of a loan. It has been suggested that the couple were at this time in financial difficulties, and thus may have commissioned the statues at an earlier date when they had been better off. [13] |

|

| |

Terracotta figurine of an enthroned

goddess, possibly Demeter or Hera.

Made in Athens, around 500 BC.

British Museum.

Inv. No. GR 1966.3-28.19. |

|

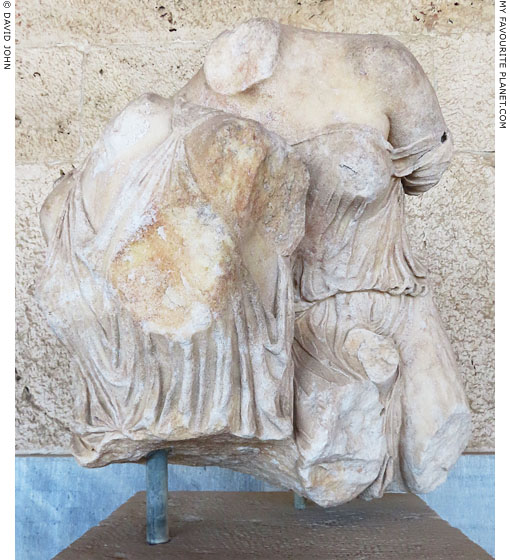

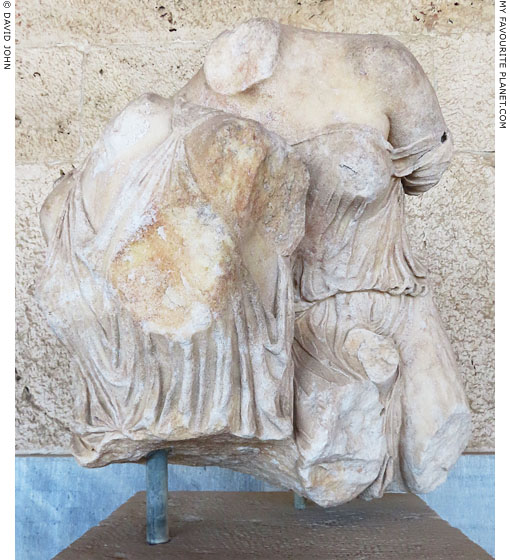

Part of a marble relief of Demeter

and Persephone from the Athenian

Acropolis. Late 5th century BC.

Acropolis Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. Acr. 1348. |

|

| |

Marble votive relief dedicated by an association of Attic launderers,

men and women who washed clothes at the Ilissos river, Athens.

Around 350-340 BC. Found in 1759 at the Panathenaic Stadium, Athens.

Pentelic marble. Height 40.5 cm, width 44 cm, depth 9 cm.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. Sk 709.

Acquired by Gustav Friedrich Waagen in 1841 from the Museum Nani, Venice. |

| |

The findspot of the Panathenaic Stadium suggests that the relief came from a sanctuary on the nearby Ilissos river, where there was a sanctuary of Pan, Hermes and the Nymphs, a sanctuary for the Eleusinian Mysteries, and the Temple of Artemis Agrotera (Artemis of the Fields).

The front of the marble slab is divided vertically into three areas, with a relief above and below the dedicatory inscription. The relief was dedicated to "the nymphs and all gods" by twelve male and female launderers (10 washermen and 2 washerwomen) whose names are thought to be those of slaves.

οἱ πλυνῆς Νύμφαις εὐξάμενοι ἀνέθεσαν καὶ θεοῖς πᾶσιν

Ζωαγόρας [Ζ]ωκύπρου, Ζώκυπρος Ζωαγόρου, Θάλλος, Λεύκη

Σωκράτης Πολυκράτους, Ἀπολλοφάνης Εὐπορίωνος, Σωσίστρατος,

Μάνης, Μυρρίνη, Σωσίας, Σωσιγένης, Μίδας.

Inscription IG II² 2934.

The scene above the inscription is set in a cave and shows Hermes leading a procession of three Nymphs towards a mask of the river god Acheloos on the far left. On the right Pan sits cross-legged playing his syrinx (pan pipes).

On the right of the lower scene a seated goddess, either Demeter or Artemis, is attended by a standing deity, either Persephone (Kore) or Hekate, holding a long torch. On the left a bearded male figure, depicted at the same scale as the goddesses, stands before an altar with a horse. He is perhaps a local hero or patron of the launderers. It has been suggested that he may be Demophon (Δημοφῶν), son of King Keleos and Queen Metaneira of Eleusis. He wears a short chiton (tunic) and a chlamys (short riding cloak) and holds in his right hand an object which is now broken and unidentifiable. |

|

Part of a marble votive relief found in

the area of Byronos-Pangrati, Athens,

to the south of the Ilissos River. Demeter

stands behind seated Persephone. Part

of an inscription with Demeter's name is

preserved on the anta of the relief.

Around 420 BC.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 3572. |

|

| |

Cast of an Athenian marble votive relief of Demeter, Persephone and a hierophant

(ἱεροφάντης, revealer of sacred things), a high priest of their cult from the Attic

deme of Hagnous, southeast of Athens. According to the inscription on the lower

edge of the frame, the hierophant, referred to only as "Hagnousios", dedicated

the relief to the goddesses of the Thesmophoria festival.

Classicizing work of the Roman Imperial period, 2nd century AD.

Found in 1959 during excavations by John Travlos north of the

Olympieion, Athens. Height 63 cm, width 67.5 cm.

In situ at the findspot, in the archaeological site of the Olympieion and Ilissos Shrines, Athens.

The original is in storage in the Agora Museum, Athens.

Third Ephorate of Antiquities, Athens Collection. Inv. No. L 13114. |

| |

| |

Sanctuaries of Demeter and Persephone

Corinth and Isthmia |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

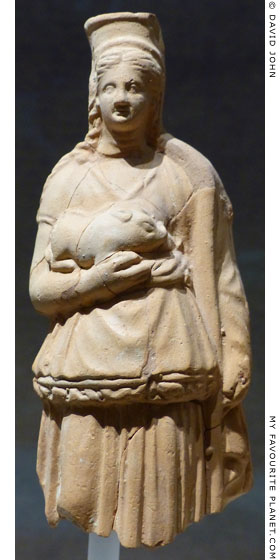

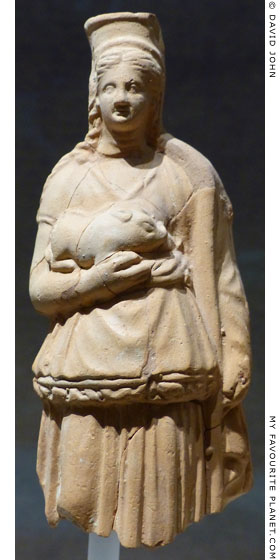

Terracotta figurines of females, each wearing a polos and holding a piglet in her

right hand. The figure on the right also holds a conical torch in her left hand.

From the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Ancient Corinth. Around 320-200 BC.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Left: Inv. No. MF-70-26 (cat. H401 *). Height 15.8 cm.

Right: Inv. No. MF-10325 (cat. H395 *). Height 10.9 cm.

|

|

The remains of the large Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Corinth (Κόρινθος) are on the north side of the steep road up from the ancient city to Acrocorinth. It was once one of the most important sanctuaries, perhaps the most important, in Corinth, and one of the largest in the Greek world. Until the late Classical period the sanctuary consisted only of a small Archaic temple (oikos, from οἶκος, a house, a dwelling), an elevated terrace with a sacrificial altar and around forty rooms for ritual dining.

In the 4th century BC a new temple was built as well as a Doric propylon (monumental gateway) and a small theatre, carved out of the rock of the slope, which seated around a hundred people. The Archaic temple was replaced by a stoa. The sanctuary was not used after the destruction of Corinth by the Roman consul Lucius Mummius Achaicus in 146 BC, but was revived in the late 1st century BC. In the 1st century AD it was redesigned and three small Ionic temples were built. One of the ritual dining areas near the propylon was converted into a Roman cult building where katadesmoi (curses, from κατάδεσμος, katadesmos, curse) were dedicated.

The sanctuary was briefly mentioned in the 2nd century AD by the Greek travel writer Pausanias, who merely noted:

"The temple of the Fates and that of Demeter and the Maid have images that are not exposed to view."

Description of Greece , Book 2, chapter 4, section 7.

It was abandoned towards the end of the 4th century AD, and from the 6th century part of the area was used as a cemetery.

As at other sanctuaries of Demeter and Persephone, thousands of votive offerings have been unearthed here, including ceramic statues, figurines, vessels and inscribed plaques, as well as terracotta models of likna (λίκνα, winnowing trays) containing cakes and breadstuffs (see photo below). The small (but fine) Corinth Archaeological Museum has space only for a few of these finds, and as at other museums, researchers have been unable to discover whether the ceramic female figures depict Demeter, Persephone, some other deity, priestesses or worshippers.

Today the area of the sanctuary is overgrown, there is not much to see there and it is not even signposted, nor is it mentioned in the glossy guidebooks to Ancient Corinth.

* Catalogue numbers of the figurines from:

Gloria S. Merker, Corinth, Volume 18, No. 4, The Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore: Terracotta figurines of the Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), 2000. At jstor.org.

A terracotta mask of Dionysus and two inscribed ceramic plaques dedicated to Dionysus were also found in the sanctuary.

See other artefacts from Corinth related to Demeter

and Persephone in Part 2: here, here and here. |

|

Terracotta female figure with

a piglet from the Sanctuary of

Demeter and Kore, Corinth.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. MF-11785 (cat. H10 *).

See photos of other

piglet-offering figures

associated with Demeter

and Persephone in part 2. |

|

| |

Terracotta votive offerings from the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Corinth.

Two model likna (λίκνα), winnowing baskets or trays used to separate the grain

from the husks after harvesting, filled with cakes and breadstuffs. Hundreds of

such votive likna were excavated at the sanctuary, where they had been

dedicated from at least the early 6th century until the 2nd century BC.

Archaic period, 6th century BC.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

See: Allaire Brumfield, Cakes in the Liknon: Votives from the Sanctuary of Demeter and

Kore on Acrocorinth. Hesperia, Volume 66, No. 1 (January - March 1997), pages 147-172.

The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA). At jstor.org.

See also terracotta figurines of a goddess holding a liknon in part 2. |

| |

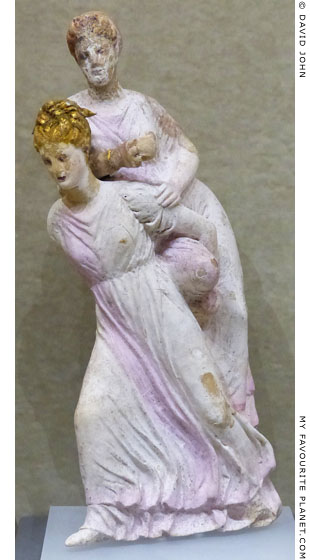

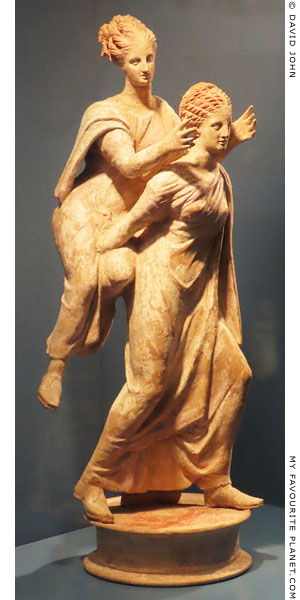

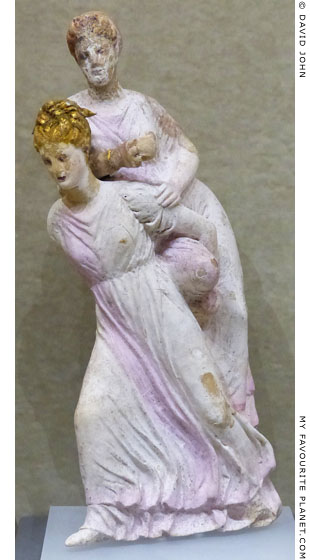

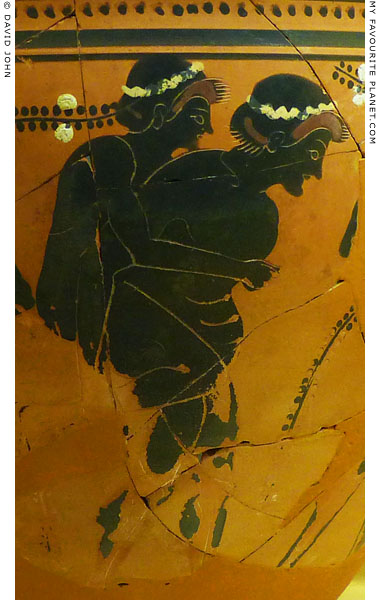

A ceramic figurine of two girls playing

ephedrismos, a piggyback game. [14]

From Ancient Corinth.

Corinth Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. MK 8250. |

|

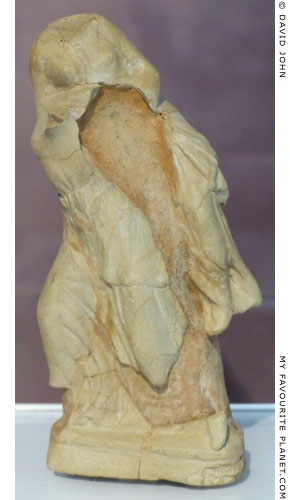

A fragmentary terracotta ephedrismos

figurine from the Rachi, Isthmia.

350-300 BC. Found among a large quantity

of ceramics in a well in the Early Hellenistic

settlement on the Rachi ridge, Isthmia,

during excavations in 1955-1956. [15]

Height 11.5 cm.

Isthmia Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. IM 955. |

|

| |

The ephedrismos (ἐφεδρισμός) figurine in the Corinth Archaeological Museum is displayed in a group of various artefacts themed "Beloved toys, favorite games" with no specific information about the individual objects or where they were found. It appears that it was either found at or associated with the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Corinth.

The fragments of a similar figurine were found in the area of the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Rachi in nearby Isthmia (see below), where the Isthmia Archaeological Museum's labelling points out that such finds were "associated with the worship of female divinities" and "similar to offerings that have been found at the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore on Acrocorinth". |

|

| |

Fragments of a marble statue of a seated child (Kleo) with

a goose on a plinth inscribed with a dedication to Demeter.

ΚΛΕΩ:ΘΑΣΙΔΟΣ:ΔΑΜΑΤΡΙ

"Kleo, daughter of Thasis, to Demeter"

A chance find in 1956 from the area of the Sanctuary of

Demeter and Kore at the Sacred Glen, Isthmia. 350-325 BC.

Isthmia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. IS 254. Inscription ΙΣ 316.

|

At Isthmia (Ισθμία), 16 kilometres east of Ancient Corinth there was another sanctuary of Demeter and Kore which is thought to have been in use from the 6th to the 4th century BC. Temples of Demeter and Kore, Dionysus and Artemis were located in the Sacred Glen (Ιερά Νάπη, Iera Nape), near the ridge known as the Rachi (Ράχη, at the modern village of Kyras Vrysi), 300 metres southwest of the Temple of Poseidon, the patron deity of Isthmia (see Niobe).

An inscribed limestone stele of the 2nd century AD lists the benefactions of P. Licinius Priscus Iuventianus, archiereus (ἀρχιερεύς, high priest for life) of the imperial cult in the Achaean League, who built and refurbished several temples and sanctuaries at Isthmia. According to the inscription, he built a peribolos (περίβολος, enclosed court, in this case a temenos or sanctuary area) with a temple of Demeter and temples of Dionysus and Artemis in the Sacred Glen (also referred to as Sacred Grove). He also provided the statues and ornaments for the temples and restored the Plutoneion (or Ploutonion). The exact dating of the stele is uncertain, but arguments have been made both for before and after the reign of Hadrian (117-138 AD). In 1676 the travellers Jacob Spon and George Wheler were at Isthmia and recorded the inscription which is now in the Museo Lapidario Maffeiano in Verona (inscription IG IV 203). [16]

The Sacred Glen was identified by the Swedish American archaeologist Oscar Broneer (1894-1992), who directed excavations at Isthmia 1959-1967 for the University of Chicago, and who discovered the Temple of Poseidon there in 1952. No remains of temple structures have yet been discovered in the glen, which may be at least partly due to the fact that the area around the Rachi had been used a quarry, and the stones of ancient buildings and monuments were reused elsewhere. However, large quantities of votive ceramics and metal objects found in the area indicate religious practice there.

The remains at the Sacred Glen site are scant, and the archaeological finds from the area of the sanctuaries, although typical of votive offerings to these deities, are not particularly exciting or enlightening, particularly compared with the treasures in the Corinth museum. However, the location, overlooking the southern end of the Corinth Canal, is evocative and the area and museum are well worth visiting. From here it is a 10 minute walk to the canal, where there are good tavernas with terraces on either side, each with a good view of the wonderful submersible road bridge and the passing ships and boats. Immediately to the south of the bridge the canal meets the Saronic Gulf with some small islands visible in the distance. To the north a pleasant footpath leads along the west side of the canal towards the motorway (over which is a footbridge), the older road bridge and the Isthmia bus station. |

|

| |

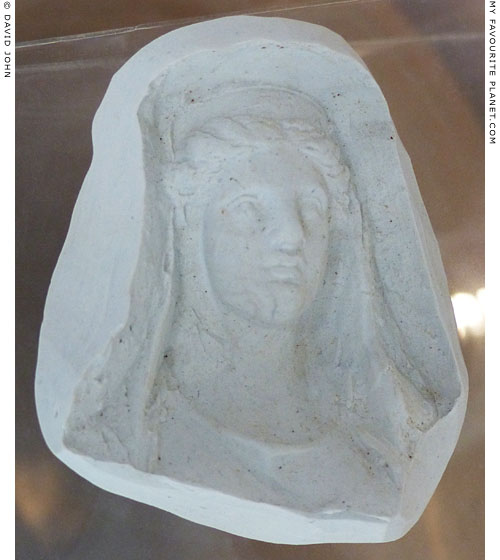

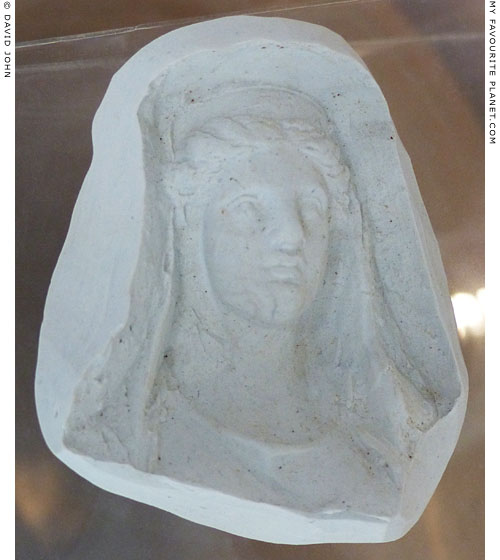

The bust of a veiled female wearing a polos, perhaps Demeter. A modern

plaster cast made from a Hellenistic mould for producing terracotta figurines.

From the area of the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Isthmia. 375-270 BC.

Isthmia Archaeological Museum. Mould, Inv. No. IM 1026. |

| |

Detail of a skyphoid krater (for mixing wine and water) with reliefs depicting a Dionysiac

scene and drunken Herakles. Inside the rim is a scratched dedicatory inscription in Doric

dialect, from Sofa to Demeter: ΣΟΦΑ ΔΑΜΑΤΡΙ (see photo below).

350-325 BC. Found in an ancient well at the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore,

in the "Sacred Glen", Rachi, Isthmia. Late 4th - early 3rd century BC.

Isthmia Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. IP 384. |

| |

The other side of the skyphoid krater from Isthmia, with two seated females (Demeter and

Persephone?) depicted in relief. The dedication to Demeter by Sofa can be seen (upside down)

inside the rim. Unfortunately, the krater is exhibited in a glass case next to a window, so that

strong multiple reflections make it difficult to see the details of the dark vessel. |

| |

| |

Sanctuaries of Demeter and Persephone

Olympia, Elis, west Peloponnese |

|

|

| |

The altar of Demeter Chamyne on the low hill north of the stadium of Olympia. 2nd century AD.

|

According to Pausanias, the epiphet of Demeter in the ancient Peloponnesian district of Elis (Ἦλις) was Chamyne (Χαμύνη), and there was a sanctuary of the goddess on the low hill north of the Olympic stadium (race track). At the time of his visit to Olympia, around 155 AD, new Pentelic marble statues of Demeter and Persephone (the Maid) in the sanctuary had been donated by the wealthy Athenian Herodes Atticus.

In 2006 the remains of what are thought to be the sanctuary of Demeter Chamyne were discovered by chance during the digging of a water supply project, around 150 metres northeast of the stadium. They include a large building, dubbed Building A, built of local limestone, oriented east-west and divided into four rooms. Dated to the early 5th century BC, it is thought to have served a cult function, and in one of the rooms was a stone feature, perhaps an altar, surrounded by votive objects.

Objects discovered during the ensuing archaeological excavations of 2007 and 2008 include 34 bronze coins of the 5th - 4th century BC, several terracotta figures, most depicting human female subjects, but also animals, particularly bovines and goats, as well as silens and masks. A number of unusual terracotta figures of Cerberus (Κέρβερος, Kerberos) of various sizes found at the site, dated to the 6th - 5th centuries BC, depict the hound of Hades with two heads on very long necks. One of the larger examples is inscribed with a dedication to Kore, Demeter (see photo right), while a smaller one depicts Kerberos with sacrificial cakes in each of its mouths (see photo below right). Part of a Roman period baths was also discovered on the site. A small selection of the finds is currently exhibited in the nearby Pyrgos Archaeological Museum. [17]

The office of cult priestess of Demeter Chamyne, appointed or "bestowed" (awarded) by the Elians "from time to time", which indicates that it was an honorary and temporary position for the duration of an Olympiad. She was the only woman allowed to attend the Olympic Games, and watched the competitions while seated on the altar of Demeter Chamyne, halfway along the length of the race course, directly opposite the stand of the competition judges (hellanodikai). "Maidens" (παρθένοι, parthenoi, virgins), girls or unmarried young women, were admitted to Olympia, and there were also games for girls, a series of foot-races known as the Heraia (Ἡραῖα, in honour of Hera; Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 16, sections 2-8).

Built of white stone blocks reused from an equestrian monument, the altar has been dated to the 2nd century AD. It has been suggested that it may have been set up for or even by financed by Aspasia Annia Regilla, the wife of Herodes Atticus, who was the priestess of Demeter Chamyne at Olympia, probably during the 233rd Olympiad in 153 AD. The couple are thought to have financed the building of the Nymphaeum of Herodes Atticus in the Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia and the connecting aqueduct around this time.

"Now the stadium is an embankment of earth, and on it is a seat for the presidents of the games. Opposite the umpires is an altar of white marble. Seated on this altar a woman looks on at the Olympic games, the priestess of Demeter Chamyne, which office the Eleans bestow from time to time on different women. Maidens are not debarred from looking on at the games."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 20, sections 8-9.

"The other side of the course is not a bank of earth but a low hill. At the foot of the hill has been built a sanctuary to Demeter surnamed Chamyne. Some are of the opinion that the name is old, signifying that here the earth gaped for the chariot of Hades and then closed up once more. Others say that Chamynus was a man of Pisa who opposed Pantaleon, the son of Omphalion and despot at Pisa, when he plotted to revolt from Elis; Pantaleon, they say, put him to death, and from his property was built the sanctuary to Demeter.

In place of the old images of the Maid and of Demeter new ones of Pentelic marble were dedicated by Herodes the Athenian."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6, chapter 21, sections 1-2.

Pausanias also reported on statues of Demeter, Persephone and Plouton in the Heraion (Sanctuary of Hera) at Olympia: chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statues of Demeter and Persephone sitting opposite each other (Book 5, chapter 17, section 3); and figures or a relief of Plouton, Dionysus, Persephone and Nymphs, one of them carrying a ball. "As to the key (Pluto holds a key), they say that what is called Hades has been locked up by Pluto, and that nobody will return back again therefrom." (Book 5, chapter 20, section 3) Another statue of Persephone, one of many dedications at Olympia of Mikythos, the 5th century BC tyrant of Rhegion (see the note in Homer part 1), stood at the side of the Temple of Zeus (Book 5, chapter 26, section 2). |

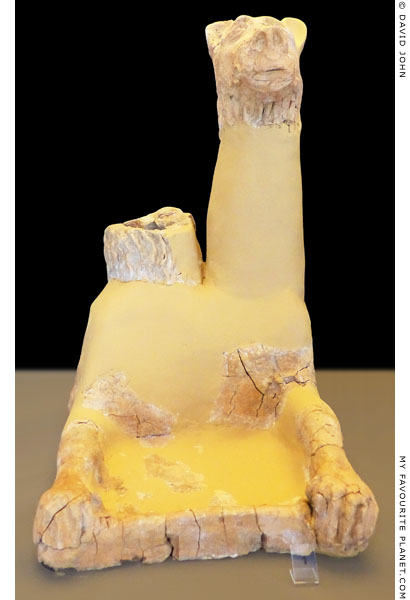

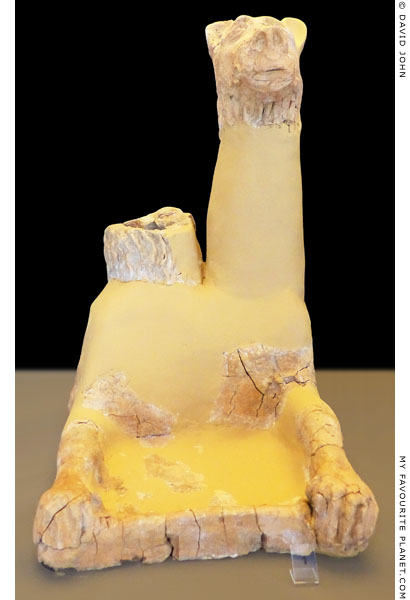

Restored fragments of a votive ceramic figurine of

two-headed Cerberus, the hound of Hades, from

the Sanctuary of Demeter Chamyne at Olympia.

On the chest are parts of an incised inscription

which is thought to have stated:

Κόρ[αι], [Δά]ματρι, [Βα]σιλεῖ

(Dedicated to) Kore (Persephone), Demeter

and Basileos (King; Plouton, king of Hades).

Late 6th century BC.

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum. |

| |

Part of a votive ceramic figurine of two-headed

Cerberus with sacrificial cakes in each of its mouths.

5th century BC. From the Sanctuary

of Demeter Chamyne at Olympia.

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

The altar of Demeter Chamyne on the northern embankment (left) of the stadium

of Olympia, around halfway along the racetrack and directly opposite the stand on

which the hellanodikai (Ἑλλανοδίκαι, competition judges) sat. Nearer the foreground

two visitors walk over the row of stones that mark the starting line of the racetrack. |

| |

A large ceramic votive figurine of a sow from

the Sanctuary of Demeter Chamyne at Olympia.

4th century BC.

Pyrgos Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

Sanctuaries of Demeter and Persephone

Macedonia and Thrace |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Two inscribed marble steles set up as horoi (boundary markers) of the sanctuary

and temple of Demeter Hekatompedos (100 feet long) in ancient Galepsos

(Γαληψός), Thrace (today Macedonia, Greece), a colony of the Thasian-Parians.

The inscriptions are written in the Parian alphabet. Around 510-490 century BC.

Δήμητρως ℎώρως εἰμὶ

τὠ κατωνπέδω

Inscription SEG 43 400.

Kavala Archaeological Museum. Invoice numbers Λ1202 and Λ1203.

|

|

Around 680 BC Greeks from Paros founded a colony on the island of Thasos, formerly a Phoenician colony. From Thasos the Parians founded or took control of several settlements on the Thracian mainland, and the new colonies became collectively known as the Thasian Peraia (ἢπειρος).

The cities included Neapolis (Kavala), Galepsos, Oisyme, Apollonia, Stryme and Krenides (later renamed Philippi), as well as smaller trading posts (ἐμπόριον, emporion; plural ἐμπορία, emporia) such as Antisara, Akontisma and Pistyros.

Pausanias reported the legend that the cult of Demeter as practiced by the Thasians was brought from Paros by a woman named Kleoboia (Κλεόβοια). She was shown as a maiden holding the cista mystica (see above) in a painting by Polygnotos of Thasos (5th century BC) that was exhibited in the Knidian Lesche, a building dedicated by the people of Knidos, at Delphi. Pausanias described the painting as depicting the mythical Underworld ferryman Charon steering his deceased passengers down the river Archeron to Hades.

"Those on board the boat are not altogether distinguished. Tellis appears as a youth in years, and Cleoboea as still a maiden, holding on her knees a chest such as they are wont to make for Demeter. All I heard about Tellis was that Archilochus the poet was his grandson, while as for Cleoboea, they say that she was the first to bring the orgies of Demeter to Thasos from Paros." [18]

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 28, section 3.

This description has been used to support the hypothesis that the Parian lyric poet Archilochos (Ἀρχίλοχος, circa 680-645 BC), who was involved in the colonization in Thrace and whose father Telesicles led the Parians to Thasos, may have belonged to a family of priests of Demeter. He was one of the first poets to use the term iamboi (as in iambic poetry), which is associated with the worship of Demeter. |

|

| |

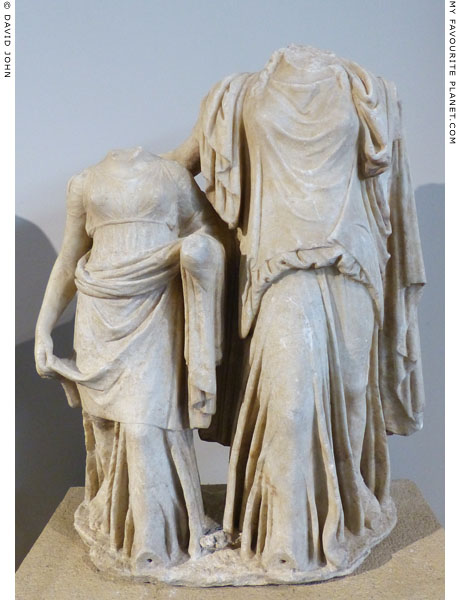

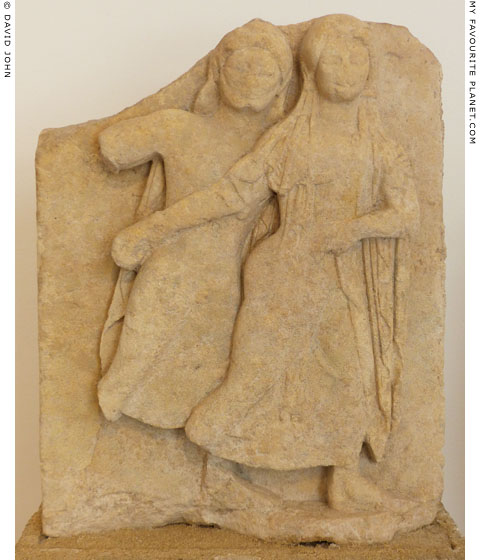

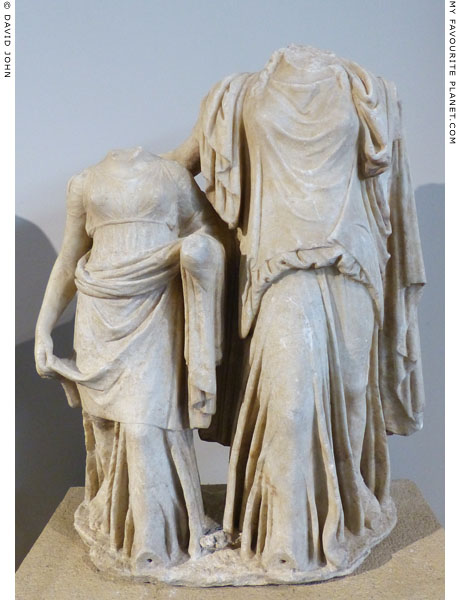

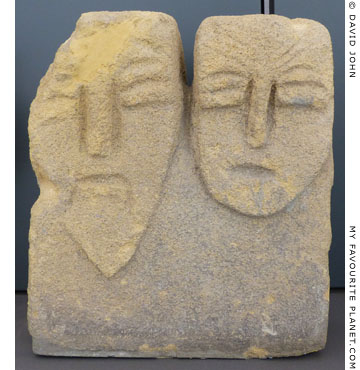

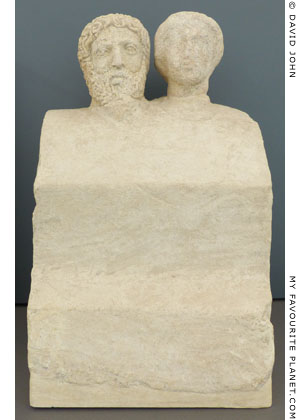

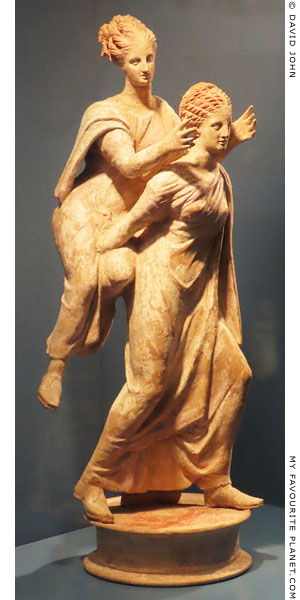

A marble statue group of Persephone (left) and Demeter.

From the sanctuary of Demeter at Derveni, the area of the ancient

Mygdonian city of Lete (Λητή), near Thessaloniki, Central Macedonia,

Greece. Late 4th - early 3rd century BC. Height 60 cm.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1070.

|

The two figures face the front and are stepping forward, Demeter, the larger figure on the right, leads with the right foot, and Persephone with the left. Both are now headless and missing their feet which were made separately. Demeter wears a peplos folded in a kolpo at the waist, and a himation (cloak) draped over her shoulders. Her left arm is missing, her right hand rests on Persephone's right shoulder. The daughter wears a himation over a long chiton (tunic). Part of the himation is draped around her left arm, and lifts anothe part of it with her right hand.

Demeter was worshipped at the shrine in her two aspects, as a mother and a virgin. Artemis, the daughter of Leto, after whom the city was named, was worshipped at the same shrine.

See also a statue thought to be from the sanctuary of Demeter at Derveni in Part 2. |

|

| |

Inscribed offering table dedicated to Demeter by "Stratto, daughter of Nikostratos, Melis,

daughter of Kleon, and Lysidike, daughter of Antigonos, at the time when Berenikas was

her priestess." The young girls, having served the goddess, were now free to marry.

From the sanctuary of Demeter, Derveni, area of ancient Lete, Macedonia. Late 4th century BC.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 1753. |

| |

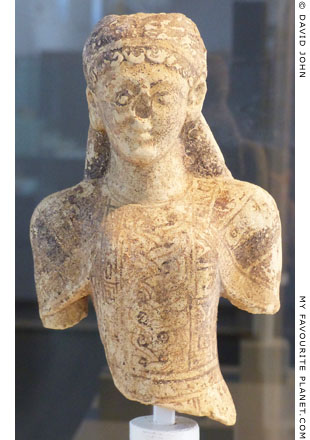

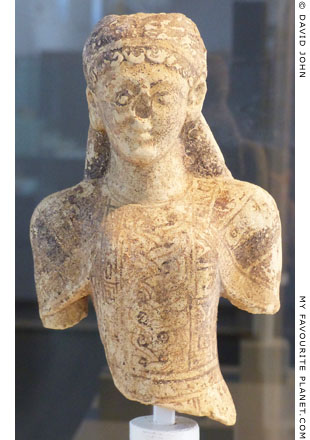

Terracotta bust of a goddess,

probably Demeter, from Olynthos,

Halkidiki, Macedonia, Greece.

End of the 5th century BC. It was

hung on a wall in a private house.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. |

|

A gilt bone plaque with a relief of

Demeter, Persephone or Hekate

seated, with a torch in her right hand.

Part of the decoration of a wooden

couch. From Tomb C, a cist grave at

Sedes, Macedonia, Greece. 320-300 BC.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. MΘ 19678. |

|

| |

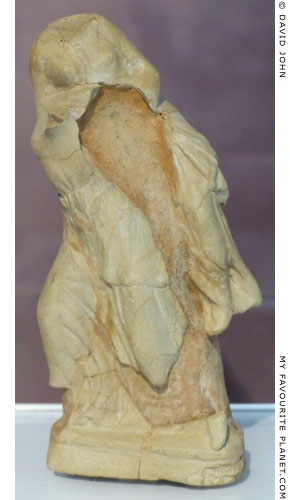

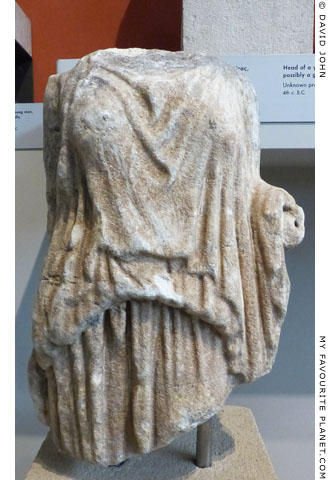

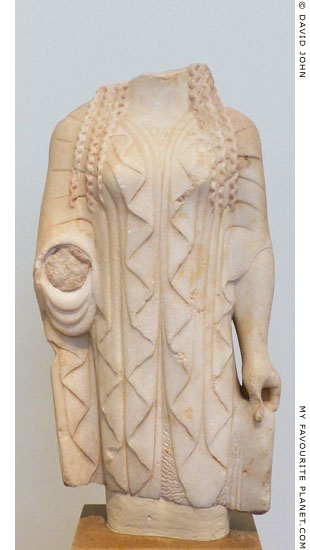

Fragment of a marble statuette of a female

figure wearing a peplos, possibly Demeter.

Early 4th century BC. From Agia Kyriaki,

Sochos (Σοχός), Macedonia, Greece.

The ancient settlement of Sochos was near the

modern town of Lagada, east of Thessaloniki

and north of Lake Volvi (the ancient Thracian

area of Bisaltia). Not much is known about its

history. It may have had a sanctuary of Hermes

and have been a centre of pottery production.

Thessaloniki Archaeological Museum. |

|

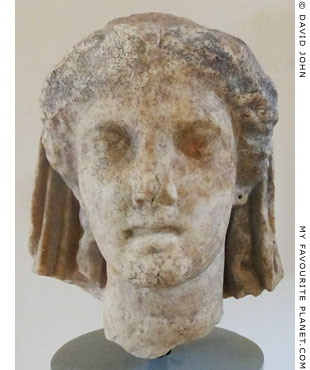

Marble head of Demeter, discovered

in 1973 in the sanctuary of Demeter,

Dion, Macedonia. 4th century BC.

Dion Archaeological Museum.

Inv. No. 200.

The sanctuary of Demeter in Dion is one

of the oldest places of worship of the

goddess in northern Greece, and temples

for her were built here from at least the

Archaic period. The sanctuary included

smaller buildings and altars for the worship

of other deities associated with fertility and

the underworld. From the 4th century BC

Demeter was worshipped there as

the syncretic deity Isis-Demeter.

For further information about the sanctuaries

of Demeter and Isis at Dion, see:

Dion: the garden of the gods

at The Cheshire Cat Blog.

See also a marble relief of Isis-Demeter

from Dion in Part 2. |

|

| |

Small terracotta jugs left as votive offerings at the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore,

Abdera, Thrace, northeastern Greece.

Abdera Archaeological Museum. |

|

Terracotta statuette of an enthroned

goddess, probably Demeter, from the

sanctuary of Demeter and Kore, Abdera.

4th century BC.

Abdera Archaeological Museum. |

|

| |

| |

Sanctuaries of Demeter and Persephone

Thesmophorion, Pella, Macedonia |

|

|

The remains of the Thesmophorion of Pella, Macedonia.

|

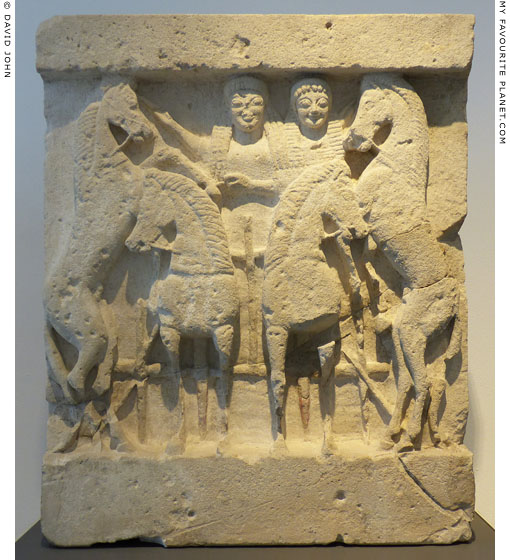

The Thesmophorion (Θεσμοφορίων), on the northeast edge of the modern village of Pella, is a circular enclosure with a diameter of 10.2 metres, built with cut rectangular blocks. It was entered by two sloping ramps leading down from either side, one of which can be seen in the centre of the photo above. In the middle stood an altar, constructed of alternate layers of crushed stone and clay, around which were found a large number of vases and ceramic votive figurines, including figures of deities such as Plouton, Artemis, Dionysus and Pan. Circular and rectangular pits in the ground acted symbolically as the underground chambers (μέγαρον, megaron, dwelling place; plural, μέγαρα, megara) of Demeter, in which the bones of young pigs and goats were found.

The site was excavated 1980-1981 by the Greek archaeologist Dr. Maria Lilimpaki-Akamati who published the results of her investigations in 1996. [19] Materials and finds include 59 coins, the oldest being bronze coins of Philip II (ruled 359-336 BC), and the majority are bronze coins of Cassander (316-297 BC) and Demetrios II (239-229 BC). This suggests that the rural sanctuary was in use from the second half of the 4th century BC, and reached the peak of its activity during the 3rd century, but was gradually abandoned following the Roman conquest of 168 BC. Due to uncertainty concerning the course of the city wall around this part of ancient Pella, it is not known whether the sanctuary stood in or outside the city's boundaries.

The three day festival of the Thesmophoria (Θεσμοφόρια) was celebrated every autumn, just before sowing time, when the women of the community took part in rituals and sacrifices, mostly dedicated to Demeter, to ensure the annual regeneration of nature, divine protection of their crops and a successful harvest. The sacrificed animals, as well as pine shoots and bread-dough cakes shaped like snakes and phalluses, were buried in the megara to decompose and mix with the fertilizing forces of nature. The remains were later removed from the pits by women known as "bailers" (ἀντλήτριαι, antletriai) and placed on the altar, where they were mixed with other fertility-related offerings and the grain seeds for sowing before being scattered over the fields. [20] |

|

| |

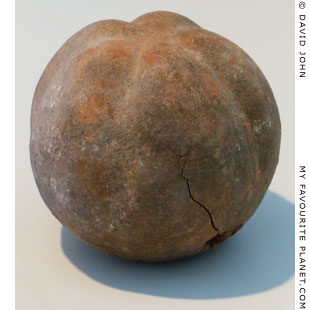

Terracotta votive figurine of a pig from the area

of the Thesmophorion, Pella, Macedonia.

This Macedonian pig looks wilder and hairer than the chubby,

naked, domesticated animal from Eleusis (see above).

Pella Archaeological Museum. |

| |

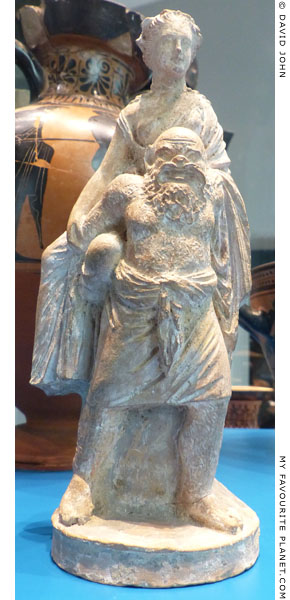

Terracotta votive figurine of Demeter and Persephone

from the Sanctuary of the Mother of the Gods and

Aphrodite in Pella, Macedonia. 4th - 1st century BC.

Pella Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

Sanctuaries of Demeter and Persephone

Malophoros, Selinous, Sicily |

|

|

The Sanctuary of Demeter Malophoros, Selinous (Selinunte), Sicily. |

| |

The ancient Greek colony of Selinous (Σελινοῦς; Latin, Selinus; today, Selinunte), on the southwestern coast of Sicily, was founded around 650-628 BC by Greeks from Megara, on the Isthmus of Corinth, who had founded the Sicilian city of Megara Hyblaia (Μέγαρα Ὑβλαία) about a hundred years earlier. The centre of the city and its acropolis were on a plateau over 30 metres above the shore, between the rivers Selinos (today the Modione) to the west and the Calici (Gorgo di Cotone) to the east, at the mouths of which were the city's two harbours (see map below).

It has been suggested that the small Hellenistic temple on the acropolis known as Temple B, previously thought to be a heroon for the philosopher Empedocles, was a temple of Demeter or Asklepios-Eshmun.

On another plateau, known as the East Hill, to the east of the deep valley of the Gorgo di Cotone river, and near the entrance to the archaeological site, are the remains of three large Doric temples (Temples E, F and G), built between 560 BC and 409 BC when the Archaic city was destroyed by the Carthaginian general Hannibal Mago, son of Gisco (not to be confused with the later, more famous Hannibal Barca who crossed the Alps with elephants to invade Rome). Temple E, built around 490-450 BC (opinions differ on exact dates) and probably dedicated to Hera, was restored in 1958 and has become the trademark of the Selinunte Archaeological Park, which claims to be the largest archaeological site in Europe.

The area known as Contrada Gaggera, the hill on the west side of the Selinos (Modione) valley, around 1 kilometre west of the acropolis, marked the western limit of the city. Along the east side of the hill facing the river were a number of smaller temples and sanctuaries, including the Sanctuary of Malophoros (see photo and description below).

Malophoros (Μαλοφόρος) as an epiphet of Demeter is known from a mention by Pausanias of the sanctuary of Demeter Malophoros in Megara, the metropolis (mother city) of Megara Hyblaia. The name has been translated as Sheep-bearer, Apple-bearer or Pomegranate-bearer, due to similarites of the words for sheep and apple in ancient Greek.

"When you have gone down to the port [of Megara], which to the present day is called Nisaea, you see a sanctuary of Demeter Malophorus (Sheep-bearer or Apple-bearer). One of the accounts given of the surname is that those who first reared sheep in the land named Demeter Malophorus." [21]

The translation of malo as apple is based on the idea that the goddess was seen as the bringer not just of cereal agriculture to mankind but also the cultivation of fruits such as the apple. The pomegranate is known to have been associated with the myth of Persephone, and another epiphet for Demeter, known from Greek inscriptions at several locations (Athens, Tegea, Ephesus, Pessinus, Aigeai, Pergamon, Sardis), was Karpophoros (Καρποφορος; also Karpotrophos, Καρποτροφος), Fruit-Bringer.

Many of the architectural members, sculptures and other finds from the temples are now in the Palermo Archaeological Museum (see the metopes below), the site's own small museum and the even smaller (one room) Museo Civico in the nearby town Castelvetrano (12 km northwest of Selinunte). |

|

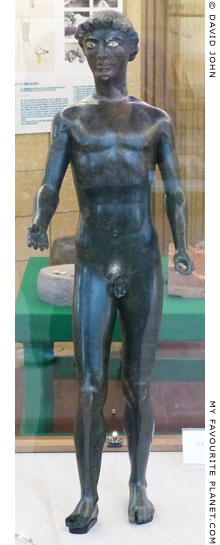

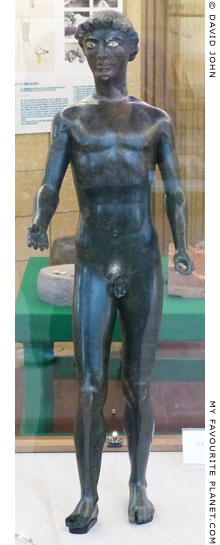

The Ephebe of Selinunte, a

bronze statue of a youth,

found in the area of Ponte

Galera, Selinunte in 1882.

According to a recent theory,

the figure may represent

Dionysus-Iakchos, associated

with the Eleusinian Mysteries.

480-460 BC. Height 84.7 cm.

Museo Civico, Castelvetrano,

Sicily. Inv. No. C/v 938. |

|

| |

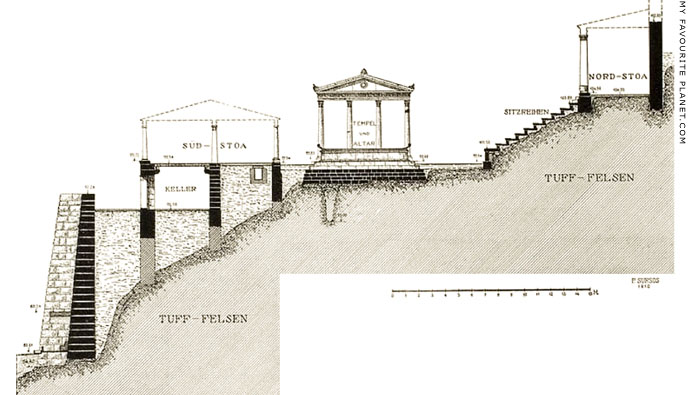

An idealized reconstruction of the Sanctuary of Malophoros, Selinous by Jean Hulot, 1910. [22] |

| |

Scale model of the Sanctuary of Malophoros, Selinous, viewed from the east side.

Cork model by Paolo Lipari. Scale 1:100.

Baglio Florio Museum, Selinunte Archaeological Park, Sicily.

See also the plan of the sanctuary below.

|

The Sanctuary of Malophoros, a rectangular area of around 50 x 60 metres, was originally an open-air sanctuary without buildings. The earliest finds are from the 7th century BC, suggesting it was founded soon after the Greek colonists arrived.

Discovered in 1871, the site was excavated by Francesco Saverio Cavallari in 1874, Giuseppe Patricolo in 1888, Antonino Salinas in 1894 and by Ettore Gabrici 1915-1926. Since then archaeological investigations have been intermittent, including "Mission Malophoros" 1983-1985, and more recently the partial restoration of the propylon in 2015, during which the remains were surveyed with a 3D laser scanner as well as by more conventional techniques.

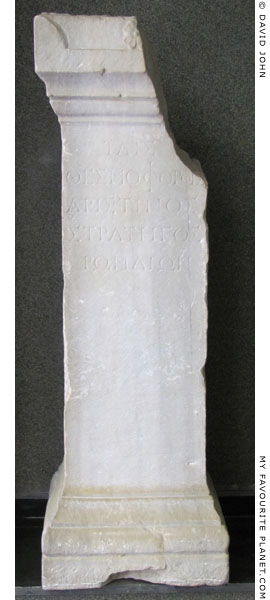

The sanctuary was identified by two inscriptions dedicated to Malophoros and Hekate (see photos below), as well as the enormous number of votive offerings of types known from other sanctuaries of Demeter in Sicily, including bronze statuettes, incense burners, lamps, ceramic vessels, jewellery, iron tools, various objects of bone, ivory and faience, along with around twelve thousand terracotta figurines, dating from the 7th to the 5th century BC, most depicting a female figure holding an apple or pomegranate.