|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English > Europe > Greece > Attica > Athens > galleries > Acropolis |

|

| |

The Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos below the south wall of the Acropolis. |

| The Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos |

| |

| The building above the monument, on the southern edge of the Acropolis, is the Old Acropolis Museum (see gallery page 29). This photo was taken from the terrace of the New Acropolis Museum. |

|

|

| |

Remains of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos, built 320/319 BC, above

the Theatre of Dionysos (see next page), on the south side of the Acropolis. |

| |

The Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos was set up in 320/319 BC by Thrasyllos of Dekeleia [1] to celebrate his victory as choregos (χορηγός), the sponsor of a chorus in the annual dramatic and choral contests of the Dionysia, the festival in honour of Dionysus.

The monument was built around a natural hollow in the rock, cut away to form a cave 6.2 metres deep and 6 metres high, just below the south wall of the Acropolis and above the Theatre of Dionysos. It is thought that the cave was sacred long before the construction of the monument, and may have been dedicated to Artemis.

The rock-face was cut back to form a flat vertical surface (known as the Katatomé), and the mouth of the cave was enlarged into a rectangular opening. Two broad stone steps lead up to the cave (see plan below).

Over the front of the cave a marble Doric portico was constructed, 7.7 metres wide and 8.4 metres high, in imitation the west facade of the southwest wing of the Propylaia of the Acropolis. [2] Three pilasters (70 cm wide, the central pilaster 52 cm wide) supported enormous doors and an entablature consisting of a relief of a row of eleven olive wreaths above an architrave inscribed with Thrasyllos' dedication. [See note 3 for the texts of the monuments' three inscriptions in Greek and English.]

One of the pilaster capitals, made from a single block of Pentelic marble, was rediscovered in 1985 in a storeroom of the National Museum, Athens. [4]

Above the monument three steps (which may have been added at a later date) were cut into the rock, leading to a platform on which the bronze tripod awarded as the prize for the contest was displayed.

Prize tripods were usually inscribed with the name of the winning choregos, the archon serving at the time of the contest and those who took part in the production. |

|

The two Corinthian columns of

the Roman period which stand

on top of the Choragic Monument

of Thrasyllos, as seen from the

southern parapet of the Acropolis,

near the Parthenon.

See also photos below. |

|

|

In 271/270 BC Thrasyllos’ son, Thrasykles, added two blocks of Hymettian marble to the top of the monument. Each of the blocks bore a further dedicatory inscription to celebrate choragic victories of his tribe, Hippothontis, in contests for which he was agonothete, a presiding officer. Presumably, two more choragic tripods were placed on top of these blocks. The monument may have been altered and enlarged to its final size at this time.

The tripods are thought to have been later replaced by or set up on three statues, of which only the central statue was to be seen still standing on the monument by foreign visitors to Athens in the 17th to late 18th century. The statue, thought to depict Dionysus (see photo, right), was removed in 1805 by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Lusieri, an employee of Lord Elgin, and is now in the British Museum [5], part of the "Elgin Marbles". [5]

The other two statues may have been replaced by the two Roman period columns, also erected for the display of choragic tripods, which still stand above the cave (see photo, above right). They are of different lengths, but both are made of Pentelic marble, stand on stepped plinths and have three-sided Corinthian capitals. On the plinth of the taller, eastern column is part of an inscription ".. χος Στρατόνεικος" (... chos Stratoneikos), which may be the name of the person who dedicated the tripod.

The monument is can clearly be seen on a 3rd century AD Athenian bronze coin showing the Acropolis and the Theatre of Dionysos (see Acropolis gallery page 36).

In the 2nd century AD the Greek travel writer Pausanias noted the presence of the monument, referring to it merely as a cave, without mentioning its appearance, architectural form or adornments:

"On the South Wall, as it is called, of the Acropolis, which faces the theatre [of Dionysos], there is dedicated a gilded head of Medusa the Gorgon, and round it is wrought an aegis.

At the top of the theatre is a cave in the rocks under the Acropolis. This also has a tripod over it, wherein are Apollo and Artemis slaying the children of Niobe.

This Niobe I myself saw when I had gone up to Mount Sipylus. When you are near it is a beetling crag, with not the slightest resemblance to a woman, mourning or otherwise; but if you go further away you will think you see a woman in tears, with head bowed down." [6]

Pausanias makes no mention of a statue or statues at the monument, which may mean that they had not been placed there by the time of his visit to Athens, or merely that he did not find the statue(s) worth writing about.

Above and to the right of the monument stands an ancient marble sundial (see photo below).

During Byzantine times the cave of the monument was converted into a Christian chapel known as Panagia Spiliotissa (Παναγία Σπηλιώτισσα, Virgin of the Cave). [7]

In 1395, Νiccοlo da Martoni, a notary from Capua, visited Athens on his return to Italy from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and was shown the two columns of the monument. He was told that between them formerly stood an idol which had the power to sink hostile ships as they appeared on the horizon. [8] The idol was probably the gilded head of the Gorgon Medusa mentioned by Pausanias, which was hung on the south wall of the Acropolis (see above).

From the 17th century several scholarly European visitors to Athens noted the monument, its sculptures and inscriptions and made conjectures about its age and significance. [9]

The remains of the monument were studied by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett during their stay in Athens 1751-1753 (see Acropolis gallery page 12). They measured and made drawings of the monument and translated the inscriptions (see illustrations below).

Once again, as in the case of the Ilissos Temple, Stuart and Revett's painstaking study of some of the minor monuments of Athens, a labour crtitcized at the time, was later to be vindicated: in 1827 the monument was destroyed by artillery fire during the Turkish siege of Athens by Kütahı Pasha, in the Greek War of Independence, and the drawings and description are now the main source of the monument's pre-1827 condition for restoration workers.

The taller of the two columns above the monument has a large hole (visible in the photo above) probably caused by the Turkish bombardment.

Apart from the removal of the Dionysus statue by Elgin, other parts of the monument were controversially taken during the 19th century to be used in the building of the Russian Orthodox Church on Filellinon Street.

Although the first plans to restore the monument were made in the 19th century, restoration work did not finally get underway until 2003, when the Central Archaeological Council (KAS) approved the model study by architect and renovator Constantinos Boletis. [10]

At the time of my last visit in late 2015, the restoration work still looked nowhere near completion.

Further down the slope, to the west of the theatre, are the foundations of the Choragic Monument of Nikias, built around 320/319 BC in the form of a prostyle hexastyle Doric temple with the entrance at the west end. Parts of this monument were used to build the late Roman Beulé Gate to the Acropolis in 280 AD (see Acropolis gallery page 6).

The most famous collection of tripods in ancient Athens was in the Street of the Tripods (Οδός Τριπόδων, Odos Tripodon), which, according to Pausanias, was lined with the trophies from the area of the Prytaneion, north of the Acropolis, to the Theatre of Dionysos. The Choragic Monument of Lysikrates, erected in 335/334 BC, can still be seen on Odos Tripodon in the Plaka district (see photo on Acropolis gallery page 6).

|

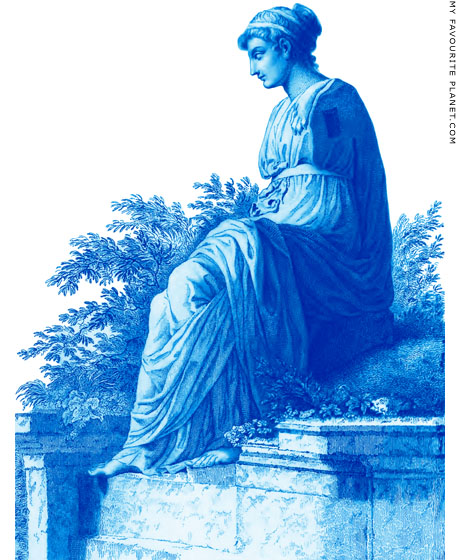

Marble statue of Dionysus from the

Monument of Thrasyllos. 3rd - 2nd

century BC. Height 190 cm.

British Museum, London. [5]. |

| |

Reconstruction of the Dionysus statue on top

of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos.

Source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett,

The antiquities of Athens, measured and

delineated, Vol. II, Chapter IV, plate 38,

fig. 2. Priestley and Weale, London, 1825.

At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

A reconstruction drawing of the Thrasyllos

Monument as it may have appeared in the

3rd-2nd century BC. The artist has added

a tripod on either side of the entablature,

with the Dionysus statue in the centre.

Source: Hermann Luckenbach,

Die Akropolis von Athen, page 46.

R. Oldenbourg, Munich and Berlin, 1905.

At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

|

The Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos below the east side of the Parthenon and the

south walls of the Acropolis. At the bottom left corner of the photo are the remains of

the upper tiers of seating of the Theatre of Dionysos, now overgrown with grass.

The low building to the right of the Parthenon is the Old Acropolis Museum.

This photo was taken during the restoration work in 2011.

The reconstruction work was still incomplete in August 2015. |

| |

The Corinthian columns above the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos. Roman period. |

| |

A drawing of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos by Julien-David Le Roy [11]. |

| |

This engraving of Le Roy's drawing shows how the space between the monuments' pilasters was walled up with large stone blocks during its conversion to a Christian chapel.

The headless Dionysus statue and the three dedicatory inscriptions of the monument are clearly visible. The oldest and largest, by Thrasyllos in 320/319 BC, is just above the central pilaster. The two later inscriptions, by his son Thrasykles in 271/270 BC, are either side of the Dionysus statue. [See note 3 and the drawings by Stuart and Revett below].

The sundial, standing on the rock to the right of the cave, has been made to look much larger than its actual size.

Julien-David Le Roy, Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce, Premiere Partie (Part 1), Plate VIII. Paris, 1758.

At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Dr. Richard Chandler, who saw the sundial during his visit to Athens in 1765-1766, wrote that it had been "moved awry from its proper position" (Travels in Greece, page 63, see note 5). |

The marble sundial to the right of

the Monument of Thrasyllos. |

| |

Another marble sundial found

at the Theatre of Dionysos.

Probably Roman period.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 3156. |

| |

| |

The Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos as seen by James "Athenian" Stuart, during his stay in Athens

with Nicholas Revett, 1751-3 (see Acropolis gallery page 12). At this time, the Theatre of Dionysos

had not yet been rediscovered as it was buried by earth and rubble at the foot of the Acropolis,

just below the Thrasyllos Monument (in the bottom right of the picture).

Image source: Hermann Luckenbach, Die Akropolis von Athen, page 49.

R. Oldenbourg, Munich & Berlin, 1905. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

|

"The distant mountain is part of Hymettus. Nearer in the shade, directly under the highest point of Hymettus, is the church of St. George the Alexandrian [see below]. The little building still nearer, with a cupola, is the church of Hagia Parasceve [Agia Paraskevi]. Between this and the rock appears at some distance a metochi, or farm, belonging to the convent of Hagio Asomato [monastery of Agios Asomatos].

The eastern end of the south side of the Acropolis occupies the left-hand side of the view. The rock on which it was built is lower here than in any other part of its circuit. Against the rock stands the choragic monument of Thrasyllus and Thrasycles; near which three Greeks are waiting the arrival of the Pappas [priest], attended by a boy who carries a wax-candle, followed by a man and a woman leading a child, who, with those already mentioned, made this whole congregation.

Higher up on the rock stand the two columns with triangular capitals. On each side the monument the rude rock has been chiselled into a regular surface, that other little buildings, which, I imagine were also choragic monuments, might be conveniently placed against it.

Over the head of the Greek who is sitting down to wait the coming of the Pappas, is the sun-dial."

James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume II, pages 90-91. P. Priestley and Weale, London, 1825. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

An engraving from the watercolour is printed in this edition as Plate XXXVII, fig. 1. |

|

|

| |

The small chapel of Saint George Alexandrinos (Άγιος Γεώργιος ο

Αλεξανδρινός, Agios Georgios o Alexandrinos), to the east of the

Theatre of Dionysos, below the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos.

|

Looking more like a roughly-built hut, the chapel was constructed on the site of the Byzantine church of Saint George Alexandrinos (Saint George the Alexandrian), built in the 11th or 12th century, and destroyed in 1826, during the Turkish siege of the Acropolis (August 1826 - May 1827). According to accounts by the Greek defenders, they blew the church up after luring Turkish soldiers to it. The Turkish bombardment of the Acropolis caused more damage to the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos and other monuments.

The chapel stands directly to the east of the Theatre of Dionysos, in the area of the Odeion of Pericles (see images and plans on gallery page 36). This is much further down the hill than the location of the church as shown on James Stuart's view of the area around the monument (see above).

Stuart also drew and described the Late Byzantine chapel of Agia Paraskevi (Αγία Παρασκευή) as being quite near the Thrasyllos monument. However, modern plans and descriptions of the area around the theatre place the ruins of the chapel much further downhill, to the south of the Sanctuary of Dionysos Eleuthereos, on the edge of Dionysiou Areopagitou Street. This building, of which only the foundations have survived, was built over an earlier temple. |

|

|

| |

Plan of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett.

Image source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens,

measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter IV, plate XXXVII, fig. 2. Priestley and

Weale, London, 1825 (first published 1787). At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

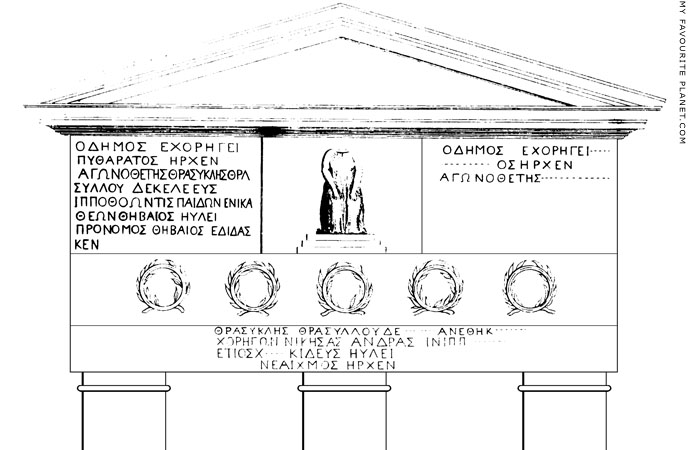

Reconstruction of the facade of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos by James Stuart.

The head and arms of the statue were already missing, and replaced in the drawing

for aesthetic reasons.

"I have ventured to restore the head, since without it the reader would not

so readily have formed a just idea of the elegance of this figure." James Stuart.

Source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated,

Volume II, Chapter IV, plate III. Printed by John Nichols, London, 1787. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

For a later edition of Stuart and Revett's The Antiquities of Athens,

the above reconstruction was reduced to a more rational line-drawing.

The quality of the engravings illustrating the first editions of James Stuart's magnum opus

was of a much higher quality, with a wide range of tones and clear fine details. The later

editions were re-edited and prepared for publication after his death, when many of his

drawings could not be found among the chaos of his papers. Presumably, the original

printing plates were also lost, or else it was decided to cut costs with simpler engravings.

Image source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens,

measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter IV, plate XXXVIII, fig. 1.

Priestley and Weale, London, 1825. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

James Stuart's reconstruction of the Dionysus statue on top of the

Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos, as it appeared in the first edition

of his Antiquities of Athens, Volume II, 1787. He not only restored

the missing head but also gave it a decidedly feminine appearance,

since he believed the statue represented a female figure [see note 5].

Source: James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens,

measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter IV, pages 34-36,

plate VI. Printed by John Nichols, London, 1787. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

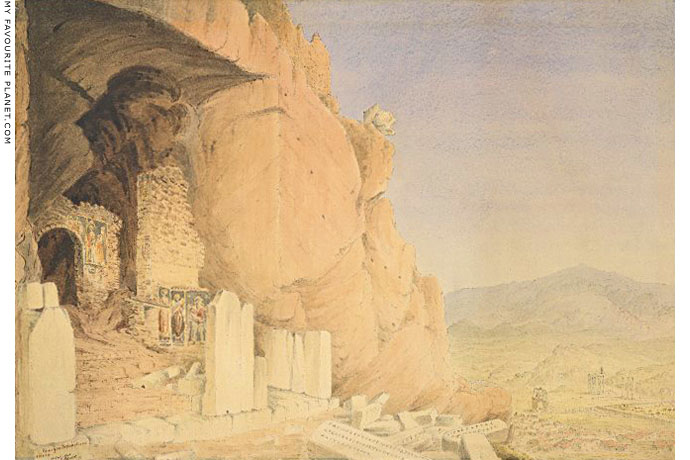

Drawing made in 1840 by Scottish artist James Skene (1774-1864) of the ruins of the Choragic

Monument of Thrasyllos following the Turkish bombardment of the Acropolis in 1827.

Within the cave are the remains of the Byzantine chapel of Panagia Spiliotissa. An arch and panels

(or a screen?) to its right are covered with Byzantine paintings. At the mouth of the cave stand

the shattered pilasters of the Hellenistic monument, to the right of which lie parts of the inscribed

architrave. In the background (right): the Arch of Hadrian, the Temple of Olympian Zeus (Olympieion)

and Mount Hymettos (Ymittou).

Graphite, pen and brown ink, and watercolour.

Signed: "Panagia Sepoliotissa / Athens. / 16 Oct 1840. J. Skene."

Image source: © The Trustees of the British Museum |

| |

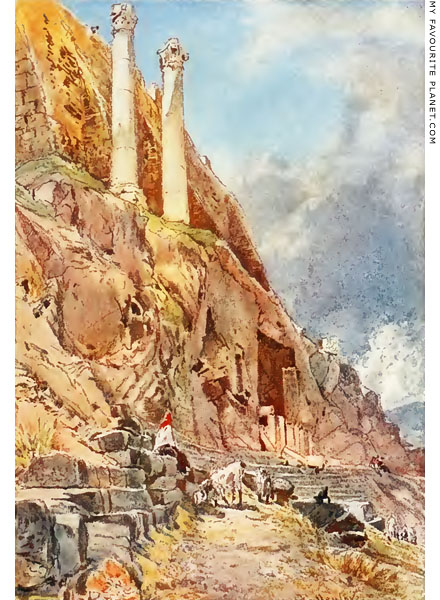

Engraving from a watercolour of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos

by the English landscape artist John Fulleylove (1845-1908). In the

foreground a shepherd or shepherdess, wearing a red headscarf,

tends sheep grazing on the South Slope of the Acropolis.

Image source: Rev. James Alexander M'Clymont, Greeece,

with paintings by John Fulleylove, plate 64, opposite page 190.

A. & C. Black, London, 1906. At the Internet Archive. |

| |

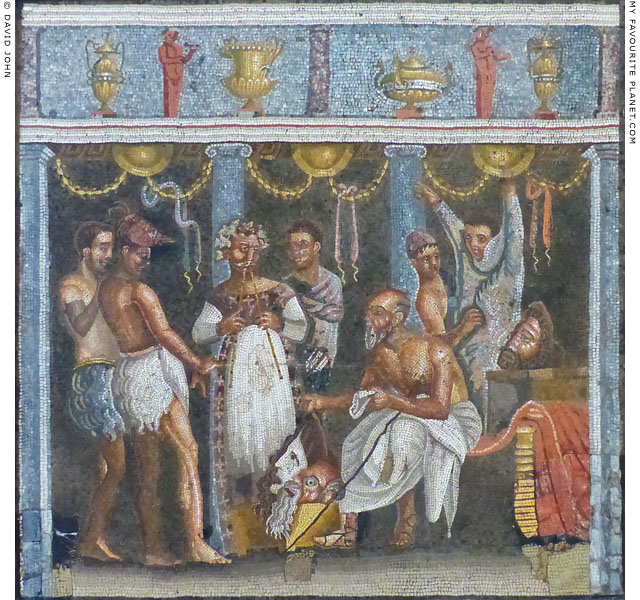

The "Satyr Play mosaic" from Pompeii, depicting a choregos distributing masks to his actors

as they prepare for a performance. Much speculation has been made about the figures

and costumes depicted, and whether the players are dressing for a tragedy or a comedy.

Attempts have even been made to identify the specific play, and it has been suggested

that the "choregos" figure may be a playwright, perhaps Aeschylos or Aristophanes.

End of the 1st century BC. Found 2nd March 1825 in the tablina of the House of

the Tragic Poet (Casa dell Poeta Tragico, VI, 8, 3), Pompeii. Circa 40 x 40 cm.

National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Inv. No. 9986. |

| |

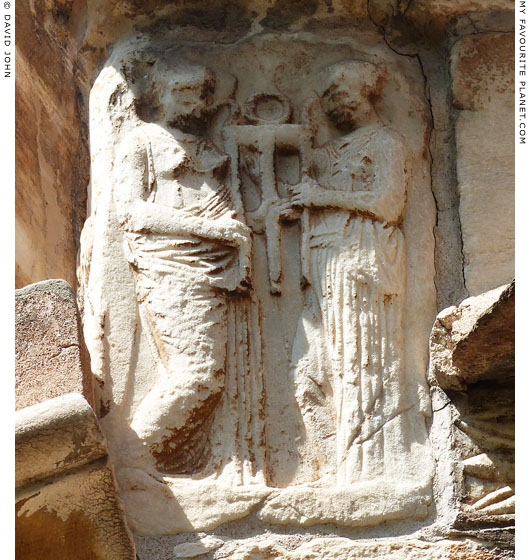

A marble relief of two female figures holding a tripod. Built into the wall at

the east end of the Byzantine Little Metropolis church in central Athens.

The small Byzantine church of Panagia Gorgoepikoos (Παναγία Γοργοϋπήκοος, the

swift-hearing Virgin), also known as the Little Metropolis (Μικρή Μητρόπολη, Mikri

Mitropoli), and for a short while renamed as the church of Agios Eleutherios (Άγιος

Ελευθέριος), acted as the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens during the Turkish

occupation, until the much larger modern cathedral was built next to it 1842-1862.

It is not known when the church was built, perhaps as early as the 9th century

or as late as the 15th century. It was constructed using marble spolia, material

from various older pagan and Christian buildings, so that its walls are covered

with a variety of reliefs and inscriptions from different periods. Ancient inscriptions

were also housed inside the church, as well as a Roman period sundial, which is

now in the British Museum (see gallery page 36). Attempts have been made

to identify the parts of ancient reliefs built into the walls of the church.

For further information see Demeter and Persephone part 1. |

| |

Choragic Monument

of Thrasyllos |

Notes, references, links |

|

|

On this page I have used the usual English spelling for Dionysus, except where the name is used in a quotation or as a title such as Theatre of Dionysos, Sanctuary of Dionysos or Dionysos-Sardanapalos (also referred to as Dionysus-Sardanapalus).

The tradition of using Latinized versions of ancient Greek names seems very outdated, but attempting to correct every instance (Akropolis for Acropolis, Attalos for Attalus, Korinth for Corinth, Perikles for Pericles, etc) can lead to all kinds of complications and muddles.

1. Dekeleia was a rural deme of Athens, situated to the northeast of the city.

2. Imitation of the Propylaia in the choragic monuments Thrasyllos and Nikias

See:

Rhys F. Townsend, Classical signs and anti-Classical signification in 4th century Athenian architecture, in Anne Proctor Chapin (editor), Xaris essays in honour of Sara A. Immerwahr, Chapter 16. Hesperia Supplement 33, The American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), 2004. Preview at googlebooks.

3. Inscriptions on the Thrasyllos Monument

The remains of the three inscriptions are now in the Athens Epigraphical Museum, part of the National Archaeological Museum.

See the position of the three inscriptions in the illustration by Stuart and Revett above.

The oldest inscription, on the architrave directly above the doorway, was dedicated by Thrasyllos who erected the monument following his choragic victory in 320/319 BC.

Θράσυλλος Θρασύλλου Δεκελεεὺς ἀνέθηκεν

χορηγῶν νικήσας ἀνδράσιν Ἱπποθωντίδι φυλῆι ⋮

Εὔιος Χαλκιδεὺς ηὔλει. Νέαιχμος ἦρχεν ⋮ Καρκίδαμος Σώτιος ἐδίδασκεν.

"Thrasyllos, son of Thrasyllos of Dekeleia, set this up,

being choregos and winning in the men's chorus for the tribe of Hippothontis;

Euios of Chalcidis played the flute. Neaichmos was the Archon. Karkidamos son of Sotios directed."

Inscription: IG II² 3056

The two later inscriptions, commissioned by Thrasyllos' son Thrasykles in 271/270 BC, are on blocks of Hymettian marble set above the frieze, to the left and right of the presumed position of the tripod of Thrasyllos. Since the tripods have long since disappeared, the positions of these inscriptions are usually stated in relation to the statue of Dionysus (see note 5).

base A, left of the Dionysus statue:

ὁ δῆμος ἐχορήγει, Πυθάρατος ἦρχεν.

ἀγωνοθέτης Θρασυκλῆς Θρασύλλου Δεκελεεύς.

Ἱπποθωντὶς παίδων ἐνίκα.

Θέων Θηβαῖος ηὔλει.

Πρόνομος Θηβαῖος ἐδίδασκεν.

"The demos was choregos, Pytharatos was archon.

Thrasykles, son of Thrasyllos of Dekeleia, was agonothete.

Hippothontis won the boys' chorus.

Theon the Theban played the flute.

Pronomos the Theban directed."

base B.5a, right of the Dionysus statue:

ὁ δῆμος ἐχορήγει, Πυθάρατος ἦρχεν.

ἀγωνοθέτης Θρασυκλῆς Θρασύλλου Δεκελεεύς.

Πανδιονὶς ἀνδρῶν ἐνίκα.

Νικοκλῆς Ἀμβρακιώτης ηὔλει.

Λύσιππος Ἀρκὰς ἐδίδασκε.

"The demos was choregos, Pytharatos was archon.

Thrasykles, son of Thrasyllos of Dekeleia, was agonothete.

Pandionis won the mens' chorus.

Nikokles the Ambracian played the flute.

Lysippos the Arcadian directed."

Inscription: IG II² 3083

Thrasykles is described as the agonothete, a presiding officer at games and contests.

The line "The demos was choregos" has caused consternation among some scholars:

did the city itself finance the competitions at this time? Many doubt this.

"ἐδίδασκεν" has been translated variously as "directed", "taught the chorus" and

"composed the piece".

The inscriptions can be found at epigraphy.packhum.org in Greek only.

There are various translations, including those by Stuart and Revett:

James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter IV, pages 86-88. Priestley and Weale, London, 1825. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

See also: Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, Chapter 12, pages 62-64. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At the Internet Archive.

4. Rediscovered pilaster capital from the Thrasyllos Monument

The National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Inventory Number E.M Δ 970.

See: Rhys F. Townsend, A newly discovered capital from the Thrasyllos Monument. American Journal of Archaeology, Volume 89, No. 4 (October, 1985), pages 676-680. Archaeological Institute of America. At jstor.org. |

|

|

|

5. Statue of Dionysus from the Monument of Thrasyllos

in the British Museum

Inv. No. 1816,0610.111 (Sculpture 432).

Purchased for the British Museum in 1816 from Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin.

British Museum description: "3rd - 2nd century BC. Height: 1.9 metres. Marble statue of Dionysos seated on a rock, wearing a panther-skin and tunic; his head and arms are missing; his left arm once held a kithara. Probably from the choragic monument of Thrasyllos at Athens."

The dating of the statue is based on the theory that it was made and set up at the time of Thrasyllos or his son Thrasykles. As mentioned above, it is worth noting that Pausanias made no mention of this statue at the monument.

The statue was first reported by George Wheler, who visited Athens with Dr. Jacob Spon in early 1676. He decribed it as "a sedent figure, cloathed but without a head".

George Wheler, A journey into Greece in company of Dr Spon of Lyons, Book V, page 368. William Cademan, Robert Kettlewell, and Awnsham Churchill, London, 1682. At Googlebooks.

In Wheler's crude and inaccurate drawing of the monument (see below) the disproportionately tiny figure appears to have at least one arm. However, both arms were certainly missing by 1751-1753 when James Stuart saw it.

"The statue on top of the monument. The head and arms are wanting, they were originally separate pieces of marble mortised on to the body; this must have facilitated their removal, or their ruin."

James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, The antiquities of Athens, measured and delineated, Volume II, Chapter IV, pages 92-93 and plate XXXVIII. Priestley and Weale, London, 1825.

At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

William Martin Leake noted holes in the lap of the statue to which a tripod may have been affixed:

"The only point wherein the description of Pausanias appears deficient is, that it mentions a tripod above the cavern, without taking any notice of the statue of Bacchus, formerly seated upon the entablature of the small temple, and now in the British Museum. It is to be observed, however, that there are holes in the lap of that statue which indicate the position of a tripod, and that the custom of supporting tripods by statues was not uncommon."

William Martin Leake, The topography of Athens and the Demi, Volume I: The topography of Athens (The topography of Athens, second edition), Section II, page 186. J. Rodwell, London, 1841. At the Internet Archive.

Stuart had also expressed the opinion that the tripod won by Thrasyllos was placed on the knees of the statue. At one point he climbed onto the rock to get a closer look of the top of the monument, but was forced to retreat when irate Turks on the Acropolis began dropping stones on him (The antiquities of Athens, Volume II, page 89). Like other early travellers to Athens who saw this statue, he took it to represent a female figure, particularly as the high girdle gives the suggestion of a bosom. He suggested that it may have depicted a personification of the tribe of Hippothontis or its deme Dekeleia, to which Thrasyllos and Thrasykles belonged.

Dr. Richard Chandler, seeing the statue during his visit to Athens in 1765-1766, also believed it to represent a female figure. According to Stuart (The antiquities of Athens, Volume II, page 93), Chandler suggested that it was the depiction of Niobe mentioned by Pausanias (see above). Stuart disagreed with this opinion on the grounds that a famous statue of Niobe in Rome (now in Florence, part of the Uffizi Niobid Group) showed her standing anguished and apprehensive, whereas this statue "on the contrary, is seated with some dignity, and appears to be in a state of perfect tranquility", as well as what he called the "lion's skin" worn by the figure. He did not know that the Niobe on Mount Sipylus, also mentioned by Pausanias, is a seated figure (see photo below).

"In the rock above the theatre is a large cavern, perhaps an antient quarry, the front ornamented with marble pilasters of the Corinthian order, supporting an entablature, on which are three inscriptions. Over that in the middle, is a female figure, which which had lost its head in the year 1676, mounted on two or three steps, sedent."

Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, Chapter 12, pages 62-63. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At the Internet Archive. (All mentions of the year 1676 in Chandler's book refer to Spon and Wheler's visit to Athens.)

The identification of the statue as Dionysus, by no means certain, is based mainly on the association of the monument with the Theatre of Dionysos and the god's patronage of the theatrical arts, and the fact that the figure has around its shoulders the skin of an animal, taken to be a panther, an attribute of Dionysus (see images of Dionysus wearing an animal skin on the Dionysus page of the MFP People section).

Although several modern authors, writing about the Monument of Thrasyllos, state that it was dedicated to Dionysus, there appears to be no archaeological or literary evidence for this. Although our modern understanding of symbolism may demand that there be a statue of Dionysus atop his theatre, within his sanctuary, the nature and evolution of Greek sanctuaries was not always so straight forward. Smaller clusters of sanctuaries were often brought within the area of one cult centre as it grew in importance or demanded more space, which an expanding theatre certainly would. Such areas included, statues, temples, altars and dedications to several deities and mythical figures. The top of the theatre of Samothraki, for example, was dominated by the famous statue of the victory godess Nike (the "Winged Victory of Samothrace").

It is also far from certain that this statue was holding a kithara or lyre, and since its arms are missing it would be difficult to prove, especially as there is no other known statue of this type, showing Dionysus seated, dressed wearing such a long, voluminous garment and holding a stringed instrument; in fact the god is rarely shown dressed in this manner or playing an instrument.

The high relief sculpture of Dionysus on the west pediment of the Classical Temple of Apollo in Delphi (see photo and reconstruction drawing, above right) is thought to have portrayed the god holding a kithara in his left arm, although both arm and instrument are now lost. Like the statue on the Thrasyllos Monument, the Delphi sculpture shows the god wearing a long chiton, girdled high above the waist, and a himation (a large woollen blanket worn as a mantle or cloak) hanging from his shoulders.

According to the Delphi Museum labelling: "In the centre [of the frieze on the temple pediment] stands Dionysus, in the rare iconographic type of the cithara (type of lyre) player. ... The cithara he holds in his left hand places him on equal terms with the god of music, Apollo, and reconciles the different realms of the two deities who are both depicted on the same temple."

"Dionysos Sardanapalos" type statues, one of which was discovered in the Theatre of Dionysos (see photo below), are thought to be based on a Greek original of 350-300 BC. The type shows a standing figure, assumed to be Dionysus, wrapped in a himation, with his left arm within the garment, but with no panther skin or instrument.

The heavily restored Roman "Hope Dionysus" (27 BC - 68 AD, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Inv. 1990.247), which has the head of another statue, and the similar "Dionysus and Cora" (Hermitage, Saint Petersburg, "after a Greek original of the 4th-3rd century BC"), show a standing male figure with a big cat-skin draped around his shoulders and wearing a short chiton. Again, there is no sign of an instrument; the "Dionysus and Cora" shows the god holding grapes in his left hand.

There are some ceramic paintings showing Dionysus with a lyre, but in these he is usually standing or dancing, and is more lightly clad. One of the most famous examples is the Attic red-figured cup interior of Dionysus and satyrs by the Brygos Painter, circa 480 BC (Louvre, Paris, Inv. No. 575).

It has also been suggested the statue from the Monument of Thrasyllos depicts Apollo, as he was the great master of music and of the Muses who inspired poets (including dramatic poets) and musicians. He is often shown in Greek art playing a lyre or kithara, notably in the types of sculpture known as the "Apollo Kitharoedos" and "Apollo Lykeios" (see photo, below right).

Identifying and sexing ancient Greek and Roman sculptures has proved a tricky business, particularly Classical and Hellenistic portrayals of Dionysus and Apollo. The feminine features and hairstyles of many heads discovered have led archaeologists, art historians, museum directors and collectors to label them as female. See, for example, the head of the "Singing or talking Dionysus" (see photo below), which was long thought to be of a woman or female deity. An almost identical head from the Acropolis south slope, now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens (Inv. No. 182) is still labelled as "either Ariadne or Dionysos". |

| |

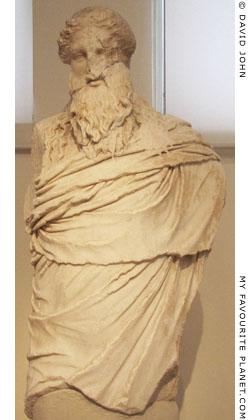

Pentelic marble statue of Dionysus of the

"Dionysos-Sardanapalos" type, found

in the Theatre of Dionysos, Athens.

1st century AD copy of the type "after

a Praxitelean original, circa 325-300 BC".

See Acropolis gallery page 36.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 1656. |

| |

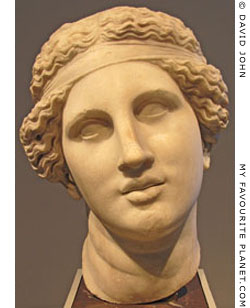

Marble head of a "singing" or "talking"

Dionysus, wearing the mitra headband.

Roman period. One of many copies

of a Hellenistic original (270-250 BC)

thought to be from the Athenian

Sanctuary of Dionysos.

Altes Museum, Berlin. Sk 610. |

|

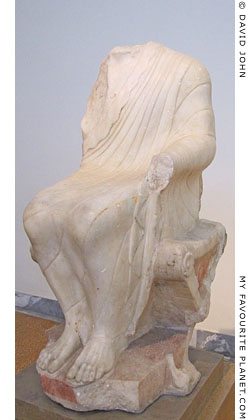

Another statue of a seated Dionysus

from Athens. The headless figure

wears a himation draped over his

left shoulder, leaving the right

shoulder bare. He is seated on a

folding stool, with lion's paw feet,

over which lies a panther skin.

Pentelic marble, about 500 BC.

National Archaeological Museum,

Athens. Inv. No. 3711. |

| |

High relief of Dionysus from the

west pediment of the Classical

Temple of Apollo, Delphi. Work of

the Athenian sculptors Praxias

and Androsthenes, circa 330 BC.

Delphi Archaeological Museum. |

| |

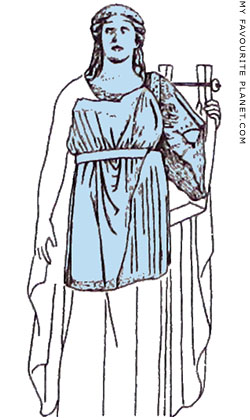

Reconstruction drawing of the

Dionysus relief from Delphi

(surviving parts in blue), showing

the god holding a kithara and

wearing a long chiton and himation. |

| |

Marble statuette of a standing

figure, now headless, wearing

a long chiton belted at the waist

and a himation, and holding

a kithara (?) in the left hand.

Identified as Apollo Patroos, and

thought to be a copy of a statue

by Euphranor (4th century BC).

From the Athenian Agora.

Agora Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. S 877. |

| |

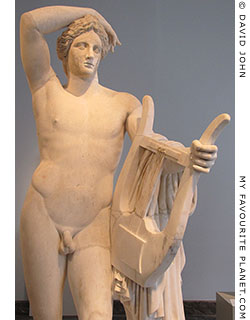

Statue of Apollo of the "Lykeios

type". Modelled either after an

original of the circle of Praxiteles

of circa 340 BC, or a Hellenistic

reworking of around 150 BC.

The god holds a kithara in his left

arm, his right forearm rests across

his head. The head and body

of two different Roman statues

combined in the 18th century.

Marble. Body around 140 AD.

Acquired in Rome in 1766.

Altes Museum. Berlin.

Inv. No. Sk 44. |

| |

|

6. Pausanias on the Monument of Thrasyllos and Niobe

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 1, chapter 21, section 3. English translation by W.H.S. Jones and H.A. Ormerod, in 4 Volumes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann, London, 1918. At Perseus Digital Library.

Further information about Pausanias in the MFP PEOPLE section.

"A gilded head of Medusa the Gorgon, and round it is wrought an aegis..." The aegis was a goatskin worn by Athena as armour, on which was affixed the severed head of the Gorgon Medusa. For further information about the relationship between Athena, the aegis and Medusa, see Pergamon gallery 2, page 13.

"Apollo and Artemis slaying the children of Niobe..." It is not clear whether this image was a painting, a relief or statue group. The theme was a popular motif in ancient art (see photo and text below).

Some scholars believe Pausanias may have come from Magnesia ad Sypilum (today Manisa, Turkey), the home of Tantalos and Niobe, as his references to this area are so detailed.

Later he describes a curtain in the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, saying that it was dedicated by Antiochus, who also gave the Gorgon on the golden aegis above the Theatre of Dionysos as a votive offering:

"In Olympia there is a woollen curtain, adorned with Assyrian weaving and Phoenician purple, which was dedicated by Antiochus, who also gave as offerings the golden aegis with the Gorgon on it above the theatre at Athens."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 5, chapter 12, section 4. At Perseus Digital Library.

Antiochus is thought to have been Antiochus IV Epiphanes (Ἀντίοχος Δ΄ ὁ Ἐπιφανής, Antiochos D' o Epiphanes, God Manifest, circa 215-164 BC), king of the Seleucid Empire (Ancient Syria) 175-164 BC.

Read more about the curtain at Olympia on the Medusa page in the MFP PEOPLE section. |

|

|

| |

The "Weeping Rock of Niobe" (Niobe Ağlayan Kaya) at the foot of Mount Sipylos (Sipil Daği),

on the outskirts of Magnesia ad Sypilum, Lydia (today the city of Manisa, Turkey).

|

In Greek myth Niobe (Νιόβη), daughter of Tanatalos and mother of many children (numbers differ in the versions of various ancient authors), taunted the nymph Leto who only had two - Apollo and Artemis by Zeus. Incited by their enraged mother, Apollo and Artemis killed Niobe's children (the Niobids) by shooting them with arrows. Niobe returned to Sipylos and wept an age for her loss, until Zeus put an end to her misery by turning to her into this rock.

It seems that even in the time of Pausanias the rock appeared to be naturally-formed and weathered. If it was sculpted in prehistory, the marks of human intervention had long-since been eroded away. With a bit of imagination and some serious squinting, one can see the form of a seated woman with bowed head and empty lap. To the left of the figure is a small cleft or niche from which today a tree grows.

According to local legend, the rock weeps every Friday, a miracle this author failed to witness. He did, however, notice that locals come to a nearby spring to fill enormous plastic containers with the water.

"Being blessed with children, Niobe said that she was more blessed with children than Latona [Leto]. Stung by the taunt, Latona incited Artemis and Apollo against them, and Artemis shot down the females in the house, and Apollo killed all the males together as they were hunting on Cithaeron... Niobe herself quitted Thebes and went to her father Tantalus at Sipylus, and there, on praying to Zeus, she was transformed into a stone, and tears flow night and day from the stone."

Apollodorus, The Library, Book 3, chapter 5, section 6. English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, in 2 Volumes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann Ltd., London, 1921. At Perseus Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

Decorative marble roundel with a relief depicting Apollo and Artemis slaying the children of Niobe.

Roman, probably 1st century BC. From Italy.

At the top Artemis (left) and Apollo (right, kneeling) shoot arrows at the Niobids to avenge

their mother Leto. It is thought that the many sculptures depicting this scene may have derived

from a frieze which decorated the throne of the colossal chryselephantine statue of Zeus made

by the Athenian sculptor Pheidias for the supreme god's temple at Olympia around 432 BC.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1887.7-21.1 (Sculpture 2200).

Unfortunately, the roundel is currently (2016) displayed in the shadow of a nearby statue. |

| |

The Death of the Niobids, gold relief by Antonio Gentili (1519-1609). Gold sheet on a background

plate of lapis lazuli, decorated with carnelians. From a series of six mythological scenes

made in Rome around 1600, after models by Guglielmo della Porta made 1552-1555.

Bode Museum, Berlin. Inv. No. 2911. |

|

The interior of the cave of the Monument of Thrasyllos, converted into the

church of Panagia Spiliotissa (Παναγία Σπηλιώτισσα, Virgin of the Cave).

Drawing by Simone Pomardi (1757-1830) for Edward Dodwell.

|

7. The chapel of Panagia Spiliotissa

Early travellers referred to this chapel simply as Panagia Spiliotissa (or Speliotissa), translated variously as Madonna, Virgin, Our Lady or Blessed Lady of the Cave or Grotto. It seems that at some point it was upgraded to Panagia Chrysospiliotissa (Παναγία Χρυσοσπηλιώτισσα, Virgin of the Golden Cave).

Dr. Richard Chandler (see gallery page 8, 12, 32 and 36) witnessed a mass in the chapel during his visit to Athens in 1765-1766:

"The Greeks have converted the cave into a chapel, which is called Panagia Spiliótissa, The Virgin of the Grotto. The sides of the rock within are covered with holy portraits. The door is rarely open, but I was once present at the celebration of mass, when it was lighted up with wax-candle, and filled with smoke of incense, with bearded priests, and a devout croud; the spectacle suiting the place, which is at once solemn and romantic."

Richard Chandler, Travels in Greece, or an account of a tour made at the expense of the Society of Dilettanti, Chapter 12, page 63. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1776. At the Internet Archive.

Edward Dodwell, who first visited Athens in 1801, described the interior:

"The cave seems to have been originally formed by nature, and to have been enlarged by art. It penetrates about thirty four feet under the rock, and its general breadth is twenty feet. The only antiquities that it contains are a few blocks of marble, a small columnar pedestal, perhaps for a tripod; and a fluted columnar altar, similar to those at Chaeronia. Here also is an ionic capital of small proportions and coarse workmanship, with some appropriate paintings of the Virgin of the Cave. It receives a dim and mysterious light, through two small apertures in the modern wall, by which a singular and picturesque effect is produced."

Edward Dodwell (1767-1832), Irish painter, travel writer and antiquarian, A classical and topographical tour through Greece, during the Years 1801, 1805, and 1806, Volume Ι, chapter X, page 300. Rodwell and Martin, London, 1819.

According to Dodwell's measurements, the depth of the cave is about 10.36 metres, and the general width 6.09 metres. This corresponds roughly to the measurements given by Dr. Giorgos Papathanassopoulos, former Director of the Acropolis, who gives a depth of 6.2 metres and a height of 6 metres. The stated width of 1.70 metres is either an error or refers to the width of the entrance.

See: Dr. G. Papathanassopoulos (Γιώργος Παπαθανασόπουλος), The Acropolis, a guide to the monuments and the new museum, page 11. Krene Editions, Athens, 2006.

Until some time before the beginning of the most recent restoration work a lamp was lit in the cave every evening. The eerie light from the lantern could be seen from some distance from the Acropolis.

Following the destruction of the chapel during the Turkish siege of 1826-1827, an new church was built in 1832. However this was later considered too small for requirements, and from 1846 funds were collected for the construction of a larger church. Building began in 1863, but not completed until 1892.

The grandiose Panagia Chrysospiliotissa (Ναός Παναγίας της Χρυσοσπηλιώτισσας) is at 62 Aiolou Street, in the centre of Athens, and is considered as one of the city's most important Greek Orthodox churches.

One of the supervising architects was Ernst Ziller (1837-1923), a German who became a Greek citizen and was responsible for several royal, municipal and private buildings, churches and railway stations in Greece, including the National Library of Greece, the Athens Academy, the National Archaeological Museum, as well as the renovation of the Panathenaic Stadium. He also designed the tomb of the millionaire archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann (see Acropolis gallery page 11). |

|

|

8. Νiccοlo da Martoni and the ship-sinking idol

For further information about the Gorgon Medusa, the aegis and their relationship to Athena, see Pergamon gallery 2, page 13 and the Gorgon Medusa page of the MFP People section.

Martoni, who kept a journal of his pilgrimage, arrived in Athens on 24th February 1395 and stayed for two days. He was shown around sights, including the Acropolis and the Temple of Olympian Zeus, which he was told was the Palace of Hadrian.

See:

James Morton Paton, Chapters on Mediaeval and Renaissance visitors to Greek lands, edited by L.A.P., Chapter 3 Niccolò da Martoni, pages 30-35. Gennadeion Monographs III. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton, New Jersey, 1951. PDF e-book at ascsa.edu.gr.

Crusader Athens III: Florentine Athens (1388 - 1456) by John L. Tomkinson. At anagnosis.gr. |

|

Bronze Gorgon's head,

probably from a shield of a statuette of Athena. From

the Athens Acropolis,

late 6th century BC.

National Archaeological

Museum, Athens.

Inv. No. 6510. |

|

9. Early visitors to Athens

The travellers, antiquarians, historians, amateur archaeologists and artists who

made drawings of and published information about this monument include:

John Montague, the fourth Earl of Sandwich (see drawing below),

Jacob Spon and George Wheler (see drawing below),

James Stuart and Nicholas Revett (see drawings above),

Doctor Richard Chandler,

Simone Pomardi for Edward Dodwell (see drawing above),

William Wilkins,

William Martin Leake,

Charles Robert Cockerell,

James Skene (see drawing above).

An architect employed by Lord Elgin also made drawings

of the monument at the beginning of the 19th century. |

|

| |

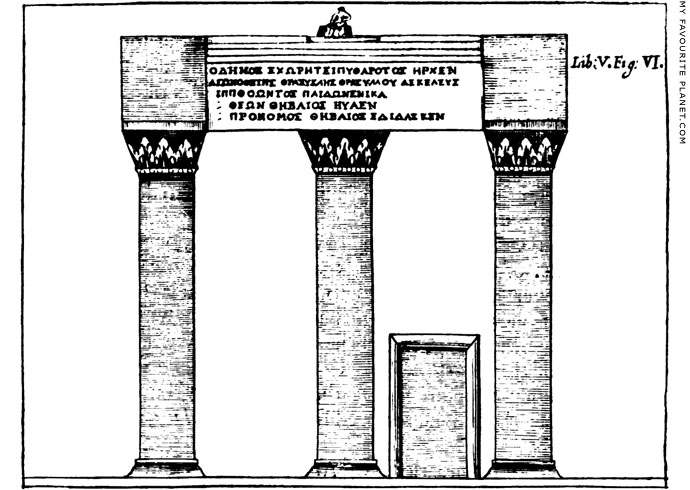

Drawing of the facade of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos by George Wheler (1650–1723).

Source: George Wheler, A journey into Greece in company of Dr Spon of Lyons, Book V,

fig. VI, page 368. Cademan, Kettlewell, and Churchill, London, 1682. At Googlebooks. |

| |

Detail of a drawing of the facade of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos

by John Montague, the fourth Earl of Sandwich (1718-1792).

|

Lord Sandwich and his companions made their voyage around the Mediterranean by ship 1738-1739, stopping at several Greek ports and islands. They spent spent two weeks in Athens, staying at the house of Niccolo Logotheti, the British consul. Although his visit was over a decade before that of Stuart and Revett, the journal of his voyage was first published sixty years later in 1799,

seven years after his death. The publication was perhaps spurred by the public interest in works meanwhile published or planned by other travellers.

Sandwich himself had been involved with the Society of the Dilettanti from its earliest years, became a member in 1740 after making his tour (a condition of membership), and was a subscriber to the first volume of Stuart and Revett's The Antiquities of Athens.

The journal appears heavily edited, with attention focused mainly on his own knowledge of classical literature, and little mention of the circumstances or conditions during the journey itself. The result is very sketchy.

Although the travellers employed the accomplished Swiss painter Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702-1789) to capture views and antiquities on their journey, the few illustrations in the book - inaccurate and poorly executed - appear to be by Sandwich himself. Part of a letter he wrote on his return to England in 1739 is quoted in the biography prefacing the journal. Apparently referring to himself in the third person, he writes:

"He copied above 50 Greek inscriptions never before made public; and took, himself, plans and drafts of the pyramids, and all the antient buildings." (page iii)

Sandwich does not name his travelling companions, who were: William Ponsonby, 2nd Earl of Bessborough (1704-1793), James Nelthorpe (circa 1719-1767), a Leeds landowner, and John Mackye (1707-1797), a Scotsman "of Palgowan, Kirkcudbright" who later became a Member of Parliament, and changed his name to John Ross-Mackye in 1755 on marrying the daughter and co-heiress of the thirteenth Lord Ross. They met Liotard either in Rome or Naples, and invited him to join them on their expedition, and to make studies of scenery, antiquities, locals in traditional costumes, etc. Although at some point Liotard made portraits of his fellow travellers, he remained in Constantinople while the others continued on their voyage, which may explain why no such studies were published.

John, Earl of Sandwich, A voyage performed by the late Earl of Sandwich round the Mediterranean in the years 1738 and 1739, edited by John Cooke. Engraving opposite page 58. Cadell and Davies, London, 1799. At googlebooks.

10. The restoration of the Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos

Of the four restoration plans submitted by the scientific committee for research, the most low-key intervention was accepted: 84 stones, rather than 106, are to be reassembled, 17 of which form part of the stepped base, 27 are extant ancient blocks to be returned to the site from the National Archaeological Museum, and 40 new blocks.

No time schedule was announced at the time, but work was continuing in late 2015.

See: Old landmark on the southern slope of the Acropolis is to get a facelift,

newspaper article by Iota Sykka, Ekathimerini (archive), 22 February 2003.

11. Julien-David Le Roy

Julien David Le Roy (1724-1803), French architect and archaeologist, son of Julien Le Roy, a clockmaker to the royal court in Paris. After winning le Grand prix d’architecture in 1750, Le Roy spent three years in Rome 1751–1754. In 1754 he sailed from Venice to Constantinople and obtained the necessary papers to continue through the Cyclades, including Delos, to Athens, at which he arrived on 1 February 1755. After measuring and drawing several of the ancient monuments of Athens, he returned to Paris in 1755, via Corinth and Sparta where he also made drawings.

Although he visited Greece after Stuart and Revett, he was the first to publish a detailed, illustrated book on the Athenian ruins, Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce, which appeared in 1758. Stuart, meanwhile was still working on his The Antiquities of Athens, the first volume of which was not published until 1762, and the final fourth volume appeared in 1816, 28 years after his death (see Acropolis gallery page 12). Stuart, understandably upset that Le Roy had managed to publish before him, strongly criticized the Frenchman for inaccuracies in his work.

Julien-David Le Roy, Les ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce. Paris, 1758. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

|

|

| |

The Choragic Monument of Thrasyllos viewed from the Theatre of Dionysos, August 2013. |

Photos, illustrations, maps and articles: © David John,

except where otherwise specified.

Additional photos: © Konstanze Gundudis

All photos and articles are copyright protected.

Images and materials by other authors

have been attributed where applicable.

Please do not use these photos or articles without permission.

If you are interested in using any of the photos for your website,

project or publication, please get in contact.

Higher resolution versions are available on request.

My Favourite Planet makes great efforts to provide comprehensive and accurate information across this website. However, we can take no responsibility for inaccuracies or changes made by providers of services mentioned on these pages. |

|

| |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|