|

|

|

| My Favourite Planet > English >

People > Ancient Greek artists> Architects |

| MFP People |

Ancient Greek artists – page 13 |

|

Page 13 of 14 |

|

|

| |

| Architects |

| |

"... so many of our architects come to Rome from Greece."

The names of a small number of ancient Greek architects and engineers have survived from the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic periods, as well as a handful who worked during the Roman period. In the early second century AD Emperor Trajan acknowledged the importance of Greek architects to the Romans.

Pliny the Younger (circa 61-113 AD, nephew of the writer Pliny the Elder) was the imperial governor of the Roman province of Bithynia and Pontus in northern Anatolia (Asia Minor; today northern Turkey). In a letter to Trajan he wrote of the problems local people in the Greek cities of Nicaea and Claudiopolis were having attempting to complete public building projects such as theatres, baths and gymnasia, and begged the emperor to send him an architect. Trajan sent the following reply:

"Trajan to Pliny.

You will be best able to judge and determine what ought to be done at the present time in the matter of the theatre which the people of Nicaea have begun to build. It will be enough for me to be informed of the plan you adopt. Do not trouble, moreover, to call on the private individuals to build the portions they promised until the theatre is erected, for they made those promises for the sake of having a theatre. All the Greek peoples have a passion for gymnasia, and so perhaps the people of Nicaea have set about building one on a rather lavish scale, but they must be content to cut their coat according to their cloth.

You again must decide on what advice to give to the people of Claudiopolis in the matter of the bath which, as you say, they have begun to build in a rather unsuitable site. There must be plenty of architects to advise you, for there is no province which is without some men of experience and skill in that profession, and remember again that it does not save time to send one from Rome, when so many of our architects come to Rome from Greece."

Pliny the Younger, Letters, Book 10, Letter 40 (Trajan's reply to Pliny's letter, No. 39). Translated by John Benjamin Firth. Walter Scott, London, 1900. At attalus.org. |

|

|

| |

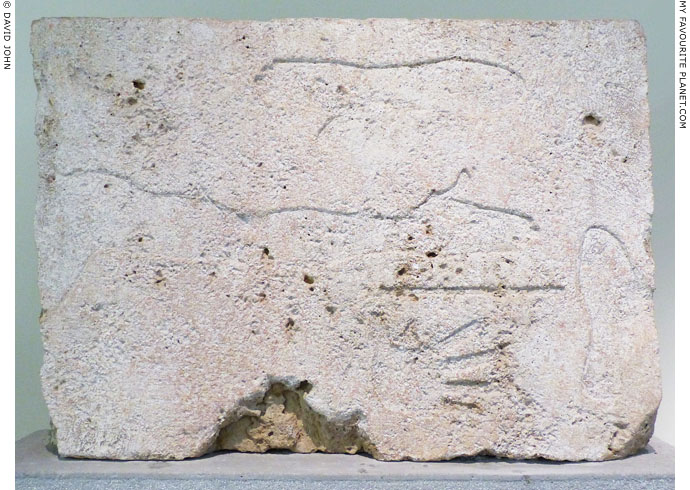

A stone plaque engraved with standard measurements. Metrical units are

given in half an orgyia (span) of the open arms: the pechys (cubit) = 48.7 cm,

spithame (open palm) = 24.2 cm, and two standards of the foot, 30.2 cm and

32.2 cm. The latter, in form of a rule, was used as a calculation of the cubit,

the palm and the span.

4th century BC. Found built into a chapel on the island of Salamis.

Piraeus Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 5352.

A similar relief with standard measurements (probably

a dedication) is now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. |

| |

Agamedes and Trophonios

Ἀγαμήδης και Τροφώνιος

Legendary or mythical architects fron Boeotia.

The brothers Agamedes and Trophonios, sons of Erginos (Ἐργῖνος), are mentioned by ancient authors as the architects of the first temple of Apollo at Delphi and a treasury for Hyrieus (Ὑριεὺς), king of Hyria in Boeotia, or in another version for King Augeas (Αὐγέας) at Elis.

While the earliest Delphic temple is thought to have been built around the 7th century BC, most of the stories concerning these brothers belong to the realms of legend or myth, and the timeless age of heroes such as Herakles. One of the tales concerning their deaths is similar to that of the Argive heroes Kleobis and Biton (see below). As in many cases in ancient Greek and lore (for example Daidalos), historical artists and architects may have been confounded with other legendary or mythological figures, or divine beings were credited with creating monuments. Agamedes also seems to have been confused with the mythical figure of the same name, a son of Stymphalos (Στύμφηλος) and great grandson of Arkas of Arcadia.

Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 9) related the legendary history of Minyan Orchomenos (Ὀρχομενὸν Μινυήιον) in Boeotia, central Greece, and how one of the city's kings, the aged Erginos (Ἐργῖνος), became father to Agamedes and Trophonios. The travel writer admitted to believing the tale that Trophonios was actually the son of Apollo, and was the divine hero or daimon whose oracular cult was centred on the Cave of Trophonios at Lebadeia (Λεβαδείᾳ or Λιβαδειά, today Livadia) in Boeotia. After building the temple of Apollo at Delphi, they constructed the treasury for Hyrieus which they then proceeded to rob. Agamedes was caught in a trap set by Hyrieus, and Trophonios, unable to free his brother, cut off his head but was then himself swallowed by the earth.

"Trophonius is said to have been a son of Apollo, not of Erginus. This I am inclined to believe, as does everyone who has gone to Trophonius to inquire of his oracle. They say that these, when they grew up, proved clever at building sanctuaries for the gods and palaces for men. For they built the temple for Apollo at Delphi and the treasury for Hyrieus. One of the stones in it they made so that they could take it away from the outside. So they kept on removing something from the store. Hyrieus was dumbfounded when he saw keys and seals untampered with, while the treasure kept on getting less.

So he set over the vessels, in which were his silver and gold, snares or other contrivance, to arrest any who should enter and lay hands on the treasure. Agamedes entered and was kept fast in the trap, but Trophonius cut off his head, lest when day came his brother should be tortured, and he himself be informed of as being concerned in the crime.

The earth opened and swallowed up Trophonius at the point in the grove at Lebadeia where is what is called the pit of Agamedes, with a slab beside it."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 37, sections 5-7. At Perseus Digital Library.

In another version of the tales by the historian Charax of Pergamon, quoted by a scholiast (commentator) on Aristophanes' Clouds (line 508), Agamedes, prince of Stymphalos, was the father of Trophonius, who was illegitimate, and Kerkyon (Κερκυον). Agamedes and Trophonius, famed for their skill, built the temple of Apollo at Delphi. They also constructed a golden treasury for King Augeas (Αὐγέας) at Elis, but included a secret entrance in order to rob it. Daidalos, who was staying with Augeas, advised him to set a traps for the robbers, in one of which Agamades was caught. This version, "the story of Trophonios and Agamedes and Augeas" is also briefly referred to in a fragment of The Telegony, a poem of the Trojan cycle by Eugammon of Cyrene (around 568 BC).

Pausanias also wrote that Agamedes and Trophonios were said to have built a wooden temple of Poseidon Hippios (Ποσειδων Ἱππιος, Horse Poseidon) near Mantineia in Arcadia (central Peloponnese), at the foot of Mount Alesion (Ἀλήσιον). Emperor Hadrian later built a new temple around the ancient construction.

"Originally, they say, this sanctuary was built for Poseidon by Agamedes and Trophonius, who worked oak logs and fitted them together."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 10, sections 2-3. At Perseus Digital Library.

He also wrote that at Thebes they were reputed to have built a house for the exiled Amphitryon (Ἀμφιτρύων), son of king Alcaeus of Tiryns in Argolis:

"On the left of the gate named Electran are the ruins of a house where they say Amphitryon came to live when exiled from Tiryns because of the death of Electryon; and the chamber of Alcmena is still plainly to be seen among the ruins. They say that it was built for Amphitryon by Trophonius and Agamedes, and that on it was written the following inscription:

'When Amphitryon was about to bring hither his bride

Alcmena, he chose this as a chamber for himself.

Anchasian Trophonius and Agamedes made it.'

Such was the inscription that the Thebans say was written here."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 9, chapter 11, sections 1-2. At Perseus Digital Library.

In the Homeric hymn to Pythian Apollo, the god is depicted planning the stone temple in Delphi with the brothers:

"When he had said this, Phoebus Apollo laid out all the foundations throughout, wide and very long; and upon these the sons of Erginus, Trophonius and Agamedes, dear to the deathless gods, laid a footing of stone. And the countless tribes of men built the whole temple of wrought stones, to be sung of for ever."

Homeric hymn to Pythian Apollo, lines 294-299. In: Hugh G. Evelyn-White (translator and editor), Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns, and Homerica.

Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. and William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1914. At Project Gutenberg.

According to tradition at Delphi, the temple by Agamedes and Trophonios was the fourth on the site, although Pausanias found it difficult to believe in the first three: the first was said to have been built of laurel branches from the Vale of Tempe, the second was made by bees from beeswax and feathers, and the third constructed of bronze by the god Hephaistos.

"The fourth temple was made by Trophonius and Agamedes; the tradition is that it was made of stone. It was burnt down in the archonship of Erxicleides at Athens, in the first year of the fifty-eighth Olympiad [548 BC], when Diognetus of Crotona was victorious. The modern temple was built for the god by the Amphictyons from the sacred treasures, and the architect was one Spintharus [Σπίνθαρος] of Corinth."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 10, chapter 5, section 13. At Perseus Digital Library.

In a letter of condolence once thought to have been written by Plutarch but now attributed to Pseudo-Plutarch, a story by the Theban poet Pindar is cited in which, after building the temple at Delphi, Apollo rewards Agamedes and Trophonios by allowing them to die in their sleep after seven days of celebrating. The author likened their fate to the legendary death of Kleobis and Biton.

"First I shall relate for you the tale of Cleobis and Biton, the Argive youths. They say that their mother was priestess of Hera, and when the time had come for her to go up to the temple, and the mules that always drew her wagon were late in arriving, and the hour was pressing, these young men put themselves to the wagon and drew their mother to the temple; and she, overjoyed at the devotion of her sons, prayed that the best boon that man can receive be given them by the goddess. They then lay down to sleep and never arose again, the goddess granting them death as a reward for their devotion.

Of Agamedes and Trophonius, Pindar says that after building the temple at Delphi they asked Apollo for a reward, and he promised them to make payment on the seventh day, bidding them in the meantime to eat, drink, and be merry. They did what was commanded, and on the evening of the seventh day lay down to sleep and their life came to an end."

Plutarch, A letter of condolence to Apollonius (Consolatio ad Apollonium), 109A, pages 144-145. In: Plutarch's Moralia Volume 2 (of 16). In Greek with an English translation by Frank Cole Babbit, pages 105-211. Loeb Classical Library edition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. and William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1962.

More or less the same story was told by Cicero in Tusculan Disputations (Tusculanae Quaestiones), although in his version the architects died after three days.

Cicero's Tusculan disputations, Book 1, section 47, pages 60-61. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge. Harper & Brothers, New York, 1888. At the Internet Archve.

The tale also appears in a fragment attributed to Plutarch:

"Trophonius and Agamedes, having built a temple at Delphi, asked Apollo for their reward. He replied that he would give it them six days later; and six days later they died. Again, Cydippe, the mother of Cleobis and Biton, prayed to Hera to give her sons whatever might be her finest gift, because they had harnessed themselves and drawn their mother to the goddess's temple; they immediately passed away. Someone has composed an epigram on them as follows:

'Here lie Biton and Cleobis, who placed a yoke on their own shoulders and drew their mother to the shrine of Hera. The people envied her for having such fine children for her sons, and she in her joy prayed to the goddess that her sons might be allotted the best of fortunes, since they had done this honour to their mother. And thereupon they laid them down to sleep and departed life in their youth, showing this to be the best and most blessed thing there is.'"

Plutarch, from the work A woman, too, should be educated, fragment 133; Stobaeus, iv. 52. 43 (v, p. 1085 Hense). In: Plutarch's Moralia Volume 15: Fragments. In Greek with an English translation by F. H. Sandbach, pages 246-249. Loeb Classical Library edition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. and William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1987. At the Internet Archve. |

|

|

| |

Chersiphron

Χερσίφρων (Chersiphron of Gnosus; Latin, Chersiphrone Gnosio)

From Knossos, Crete, 6th century BC

In some English editions of Vitruvius, his name appears as "Ctesiphon". This is due to an error which appeared in Joseph Gwilt's 1826 translation. In Latin editions the name is Chersiphron.

According to Strabo, Vitruvius and Pliny the Elder, Chersiphron was the principal architect of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (the Artemision, Ἀρτεμίσιον), with his son Metagenes (Μεταγένης). He is thought to to have designed the Archaic temple, on which construction began around 550 BC, following the destruction of the earlier temple in the 7th century BC, probably during Cimmerian invasions and/or by flooding of the site. It was partly financed by King Croesus of Lydia (Κροῖσος, ruled circa 560-547 BC), who paid for most of the columns and donated a number of golden cows (Herodotus, Histories, Book 1, chapter 92).

"For in four places only are the temples embellished with work in marble, and from that circumstance the places are very celebrated, and their excellence and admirable contrivance is pleasing to the gods themselves. The first is the temple of Diana [Artemis] at Ephesus, of the Ionic order, built by Chersiphron of Gnosus, and his son Metagenes, afterwards completed by Demetrius, a priest of Diana, and Paeonius the Ephesian.

Vitruvius, The ten books on architecture, Book 7, Introduction, section 16. At LacusCurtius.

Vitruvius also mentioned that Chersiphron and Metagenes wrote a treatise on the Ionic order in the temple:

"... Silenus published a book on the proportions of Doric structures; Theodorus, on the Doric temple of Juno [Hera] which is in Samos; Chersiphron and Metagenes, on the Ionic temple at Ephesus which is Diana's..."

Vitruvius, The ten books on architecture, Book 7, Introduction, section 12. At LacusCurtius.

"Chersiphron was the first architect of the temple of Diana; another afterwards enlarged it, but when Herostratus set fire to it, the citizens constructed one more magnificent."

Strabo, Geography, Book 14, chapter 1, sections 22-23. At Perseus Digital Library.

Chersiphron's temple was burnt down by Herostratus (Ἡρόστρατός) in July 356 BC, and was replaced by yet another, grander temple, one of the largest in the Graeco-Roman world, which became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The designer, according to Gaius Julius Solinus (Polyhistor, 40, 2) was Deinokrates of Rhodes (Δεινοκράτης ὁ Ῥόδιος), referred to by Strabo as Cheirokrates (Geography, Book 14, chapter 1, section 23).

Chersiphron is also named as the principal architect of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus by Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book 7, chapter 38, and Book 36, chapter 21). |

|

|

| |

Deinokrates (or Stasikrates)

Δεινοκράτης

Sculptor, architect and city planner, from Macedonia or Rhodes

4th - 3rd century BC

Thought to be the same artist mentioned but named differently by ancient authors:

Cheirokrates; Deinokrates or Dinocrates, Deinokrates of Rhodes; Dinochares; Diocles of Rhegium ; Stasikrates or Stasicrates; Timochares. |

|

This article is currently being rewritten.

A longer article about Deinokrates

will be appearing on a separate page. |

|

|

| |

Hermodoros of Salamis

‛Ερμόδωρος ο Σαλαμίνιος (Latin, Hermodoro Salaminio)

From Salamis (Σαλαμίς), Cyprus

Thought to have been working in Rome around 146-102 BC.

The evidence for the life and work of Hermodoros is even thinner than that for many other ancient Greek artists. The key reference is at least second hand, being a sentence attributed to the Roman biographer Cornelius Nepos (circa 110-25 BC) quoted by the 6th century AD Byzantine grammarian Priscian (Priscianus Caesariensis):

"Nepos: aedis Martis est in Circo Flaminio architectata ab Hermodoro Salaminio."

"Nepos: The temple of Mars is in the Circus of Flaminius, the architect Hermodoros of Salamis."

Priscian, Institutiones grammaticae (Foundations of grammar), completed around 526 AD.

See: Martin Hertz’s edition of Heinrich Keil, Grammatici Latini, Volume II, Prisciani, Institutiones grammaticae, Libri I-XII, Liber VIII, 17, page 383. B. G. Teubner, Leipzig, 1855. At the Internet Archive.

This temple of Mars, god of war, stood at the northwest end of the Circus of Flaminius, on the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) in Rome. Consul Decimus Junius Brutus Callaecus (or Callaicus) vowed to build a temple dedicated to Mars in 138 BC, and construction began after 135 BC, financed with booty from his military campaign in Hispania. It was dedicated in 132 BC during Callaecus' triumph. Its remains lie beneath the church of San Salvatore in Campo. Pliny the Elder (Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4) mentioned a colossal marble statue of seated Mars in the temple (see Skopas).

When defining the form of peripteral temples, the architect Vitruvius provided as an example the temple of Jupiter Stator in the Portico of Metellus (later known as the Porticus Octaviae) in Rome, designed by "Hermodorus":

"A temple will be peripteral that has six columns in front and six in the rear, with eleven on each side including the corner columns. Let the columns be so placed as to leave a space, the width of an intercolumniation, all round between the walls and the rows of columns on the outside, thus forming a walk round the cella of the temple, as in the cases of the temple of Jupiter Stator by Hermodorus in the Portico of Metellus, and the Marian temple of Honour and Valour constructed by Mucius, which has no portico in the rear."

Vitruvius, The ten books on architecture, Book 3, chapter 2, section 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

The name of the architect in manuscripts of Vitruvius' work has been read differently by various scholars, and in early printed editions it appears as "Hermodi" (Hermodius or Hermodus). The emendation or "correction" to Hermodorus, made by the French classical scholar Adrianus Turnebus (Adrien Turnèbe or Tournebeuf, 1512-1565), now appears to be generally accepted, perhaps partly on the strength of the sentence in Priscian and the mention of a Hermodorus by Cicero (see below).

The Porticus Octaviae, in the area of the Circus of Flaminius, on the southern side of the Campus Martius, was originally named the Portico of Metellus (Porticus Metelli), and was built in 146 BC by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus (circa 210-115 BC), following his victories in the Macedonian Wars (see the photos and information on the Alexander the Great page). Probably also financed by war booty, its colonnades surrounded the temples of Jupiter Stator and Juno Regina ("the two temples without inscriptions"). Since Vitruvius was using the temple of Jupiter as an example of a peripteral temple (probably because it would have been familiar to his Roman readers), he did not mention who designed the temple of Juno or the portico itself.

At some unknown time statues of Jupiter and Juno by Polykles and Dionysios were placed in the temples (Pliny, Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4; see Polykles), but we are not told when they were made, or whether they were created in Rome or brought from Greece. The Temple of Jupiter also contained an ivory statue of Jupiter by Pasiteles (Natural History, Book 36, chapter 4).

Writing on oratory Cicero (106-43 BC) asked a "what if" question, inviting his readers to imagine the famous orator Marcus Antonius (83-30 BC) speaking as the defence lawyer for the famous dock builder Hermodorus. This does not necessarily mean that the two were contemporaries.

"Nor, if, as is said, Philo, the famous architect, who built an arsenal for the Athenians, gave that people an eloquent account of his work, is it to be imagined that his eloquence proceeded from the art of the architect, but from that of the orator. Or, if our friend Marcus Antonius had had to speak for Hermodorus on the subject of dock-building, he would have spoken, when he had learned the case from Hermodorus, with elegance and copiousness, drawn from an art quite unconnected with dock-building."

John Selby Watson (translator and editor), Cicero on oratory and orators, De Oratore, or, On the character of the orator, Book 1, Chapter IV, pages 21-22. Harper and Brothers, New York, 1860. At the Internet Archive.

From these three mentions of one or more men named Hermodorus, two as architect and one as dock builder, it has been suggested that a Greek Cypriot architect named Hermodoros of Salamis was working in Rome in the second half of the second century BC, and was apparently kept busy. As well as the temple of Mars and the Jupiter Stator he may have also designed the adjacent temple of Juno Regina and the surrounding portico. As a dock builder he may have designed the Navalia, a port and arsenals on the left bank of the river Tiber. It has also been suggested that he may have designed the circular Temple of Hercules Invictus (Hercules Victor) at the Forum Boarium in Rome (see below). |

|

|

| |

The circular Temple of Hercules Victor, Rome. 2nd century BC.

|

The Temple of Hercules Invictus (Temple of Hercules Victor; Italian, Tempio di Ercole Vincitore) is on the west side of the Piazza della Bocca della Verita, across the road from the Arch of Janus and the Arcus Argentariorum, all of which stand within the site of the Forum Boarium, the ancient cattle market. It was formerly believed to be the Temple of Vesta until the discovery of the base of a cult statue with a dedicatory inscription to Hercules Olivarius, the patron god of the corporation of olearii (oil merchants).

It was founded in the second half of the 2nd century BC by either a Roman merchant or Lucius Mummius Achaicus, the politician and general who defeated the Achaean League and plundered and destroyed Corinth in 146 BC. The architect may have been Greek, perhaps Hermodoros of Salamis, who is thought to have been working in Rome during this period. 14.8 metres in diameter, the temple was built entirely of Pentelic marble (from Mount Pendeli, Athens), with a circular cella surrounded by a ring of 20 fluted Corinthian columns, 10.66 metres tall. It is the oldest surviving marble building in Rome. It was damaged in the 1st century AD, probably during the flood of 15 AD, and restored by Emperor Tiberius (reigned 14-37 AD) who replaced ten of the columns and capitals with white Luni marble. The original entablature and roof have not survived, and one of the columns at the back of the temple is missing.

Pliny the Elder mentioned famous paintings by the playwright Pacuvius in the Temple. Since he used the past tense, they may have been destroyed at the time of the damage to the temple.

"Next in celebrity were the paintings of the poet Pacuvius, in the Temple of Hercules, situated in the Cattle Market. He was a son of the sister of Ennius, and the fame of the art was enhanced at Rome by the success of the artist on the stage."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 35, chapter 7.

In a local version of the story of Herakles' eighth labour, the hero passed through Rome with the cattle he had stolen from Geryon. The monster Cacus took some of the cattle and hid them in a nearby cave. Herakles killed Cacus and retrieved the cattle, and to celebrate his victory sacrificed a number of bulls at or near the site of the Forum Boarium. The Great Altar (Ara Maximus) of Hercules Invictus is thought to have stood in the forum, perhaps in the precinct of the nearby church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, where a colossal gilded bronze statue of Hercules was discovered (Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Museums, Rome. Inv. No. MC 1265).

It is thought that there were two temples of Hercules at or around the Forum Boarium. The question of the location of the temple or temples of Hercules here, mentioned by ancient authors (Pliny, Servius, Macrobius), remains a matter of debate. One of the temples may have been the building demolished by Pope Sixtus IV, or at the nearby Circus Maximus.

This temple was converted into the church of Santo Stefano alle Carozze (Saint Stephen of the carriages) during the Middle Ages (before 1132), and rededicated to Santa Maria del Sole (Saint Mary of the Sun) in the 17th century. The spaces between the columns were closed by walls, some with windows, and a bell tower was added to the front of the roof. It was restored 1809-1810, during the Napoleonic occupation of Rome (1809-1814), by the architect Guiseppe Valadier (1762-1839) and the archaeologist and lawyer Carlo Fea (1753-1836). The later additions, such as the walls between the columns, were removed and the remains of original marble walls around the cella were repaired, partly with marble found around the site, as well as mortar and brick. During excavations carried out at the time of the restoration the original entrance was discovered.

The temple and the neighbouring Temple of Portunus (or Fortuna Virilis), the Roman god of harbours, are not open to the public, but may be visited with a guide or escort by making an appointment at least 24 hours in advance.

Information and reservations, Tel: 06 399 67700.

See www.archeoroma.beniculturali.it |

|

|

| |

Iktinos

Ικτίνος (Latin, Ictinus)

Architect and sculptor from Athens, mid 5th century BC

Iktinos and Kallikrates designed the Parthenon in Athens, built between 447 and 438 BC (Plutarch, Parallel lives, Pericles, chapter 13, section 4).

Vitruvius mentioned that he wrote a book about the Parthenon with a certain Carpion (Karpion, Καρπιον ?), otherwise unknown, (Ten Books on Architecture, Book 7, Introduction, section 12), and that he completed the Telesterion, the temple of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis, in the Doric style (section 16).

He was also the architect of the Temple of Apollo Epikourios (Επικούριος, the Helper) at Bassai, in the territory of Phigalia, Arcadia, in the Peloponnese. Built between 450 and 400 BC, the temple featured a Doric exterior, an Ionic interior, and the earliest known Corinthian column (according to Vitruvius, Book 4, chapter 1, invented by Kallimachos) at the rear of the cella. It is aligned north-south, rather than east-west usual for Greek temples, with its main entrance at the north end. This is thought to be due to the limited space on the mountainous terrain.

"Phigalia is surrounded by mountains, on the left by the mountain called Cotilius, while on the right is another, Mount Elaius, which acts as a shield to the city. The distance from the city to Mount Cotilius is about forty stades. On the mountain is a place called Bassae, and the temple of Apollo the Helper, which, including the roof, is of stone.

Of the temples in the Peloponnesus, this might be placed first after the one at Tegea for the beauty of its stone and for its symmetry. Apollo received his name from the help he gave in time of plague, just as the Athenians gave him the name of Averter of Evil [Alexikakos, see Kalamis] for turning the plague away from them.

It was at the time of the war between the Peloponnesians and the Athenians that he also saved the Phigalians, and at no other time; the evidence is that of the two surnames of Apollo, which have practically the same meaning, and also the fact that Ictinus, the architect of the temple at Phigalia, was a contemporary of Pericles, and built for the Athenians what is called the Parthenon."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 8, chapter 41, sections 7-9. At Perseus Digital Library.

The site was first excavated in 1811-1812 by Charles Robert Cockerell and his companions (see the Niobe page).

Pausanias (Book 8, chapter 30, sections 2-4) reported that the twelve foot high (4 metres) bronze cult statue of Apollo Epikourios was later taken from Bassai and set up in the sanctuary of Lycaean Zeus, in the agora of Megalopolis, founded around 370 BC (see Demeter and Persephone part 2).

The classical archaeologist and architectural historian William Bell Dinsmoor argued that three sculptures depicting the Niobids, now in Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen and the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome, may have decorated the south pediment of the Bassai temple, and that they may have been looted from there by the Romans. See the Niobe page. |

|

|

| |

The ruins of the Temple of Apollo Epikourios at Bassai (Βάσσαι), Arcadia, designed by Iktinos.

It has been suggested that the sculptor Paionios of Mende may have worked on the temple's

interior frieze, although this has been refuted. Surviving parts of the frieze, now in the British

Museum, depict an amazonomachy (a battle between Athenians and Amazons) and a

centauromachy (a battle between Lapiths and Centaurs).

Detail of a colour engraving after a drawing made in February 1806 by the Irish painter and

traveller Edward Dodwell (1767-1832). He visited Bassai six years before the temple's

surviving sculptures were taken off by Charles Robert Cockerell and his companions.

Source: Edward Dodwell, Views in Greece, page 115 (plate 28).

30 plates (unnumbered), with descriptions in French and English.

Rodwell and Martin, London, 1821. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

Dodwell described the temple and his visit in:

Edward Dodwell, A classical and topographical tour through Greece,

during the years 1801, 1805, and 1806, Volume 2 (of 2), pages 384-389.

Rodwell and Martin, London, 1819. At Heidelberg University Digital Library.

See also: Charles Robert Cockerell, The Temples of Jupiter Panhellenius

at Aegina, and of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae near Phigaleia in Arcadia.

John Weale, London, 1860. At Heidelberg University Digital Library. |

| |

Mnesikles

Μνησικλής

Sculptor and architect in Athens, 5th century BC

According to Plutarch, Mnesikles designed the Propylaia of the Athens Acropolis, and he may have also been the architect of the Erechtheion.

Plutarch, Parallel Lives, Pericles, 13.7-8.

Nothing is known of his life or other work. |

|

|

| |

Paionios of Ephesus

Παιώνιος (Paionios; Latin, Paeonius Ephesius)

Second half of the 4th century BC

According to Vitruvius, Paionios and Demetrius completed the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus begun by Chersiphron of Knossos and Metagenes, and the Temple of Apollo at Didyma (near Miletus) with Daphnis of Miletus.

"For in four places only are the temples embellished with work in marble, and from that circumstance the places are very celebrated, and their excellence and admirable contrivance is pleasing to the gods themselves. The first is the temple of Diana [Artemis] at Ephesus, of the Ionic order, built by Chersiphron of Gnosus, and his son Metagenes, afterwards completed by Demetrius, a priest of Diana, and Paeonius the Ephesian.

The second is the temple of Apollo at Miletus, also of the Ionic order, built by the above-named Paeonius, and Daphnis, the Milesian."

Vitruvius, The ten books on architecture,

Book 7, Introduction, section 16. English translation at Bill Thayer's LacusCurtius website, University of Chicago.

The most widely available translation by Morris Hicky Morgan (Harvard University Press, 1914) has "Paeonius the Milesian", although the Latin text states "Paeonius Ephesius". See: Vitruvius, de Architectura, Liber VII, Praefatio, section 16. At LacusCurtius.

For further discussion of the architects associated with the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, see the Deinokrates page (currently being rewritten).

Building of the enormous oracular temple of Apollo at Didyma began around 300 BC, and although much of the structure was complete by around 165 BC, work continued intermittently over the following centuries and it was never finished (see a brief history of the temple on the Medusa page). |

|

|

| |

Philon of Eleusis

Φίλων

Philon, son of Exekestides of Eleusis (Φίλωνος Ἐξηκεστίδου Ἐλευσινίου)

Athens, 4th century BC, around 350-305 BC

According to Vitruvius, Philon wrote a book (or books) on the proportions of temples and the naval arsenal at the port of Piraeus, and added a portico to the Telesterion, the temple of Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis.

Ten Books on Architecture, Book 7, Introduction, sections 12 and 16-17. At Project Gutenberg.

Philon is credited with the building of the Piraeus arsenal, known as the Skeuotheke (Σκευοθήκη), built for the storage of tackle and rigging for warships around 347-329 BC BC, during the administration of Lycurgus (Λυκοῦργος, Lykourgos; circa 390-324 BC).

He is mentioned by Cicero (106-43 BC) as "the famous architect, who built an arsenal for the Athenians" (Cicero on oratory and orators, Book 1, chapter 14, pages 21-22, at the Internet Archive).

Pliny the Elder mentions that "Philon, likewise, was highly esteemed for making the Arsenal at Athens, which was able to receive a thousand ships" (Pliny's Natural History, Book 7, chapter 37, at the Internet Archive). According to another version of the passage the number was 400 ("Philon Athenis armamentario CD navium", The natural history, Liber VII, xxxvii, 125, at LacusCurtius), and in other translations the arsenal is referred to as a basin or dockyard (The natural history, Book 7, chapter 38, at Perseus Digital Library).

Building accounts of the arsenal, Inscription IG II (2) 1668 (Epigraphical Museum, Athens, Inv. No. EM 12538), dated 347/346 BC, name "Philon, son of Exekestides of Eleusis" (Φίλωνος Ἐξηκεστίδου Ἐλευσινίου) and a certain "Euthydomos, son of Demetrios of Melite" as responsible for the building specifications (see photo below).

See:

Inscription of public nature (EM 12538) at nam.culture.gr.

Building work was suspended 340/339 BC because of the costs of the military campaign against Philip II of Macedon. The arsenal was probably destroyed in 86 BC by Lucius Cornelius Sulla during the Roman conquest of Athens. The remains of the building were rediscovered at the northwest corner of Zea Harbour, Piraeus during excavations in 1988-1989.

See:

Ernest Arthur Gardner, Ancient Athens, pages 557-559. Macmillan, 1907. At the Internet Archive.

David H. Conwell, Connecting a city to the sea: The history of the Athenian Long Walls, pages 150-151. Brill, Leiden, 2008.

The cella of the Telesterion at Eleusis had been enlarged in the Doric style by Iktinos in the mid 5th century BC. Around 317-307 BC Philon added a portico of twelve Doric columns, known as the Prostoon or Philonian Stoa, commissioned by Demetrius of Phaleron (Δημήτριος ὁ Φαληρεύς, circa 350-280 BC), who had been appointed to govern Athens by the Macedonian king Cassander. Epigraphic evidence (building accounts, Inscription IG II (2) 1673) indicates that Philon was not responsible for the original design or initial construction. The foundations, crepidoma and at least part of the colonnade were completed by a certain Athenodoros of Melite before Philon took over construction around 317 BC.

See: Paul T. Keyser, Georgia L. Irby-Massie, Encyclopedia of ancient natural scientists: The Greek tradition and its many heirs, "Philon of Eleusis". Routledge, 2008.

See also an inscription from Eleusis referring to the manufacture of bronze dowels for the columns of the Stoa of Philon in Demeter and Persephone part 1. |

|

|

| |

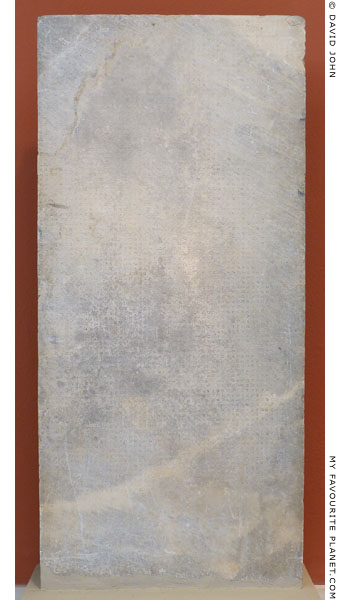

A marble stele inscribed with the specifications (syngraphai)

for the construction of the Piraeus Skeuotheke (arsenal),

entrusted to the architects Euthydomos and Philon of Eleusis.

347/346 BC.

Epigraphical Museum, Athens. Inv. No. EM 12538.

Inscription IG II² 1668. |

| |

Polykleitos

Πολύκλειτος

Mid-late 4th century BC

The name Polykleitos as an architect is mentioned only by Pausanias (Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 27, section 5).

Pausanias wrote that Polykleitos designed the tholos (θόλος, a circular building) and the great theatre in the Asklepieion at Epidauros. It has been suggested that Pausanias may have been referring to the sculptor Polykleitos the Younger, thought to have been the son of Polykleitos the Elder (Polykleitos of Argos). However, the theatre is thought to have been built around 340-320 BC (or later), which is considered too late for the dates assumed for the lifetimes of father and son.

"Near [the temple of Asklepios] has been built a circular building of white marble, called Tholos (Θόλος), which is worth seeing ... [a description of objects in the tholos] ...

The Epidaurians have a theatre within the sanctuary, in my opinion very well worth seeing. For while the Roman theatres are far superior to those anywhere else in their splendour, and the Arcadian theatre at Megalopolis is unequalled for size, what architect could seriously rival Polycleitus in symmetry and beauty? For it was Polycleitus who built both this theatre and the circular building."

Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 2, chapter 27, sections 3 and 5. At Perseus Digital Library.

Vitruvius wrote that "Theodorus Phocaeus" wrote a treatise on the tholos at Delphi, from which it has been assumed that he was the architect of the round building constructed around 40 years earlier than that at Epidauros (see Theodotos below). |

|

|

| |

Pytheos

Πυθέος (Pytheos of Priene, also referred to as Pythius or Pythis)

Sculptor, architect, author on architecture, 4th century BC

A contemporary of Bryaxis, Leochares, Skopas and Timotheos.

Pliny the Elder mentioned a "Pythis" as one of the artists who worked, along with Bryaxis, Leochares, Skopas and Timotheos, on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus (Μαυσωλεῖον τῆς Ἁλικαρνασσοῦ) around 350 BC. The tomb is named after the satrap (local governor in the Persian Empire) of Caria, Mausolus (Μαύσωλος, circa 377-351 BC), for whom it was built by his sister-wife Artemisia II of Caria (Ἀρτεμισία Β'), who died about two years after him. The enormous marble monument, which stood in the Carian capital Halicarnassus (see Herodotus and Panyassis), was elaborately decorated with numerous sculptures, and became known as one the Seven Wonders of the World (see drawing below).

According to Pliny, Pythis made a marble quadriga (four-horse chariot; Greek, τέθριππον, tethrippon) which stood on top of the pyramidal roof of the monument. He may have also designed the pyramid itself.

"Scopas had for rivals and contemporaries, Bryaxis, Timotheus, and Leochares, artists whom we are bound to mention together, from the fact that they worked together at the Mausoleum; such being the name of the tomb that was erected by his wife Artemisia in honour of Mausolus, a petty king of Caria, who died in the second year of the hundred and seventh Olympiad [351 BC]. It was through the exertions of these artists more particularly, that this work came to be reckoned one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

The circumference of this building is, in all, four hundred and forty feet, and the breadth from north to south sixty-three, the two fronts being not so wide in extent. It is twenty-five cubits in height, and is surrounded with six-and-thirty columns, the outer circumference being known as the 'Pteron'. The east side was sculptured by Scopas, the north by Bryaxis, the south by Timotheus, and the west by Leochares.

But, before their task was completed, Queen Artemisia died. They did not leave their work, however, until it was finished, considering that it was at once a memorial of their own fame and of the sculptor's art: and, to this day even, it is undecided which of them has excelled.

A fifth artist also took part in the work; for above the Pteron there is a pyramid erected, equal in height to the building below, and formed of four and twenty steps, which gradually taper upwards towards the summit; a platform, crowned with a representation of a [marble] four-horse chariot by Pythis. This addition makes the total height of the work one hundred and forty feet."

Pliny the Elder, Natural history, Book 36, chapter 4. Translated by John Bostock. Taylor and Francis, London, 1855. At Perseus Digital Library.

For some reason, in this translation the word "marble" has been omitted from the mention of the "four-horse chariot". In the Latin text it is described as "quadriga marmorea". The footnotes of this English edition point out that Pliny's description of the Mausoleum and the measurements are confused, and some modern alternative suggestions are offered.

Vitruvius mentioned Pytheos as an "ancient" architect who designed the Temple of Athena in Priene, Ionia, as author of a book about the temple of Athena at Priene, and co-author with Satyrus of a book on the Mausoleum. From the latter reference it is thought that Pytheos and Satyrus designed the Mausoleum. It is also thought that Pliny and Vitruvius were referring to the same person.

"But perhaps to the inexperienced it will seem a marvel that human nature can comprehend such a great number of studies and keep them in the memory. Still, the observation that all studies have a common bond of union and intercourse with one another, will lead to the belief that this can easily be realized. For a liberal education forms, as it were, a single body made up of these members. Those, therefore, who from tender years receive instruction in the various forms of learning, recognize the same stamp on all the arts, and an intercourse between all studies, and so they more readily comprehend them all.

This is what led one of the ancient architects, Pytheos, the celebrated builder of the temple of Minerva [Athena] at Priene, to say in his Commentaries that an architect ought to be able to accomplish much more in all the arts and sciences than the men who, by their own particular kinds of work and the practice of it, have brought each a single subject to the highest perfection. But this is in point of fact not realized."

Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 1, chapter 1, section 12. At Perseus Digital Library.

"It appears, then, that Pytheos made a mistake by not observing that the arts are each composed of two things, the actual work and the theory of it."

Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 1, chapter 1, section 15.

"Some of the ancient architects said that the Doric order ought not to be used for temples, because faults and incongruities were caused by the laws of its symmetry. Arcesius and Pytheos said so, as well as Hermogenes."

Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 4, chapter 3, section 1.

"(Afterwards Silenus published a book on the proportions of Doric structures ...) Pytheos, on the Ionic fane of Minerva which is at Priene ... on the Mausoleum, Satyrus and Pytheos who were favoured with the greatest and highest good fortune."

Vitruvius, Ten books on architecture, Book 7, Introduction, section 12.

The Temple of Athena Polias in Priene was partly financed by Alexander the Great, attested by an inscription on a marble wall block from the temple's ante, now in the British Museum.

In Latin manuscripts of Vitruvius' work the name of this architect is written four different ways: Phileos and Phiteus (both in Book 7, Introduction, section 12), Pythius (Book 1, chapter 1, sections 12 and 15), Pytheus (Book 4, chapter 3, section 1). However, scholars seem certain that all the references are to the same person, and although there is no absolute certainty which of these variants was the architect's real name, most have agreed on Pytheos (or the Latin Pytheus). Modern editions have been amended so that all mentions appear as Pytheos.

See: William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology, entry for "Phileus". John Murray, London, 1873 (?). At Perseus Digital Library. |

Part of the marble figure of a kneeling

Amazon from an Amazonomachy relief,

believed to have been part of the frieze

of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus.

Rhodes Archaeological Museum. |

| |

| |

| |

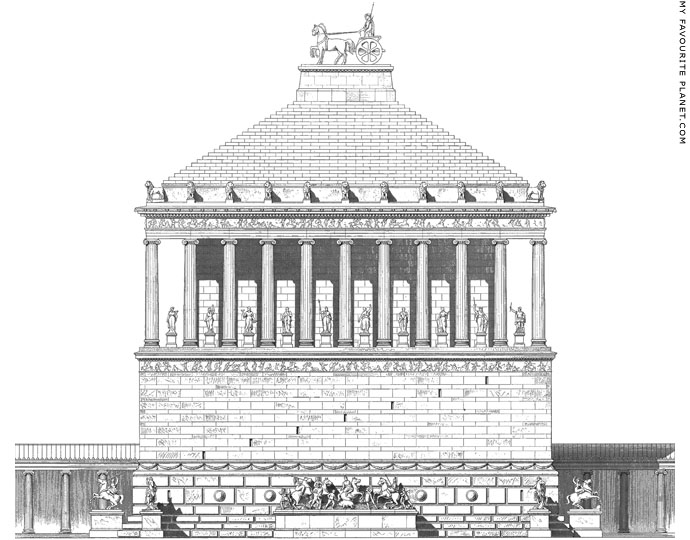

A reconstruction drawing of the south side of the

Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, built around 355-350 BC.

Drawing by the German architect and archaeologist Friedrich Adler (1827-1908).

Source: Atlas zur Zeitschrift für Bauwesen, Jahrgang 50, Blatt 3.

Ministerium der öffentlichen Arbeiten. Wilhelm Ernst und Sohn, Berlin, 1900. |

| |

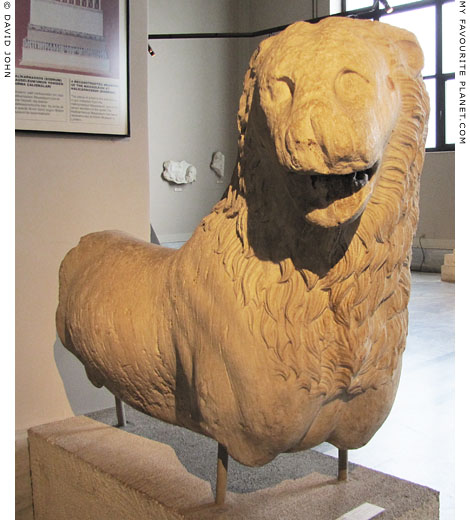

A marble statue of a lion from the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus,

Caria (Ancient Greek, Ἁλικαρνασσός; today Bodrum, Turkey).

Around 350 BC.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum. Inv. No. 313 T. Cat. Mendel 3. |

| |

Part of a marble statue of a lion from the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus.

Around 350 BC. Pentelic marble.

British Museum. Inv. No. GR 1857.12-20.242 (Sculpture 1077). |

| |

Skopas

Σκόπας (Latin, Scopas)

Sculptor and architect from Paros, active circa 395-350 BC.

Pausanias wrote that Skopas was the architect of the temple of Athena Alea in Tegea, Arcadia.

See Skopas under sculptors. |

|

|

| |

Sostratos of Knidos

Σώστρατος ὁ Κνίδος (or Σώστρατος Κνίδιος), son of Dexiphanes (Δεξιφάνες); Latin, Sostratus Cnidius

Late 4th - early 3rd century BC. From Knidos (Κνίδος), Caria (today, Yazıköy, Muğla Province, Turkey)

One of several ancient Greek artists named Sostratos. See Sostratos under Sculptors R - Z.

He is said to have been the designer of the Pharos Lighthouse of Alexandria in Egypt, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and a new type of monumental promenade at Knidos. He is also thought to have been an engineer, and to have acted as an ambassador for Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II, the first Hellenistic rulers of Egypt.

This article is currently being rewritten nad expanded. |

|

|

| |

Stasikrates (or Deinokrates)

Στασικράτης

Sculptor, architect and city planner, from Macedonia or Rhodes, 4th - 3rd century BC

Thought to be the same artist mentioned named differently by ancient authors:

Cheirokrates; Deinokrates or Dinocrates, Deinokrates of Rhodes; Dinochares; Diocles of Rhegium ; Stasikrates or Stasicrates; Timochares. |

|

This article is currently being rewritten.

A longer article about this artist

will be appearing on a separate page. |

|

|

| |

Theodotes

Θεόδοτος

Late 5th - early 4th century BC

A long inscription, found in 1885 to the east of the temple in the Asklepieion of Epidauros, details the costs of the Doric temple's construction (around 375 BC), and names some of the people who did the work. The entire project was superintended by the "architect Theodotes" (Θεόδοτος ἀρχιτέκτων), who received 353 drachms a year during the building, which took four years, eight months, and ten days. Contracts for various aspects of the work were made with artisans from different parts of Greece, including Corinth, Argos, Stymphalia and Crete.

A Thrasymedes (Thrasymedes of Paros who made the temple's cult statue?) undertook to execute the roof, wood covered with marble tiles, and the doors, made of ivory at a cost of 3070 drachms. A sculptor named Timotheos (perhaps Timotheos from Epidauros, contemporary of Skopas, Bryaxis and Leochares) is named as the maker of models after which various artists executed the figures in Pentelic marble on the pediments (gables) and those that stood on the roof (aktroteria). The sculptures of the western pediment are thought to have depicted a battle with the Amazons (Amazonomachy), and those on the eastern pediment a battle with the Centaurs (Centaurmachy).

Financial accounts for the temple: Inscription IG IV²,1 102 at The Packard Humanities Institute.

It has been suggested (not without challenges) that he may have been the architect "Theodorus the Phocian" (Latin, "Theodorus Phocaeus"), from Phocaea (Φώκαια, Phokaia, western Anatolia; modern-day Foça, Turkey), named by Vitruvius (On Architecture, Book 7, introduction, section 12, at Perseus Digital Library) as the author of a treatise on the tholos (θόλος, circular building) at Delphi. From this reference it is thought that Theodorus was the architect of the tholos, once a beautiful building, the remains of which stand in the sanctuary of Athena Pronaia (Athena "before the temple" [of Apollo]). It has been dated by stylistic features, particularly the sculptural decoration, to around 380-370 BC, although its function remains unknown. The surviving fragments of the sculptures have been described as "closely related" to those from the temple of Asklepios at Epidauros.

See, for example: Rosina Colonia, The Archaeological Museum of Delphi, page 307. John Latsis Public Benefit Foundation, Athens, 2006.

Pausanias (Book 2, chapter 27, sections 3 and 5) attributed the design of the tholos at Epidauros, built around 40 years later, to Polykleitos (see above). |

|

|

| Photos and articles © David John, except where otherwise specified. |

|

Visit the My Favourite Planet Group on Facebook.

Join the group, write a message or comment,

post photos and videos, start a discussion... |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

George Alvanos

rooms in

Kavala's historic Panagia District

Anthemiou 35,

Kavala, Greece

kavalarooms.gr

|

| |

Olive Garden Restaurant

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 109

kastellorizo.de

|

| |

Papoutsis

Travel Agency

Kastellorizo,

Greece

+30 22460 49 286

greeklodgings.gr

|

| |

|